Roughly one in two people with cardiovascular disease has no standard modifiable risk factors.

One local expert is leading the charge to find new, faster ways to identify cardiovascular disease risk in people with no standard risk factors.

“I spend a lot of time looking at people who are having heart attacks, who are looking up at me going, ‘why me?’ This is particularly [common in] women who really don’t think that coronary artery disease is going to be the thing that gets them… despite the fact that we’ve been very aware of coronary disease being one of the greatest killers of women and the biggest cause of impaired quality of life for over three decades.”

That’s how Professor Gemma Figtree, a cardiologist from the Royal North Shore Hospital and the University of Sydney, opened her plenary presentation on the unique landscape of cardiovascular health in women at the recent World Congress on Menopause.

One example was her friend and colleague Jennifer Tucker, who was diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome in her mid-30s, despite not having any of the risk factors traditionally associated with cardiovascular disease.

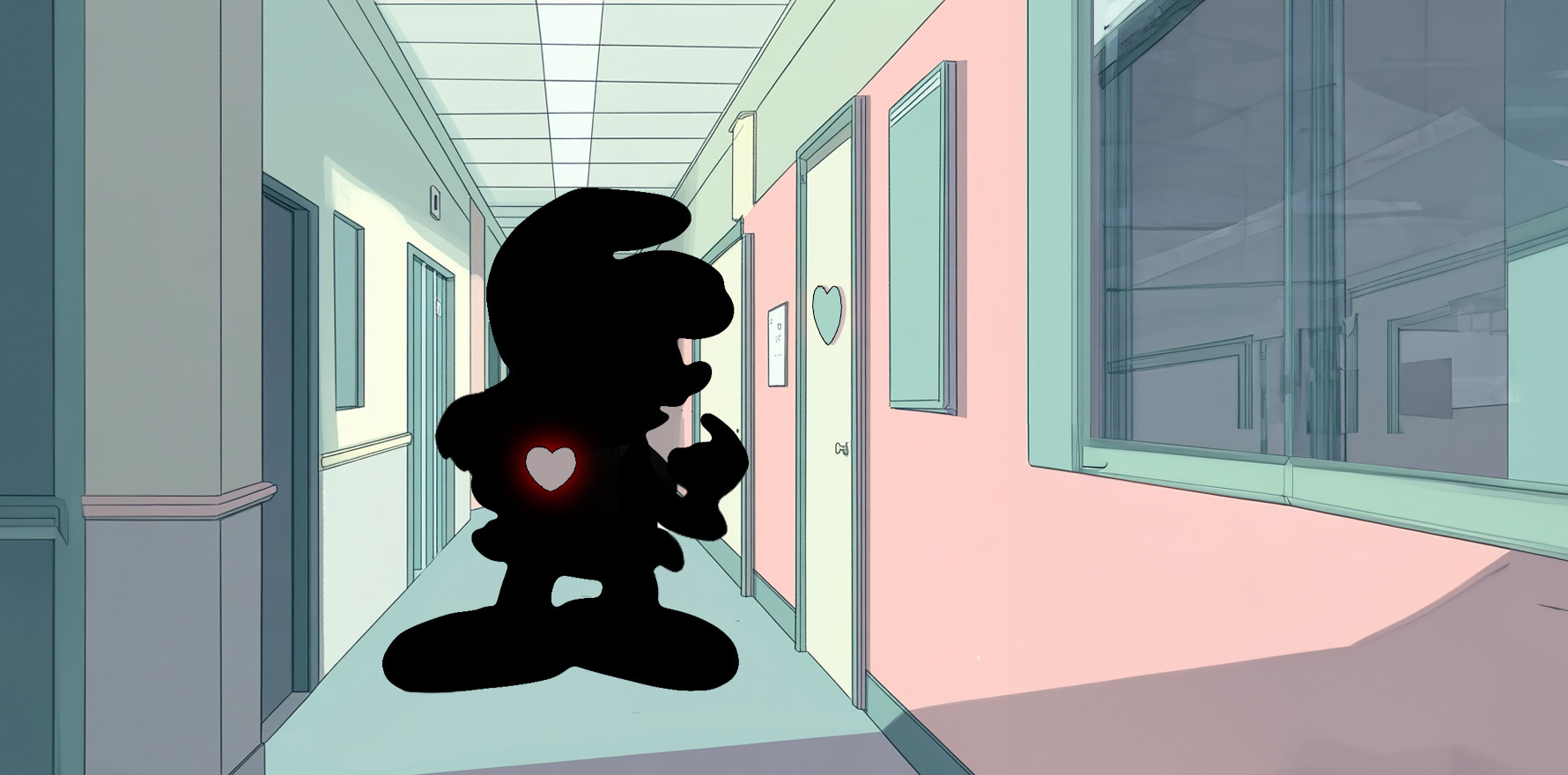

“We call her SmuRF-less – someone with no standard, modifiable risk factors,” Professor Figtree said.

Local data from the Royal North Shore Hospital suggests that up to 25% of first-time heart attack patients don’t have any SmuRFs – a figure that has increased over the last ten years.

“That’s probably because we’re getting better at treating traditional risk factors, and [now] we’re just seeing what’s always been there, which is a lot of stuff that’s not explained by the things we easily understand now,” said Professor Figtree.

In 2023 the Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium, which pooled over data from over 1.5 million patients from 112 cohort studies conducted in 34 countries, published similar findings: only 50-odd percent of cardiovascular disease occurred in people with at least one of five common, modifiable risk factors – BMI, blood pressure, non-HDL cholesterol, smoking or diabetes.

An international collaboration during the covid pandemic provided Professor Figtree and her collaborators the opportunity to explore the outcomes of SMuRF-less patients who experience a STEMI using data from the Swedish myocardial infarction registry, SWEDEHEART. The findings, published in The Lancet, left Professor Figtree “astonished”.

“If you had no risk factors, but you developed standard plaques [in your coronary arteries], you actually had a 50% higher chance of being dead within 30 days. And women with no risk factors have about a threefold [increase in] mortality at 30 days compared to men with traditional disk factors,” Professor Figtree said.

This led Professor Figtree to wonder how we can move beyond standard risk predictors, which assign people without the included risk factors as low risk, to better determine which people “actually have the ticking plaque time bomb”.

Professor Figtree compared the ideal approach to plaque screening to what happens in colon cancer, where the results of screening are staged based on an individual’s probability of having a polyp or a malignancy.

“[This approach] can help us then look for early disease – before it comes to the catastrophic endpoint. When it comes to plaque, we don’t want to wait for this [to happen]. We want to actually pick up the disease in the early stages,” said Professor Figtree.

Related

To do this, Professor Figtree has bought together a multidisciplinary team of national and international experts to form CAD Frontiers, which aims to fast-track the development and translation of technology that can use used to diagnose and treat coronary artery disease.

A key part of the approach is pairing CT coronary angiography with blood samples and clinical data – over a million data points per patient – to move beyond LDL and CRP levels to find more useful risk markers.

“If we can detect the plaque early, we could actually apply the same secondary prevention level of aggressiveness to individuals such that the plaque can really go into admission,” Professor Figtree told delegates.

“But in the meantime, we’ve also set up a SMuRFless clinic that’s got national and international engagement on how to best manage individuals who’ve had an event or got coronary artery disease despite [having] no standard modifiable risk factors,

“The first thing we do is actually confirm we’re not missing any of the major risk factors. We then make sure we do a comprehensive screening for other non-standard factors, and in women, we make sure to take into consideration some of those other potential contributors including [things] related to hormones and previous pregnancies.

“One of the things we think is really important in the SMuRFless population is obviously making sure that they get on traditional drugs that are a part of our secondary prevention guidelines, but also to use them to really advocate for the importance of [looking for] new biological mechanisms and drug target opportunities.

“We’ve [also] been working with the FDA to try and see how we can standardise CT measures to make sure we can reduce the study size number down from 15,000 over five years to 400 individuals over one year, which will incentivise the whole field to develop drugs that are focused on the plaque itself.

“Some people think we’re a little bit bonkers, but I think we have to be ambitious. We’re trying to shift the scientific and clinical paradigms for coronary disease … and I think it’s going to take quite a shift in mindset to achieve this.”

The IMS World Congress on Menopause was held in Melbourne from 19-22 October.