Male fertility has been barely an afterthought in most clinical trials of new medical therapies – until now.

When did you last read a study of a new drug or treatment which included any mention of – or even ruled out – potential adverse effects impacts on male fertility?

If you’ve been racking your brain for several minutes and still can’t think of one, you’re not alone. Surprisingly, given the inescapable biological fact that it requires both a male and female to contribute to a successful fertilisation event, male fertility is not even an afterthought in the vast majority of clinical trials of new medical therapies.

But this issue is currently on the radar, after the US Food and Drug Administration declined to approve oral JAK-1 inhibitor filgotinib for rheumatoid arthritis because of concerns about potential effects on sperm counts. Manufacturer Gilead then withdrew its application for approval not just in the US but in Australia as well[i], even before it had released the results of a study[ii] designed to investigate this exact issue (and which didn’t appear to show an effect compared to placebo[iii]).

Commenting on the filgotinib situation, an editorial in Lancet Rheumatology[iv] drew attention to what it called an “often-overlooked topic” of male infertility and rheumatologic drugs.

“Much of the available data on the effects of DMARDs on reproductive function are based on maternal exposures, and women are often counselled on the potential for adverse reproductive effects of these medications,” the editorial’s authors wrote. “Male infertility, by contrast, is often overlooked both when developing drugs and when prescribing them.”

That’s hardly news to Professor Rob McLachlan, director of Andrology Australia and expert on male reproductive health at Monash University. He said there are a significant number of new drugs – particularly in the oncology realm – that could potentially have effects on male reproductive health.

“But the evaluation they undergo for that particular topic is either cursory, only done in rodents or only done in a cursory way again because the reason you’re using them is very compelling,” Professor McLachlan said.

Regulatory authorities such as the Therapeutic Goods Administration and the US FDA generally don’t require companies to provide a standardised set of data on the reproductive impact of new treatments.

“There’s a need to get these agents to market and it’s not seen to be a priority,” he said. It’s further complicated by the difficulties in assessing male fertility in humans. “To what degree can you put your faith in animal models; to what extent does drop in sperm count predict outcomes?”

Difficult questions they may be, but ones that need to be answered, experts say, because the lack of knowledge could leave some men with potentially life-long infertility.

Mechanisms of harm

Cancer treatments are often designed to kill rapidly proliferating cells. The testes are a hotbed of proliferation, with a reproductively healthy male able to produce around

1000 sperm per heartbeat[v].

“There’s an increasing awareness that those well-established agents like alkylating agents – cyclophosphamide, for example – can cause spermatogenic dysfunction, and sometimes permanent dysfunction, depending on the dosage and whether or not there’s radiation therapy as well as chemotherapy,” said endocrinologist Professor Alvin Matsumoto, chief of gerontology at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle.

But there are also concerns about some of the newer anti-cancer drugs, such as the immune checkpoint inhibitors. In a recent study, Australian researchers reviewed the available pre-clinical and clinical trial data from 32 new oncology drugs, which were approved in Australia and/or the United States between 2014 and 2018, to see what information was available on reproductive function effects.

“Not one of those 32 drugs had any human data on reproductive effects, male or female,” said Dr Antoinette Anazodo, co-author on the study and director of adolescent and young adult cancer at Sydney Children’s and Prince of Wales Hospitals.

But when they looked at the preclinical animal study data on fertility – which was included for 23 of the drugs – only two drugs showed no adverse effects on fertility. Nine drugs caused male infertility in animals, and three caused female infertility.

This apparent gap in the data has since prompted them to look further into what human data is available on the impact of anti-cancer medications on male fertility.

“There’s almost no data with useful clinical implications available,” Dr Anazodo said.

There was a post-mortem study on seven males who had been treated with checkpoint inhibitors for cancer but had died. Six of them showed impaired spermatogenesis, but given they had a terminal illness which itself may have affected sperm function, that couldn’t be used as evidence. A case study of the anti-cancer drug dabrafenib suggested damaged spermatogenesis but a case study of high-dose vemurafenib found no evidence of gonadotoxicity.

“So, you can see limited human data and conflicting data,” Dr Anazodo said.

And it’s not just cancer treatments that can affect male fertility. As shown by the withdrawal of filgotinib, rheumatology treatments also have the potential to negative impact not only sperm count and function, but other aspects of reproductive health as well.

“Anything that has a sex steroid hormone effect or structure would be an obvious area,” said Dr Brad Anawalt, endocrinologist and Chief of Medicine at the University of Washington Medical Center. “We also need to think about the drugs that affect the immune system, which are commonly used in in the rheumatology kingdom.”

In the first, systemic glucocorticoids can suppress gonadotropins – the key hormones that regulate the production of sex hormones – and therefore impact sperm production. But the second – immunosuppressive medication – is less certain.

“There is a blood-testis barrier to prevent the immune system from having access, but we really don’t know what all these drugs that are affecting the various pathways in inflammation are doing,” Dr Anawalt said.

Even medical marijuana, which in some areas is used by rheumatology patients, can plausibly affect sperm production, he said. “That’s an example of a drug where you’d say ‘gosh, it would be great if we all went into these things with awareness of these potential side effects’.”

The challenge of finding fertility effects

It’s one thing to suspect potential impacts of a drug on male fertility. It’s a whole other thing to assess it. In this, women are actually easier to monitor for fertility effects.

“Women who are of reproductive age have a signal, which is their menstrual cycle, and about 95% of the time, if you’re having regular menses between 28 and 35 days, you’re ovulating,” Dr Anawalt said. “There’s no similar marker for men.”

The most obvious measurements would be of sperm function: counts and motility. But this requires getting sperm samples: “You’re asking men to do more than just submit a blood and urine sample,” Dr Anawalt said.

That can be even harder to do in the context of a clinical trial, which may involve thousands of men, many of whom might balk at the prospect of having to donate a sperm sample.

The other issue with assessing sperm function is that it can vary enormously over time in individual men, and across a population. Normal sperm concentrations range from around 20 million to 100 million per cc of seminal fluid, which means anywhere from 40 million to 300 million per ejaculation.

“If you’re going to sensitively study the effects of a drug on sperm counts, you actually need to have two or three sperm counts at baseline and then follow them on more than one occasion after they’ve taken the drug, so it’s considerably more time intensive,” Dr Anawalt said.

Even if sperm concentrations are low, that doesn’t necessarily signal infertility: a man can have a 90% drop in sperm count and still be able to conceive a child without medical assistance.

Sperm is also constantly being made, and the lifespan of an individual sperm cell is only around three months. So even if a drug does lead to a significant depletion of sperm, if the underlying spermatogonial stem cells are undamaged then those stocks of sperm will gradually be replenished.

Dr Anazodo points out that rates of infertility in the general population are around 10%-15% and can have a variety of causes, which emphasises the need to have baseline measurements of sperm function in any study or patient to be able to assess whether a drug has affected fertility.

She and her colleagues are undertaking their own prospective research to assess the potential fertility effects of cancer treatments. Newly-diagnosed cancer patients participating in the study will undergo a range of baseline fertility assessments – hormone and sperm assessments, as well as ovarian ultrasounds – then followed up over time as they undergo cancer therapy. A second component will be a longer-term analysis of fertility in patients who have completed their treatment.

Something to talk about

While there may be growing awareness of the potential effects of medical treatments on male fertility, “I’m impressed by how infrequently this is addressed in younger men,” Dr Anawalt said.

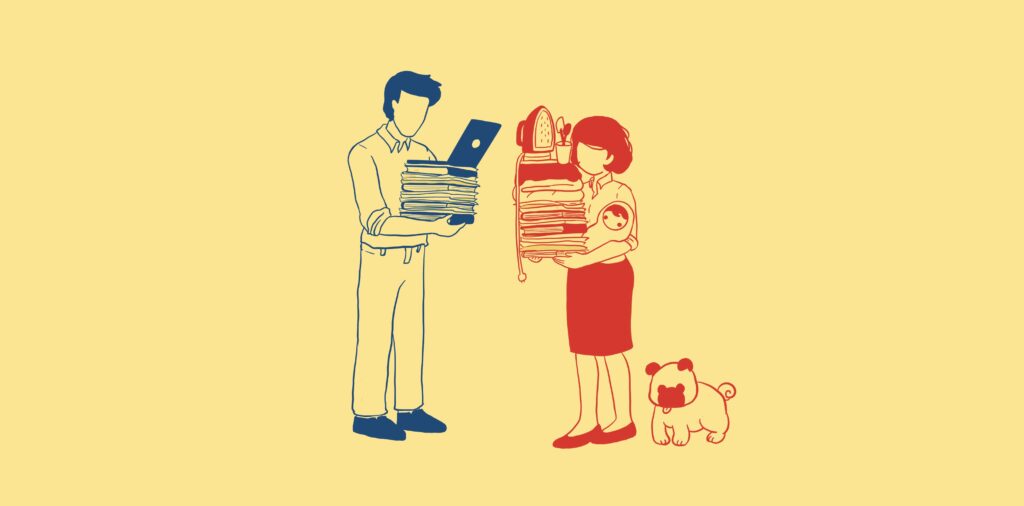

As a clinician who treats men with infertility, he sees a big difference in the way clinicians approach the issue of fertility in young men compared to young women. “This is actually one of those times where there’s a favourable bias in that women get better care than men.”

He said it is taught from medical school that when giving medication to a female of reproductive age, clinicians must consider potential reproductive side effects. Women are also more likely to ask specifically about them. “But at least United States, we prescribe medications all the time to men, and never, ever bring up the possibility it might affect their fertility,” he said.

Dr Anazodo said a more respectful approach would be to acknowledge what is known and what is unknown about potential fertility effects of a treatment.

“It’s very paternalistic to make decisions for patients without them being involved,” she said. “There’s no point telling people after they’ve had a treatment that they’re infertile, or they may be infertile.”

In Australia, cancer patients or those undergoing gonadotoxic therapies may have access to fertility preservation options, such as sperm cryopreservation. However, these facilities aren’t widespread, and may be harder to access for individuals living in rural or remote areas.

There’s also the question of what responsibility drug regulatory authorities have in ensuring that this potential adverse event is picked up as early as possible. Currently, authorities such as the TGA and FDA don’t routinely require fertility assessments to be done as part of the clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance of new treatments. But Dr Anawalt would like to see them pay attention to this aspect, particularly for drugs that are more likely to be used by men of reproductive age, which have a biological mechanism of concern, and which are of high use.

And while a rigorous assessment of male reproductive has its challenges, Dr Anawalt said it doesn’t have to be much more complex than a measure of sperm count and motility.

“It’s easy to get the data, what are the disorders that are common to young men in that age group, and, as drugs are being developed, look at this,” he said. “That’s, I think, where the greatest rewards should be.”

Illustrations by Dr Elaine Ng, a rheumatology advanced trainee based in NSW

[i] https://rheuma.com.au/gilead-pulls-plug-on-filgotinib-for-australian-ra-patients/18812

[ii] https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03201445

[iii] https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2021/03/04/2186756/0/en/GALAPAGOS-REPORTS-PRIMARY-ENDPOINT-FOR-THE-ONGOING-FILGOTINIB-MANTA-AND-MANTA-RAy-SAFETY-STUDIES.html

[iv] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanrhe/article/PIIS2665-9913(21)00041-2/fulltext

[v] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279031/