Actually AI is getting so good it’s becoming a serious temptation for newsrooms. Here’s how we use it (spoilers: hardly at all).

Healthcare is far from the only business boggling at the prospects of how artificial intelligence can help and/or harm it.

The prospect of assigning your donkey work to a piece of software and freeing up human intelligence for more fulfilling and, well, human work is tempting to everyone – except perhaps to very junior would-be employees for whom donkey work is the only way to get in the door.

But with the tech moving out of its outlandish novelty phase, you don’t have to be a big consumer of sci-fi to wonder where it will end.

Generally the creep of AI into the media has been a little subtler than using it to generate actual stories, though that is happening.

TMR has never used AI to generate a story – except this one, and this one, which are both about using AI to generate stories.

But we have long been fans of online transcription services, which are deploying smarter and smarter AI. Not only do they save us the countless hours reporters used to spend typing up their recorded interviews – all the while gagging at the sound of our own voices and stupid questions – while throwing out the occasional excellent mishearing for our amusement. They now also produce eerily accurate and articulate summaries of what transpired in the conversation.

As for images, The Australian Financial Review was widely pilloried last year for using these patently uncanny “photos” of Sam Kerr and Margot Robbie – causing one Redditor to comment that “Sam Kerr can count on one hand the amount of time her image has been AI generated. It’s 16 apparently.”

At least they were obvious. These days, a whole six months later, AI-generated art is more recognisable for the smooth and symmetrical perfection of its faces than for the disastrously mutated hands and supernumerous teeth of yesteryear (literally just last year).

Why are we banging on about this? Researchers at RMIT in this new paper undertook a literature review and surveyed 20 photo editors from 16 major media organisations in Europe, Australia and the US about their attitudes to AI in visual journalism.

The attitudes were largely positive, with adjectives like exciting, “fascinating”, “powerful”, “valuable”, “cool”, “creative” and “impressive” being deployed alongside “cheaper than humans” or words to that effect.

“However, even without discussing the tools in relation to journalism, participants expressed concerns, including how the underlying models were trained, the relationship of the generations to real-world depictions and how this could erode the credibility of camera-produced photographs, and the potential for AI-generated images to mislead or deceive.”

Within journalism, the concerns became “the intellectual property risks, the potential for mis/disinformation, and the effects on newsrooms and the people they employed”. As replacements for photojournalism, text-to-image generators were predictably “not welcome”.

Only six of the outlets had formal policies around generative AI images. “Five outlets had a policy barring staff from using AI to generate their own images (three of these only barred photorealistic generations, however). Four had a formal policy allowing the outlet to re-publish AI-generated images if the story is about AI-generated images. Two outlets had a policy that they would not use AI to replace wire service imagery. Two outlets had a policy to not use generative fill with photos. One had a policy that AI could be used for data visualisations. One had a policy that staff can use AI to illustrate stories about AI while another had a policy that forbade staff from using third-party generative visual AI services, such as Midjourney or DALL-E.”

The most common informal policy was only to use AI to illustrate stories about AI.

“Journalists’ cultural authority is predicated on their role as arbiters of what is true and what is false,” the authors write. “Generative visual AI interferes with this authority and can parallel misinformation in that, depending on the context, it can depict things that have not happened or people who do not exist.”

We take our “cultural authority” very seriously here at TMR.

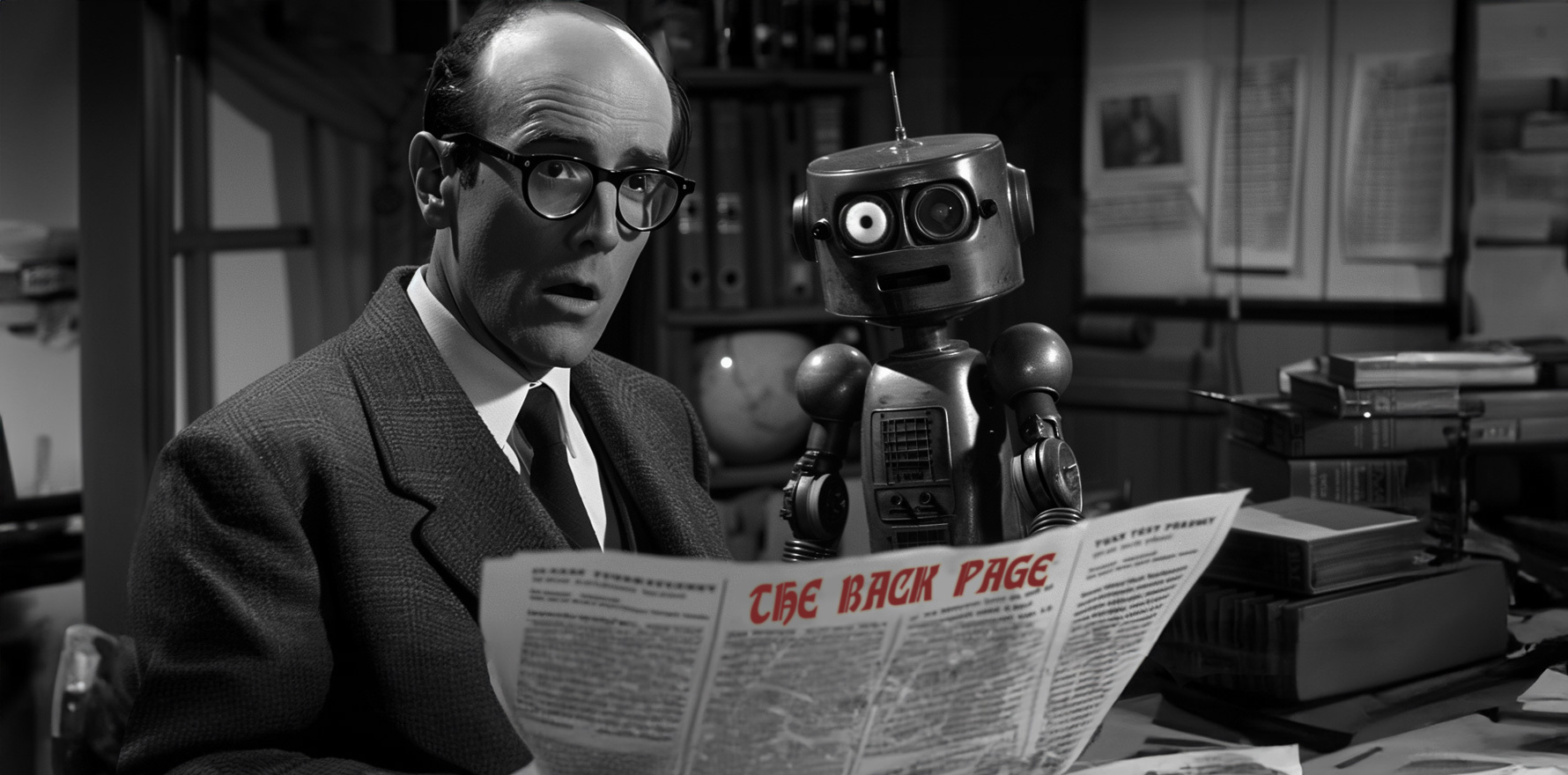

So, just so you know, we have an informal AI image policy along the lines mentioned above: we use generative art software almost exclusively to illustrate stories about AI (like this one). They usually feature a robot as a kind of visual avatar for the otherwise hard-to-illustrate concept of AI.

The other place we’ve used it is for humour purposes – we trust images like this run no risk of deceiving our readers into thinking they’re looking at a photo.

All our other pics are produced by an artist or are stock images from a subscription service more or less manipulated by an artist, or by a hack like your Back Page scribe, using a well-known photo-editing package. No artist or photographer has lost work through our use of AI.

That the programming of art- and language-generating AIs depends on mass plagiarism of human work, and that it replicates all the biases therein, are harder to disclaim.

All in all, it’s a curiosity that we hope will never become an essential. If serious pressure ever mounted to ban AI use entirely – which the respondents in this paper were not in favour of – we would miss it a little bit, but not that much.

Send seven-fingered story tips to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.