Should doctors be backing e-cigarettes?

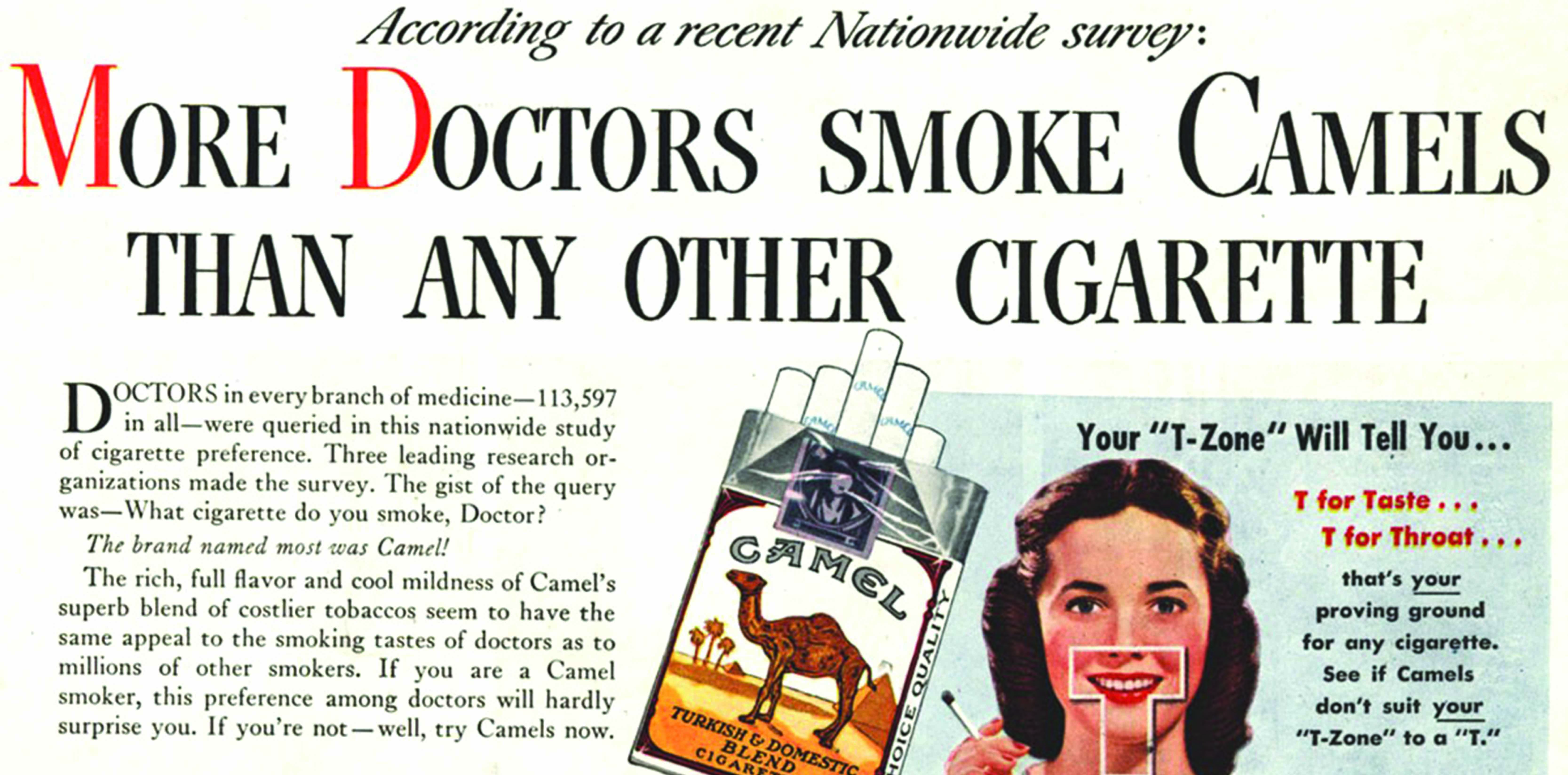

“More doctors smoke Camels than any other cigarette”, the now infamous slogan ran. “20,679 physicians say Luckies are less irritating”, claimed the competition.

While doctors’ trustworthy faces were being used to sell tobacco, it was up to the medical journals to fire the first shots in the war on smoking. Now the fight is on a new front – e-cigarettes – but this time it’s harder to tell friend from foe.

Professor Jeffrey Drazen, editor-in-chief of the New England Journal of Medicine, delivered the Ann Woolcock Lecture late last month at the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, which focuses on sleep and respiratory health. A specialist in pulmonology, he is also the Distinguished Parker B. Francis Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, professor of physiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, and a senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Professor Drazen gave an entertaining history of the rise and fall of Western tobacco use, starting with Columbus in Cuba. According to legend, the explorer’s interpreter Luis de Torres brought seeds back to Spain, grew Europe’s first tobacco plants and was locked up by the Inquisition for smoking, because “only the devil would breathe fire” – but within 18 months everyone was doing it and he was released.

Frenchman Jean Nicot brought the habit to the rest of Europe, and gave his name to the active ingredient. Tobacco plantations in Virginia brought a lucrative industry and an incentive for Europeans to move to the New World.

The invention of cigarette-rolling machines in 1880 dropped the price of a packet of cigarettes from $10 to 5c; now smoking was for everyone. But it was the world wars that brought the greatest spikes in consumption, and not only in the trenches – nurses would give wounded patients cigarettes to raise their blood pressure. Smoking was so ubiquitous and accepted that Professor Drazen’s own respected journal, the NEJM, ran cigarette ads.

A 1912 attempt to study lung tumours, then exceedingly rare, barely mentioned tobacco. In 1928 epidemiologists, looking at population data, reported that only five cases of lung carcinoma had been identified and all had occurred in excessive smokers. But the number of cases was quietly climbing.

The NEJM’s competitor, the Journal of the American Medical Association, ran Wynder and Graham’s 1950 paper, “Tobacco Smoking as a Possible Etiologic Factor in Bronchiogenic Carcinoma”, which suggested a causal link and showed the average 30-40-year lag time between starting smoking and disease symptoms.

But it was the British Medical Journal the same year that published the first of three papers by Richard Doll and Bradford Hill that put the causality beyond doubt. The research made front-page news around the world and prompted the notorious fightback by the tobacco industry.

Professor Drazen said the rise of e-cigarettes in the past decade represented “our next frontier … No war is ever over.”

He said the research community was divided down the middle, “like at a wedding”, over whether the benefits of an alternative to combustible tobacco outweighed the harms.

He cited British research showing e-cigarettes were twice as effective as conventional nicotine-replacement therapies for quitting cigarettes (18% vs 9%). But he said there was evidence that nicotine use increased the likelihood of addiction to other drugs, which was a problem given the growing concern about opioid over-use.

He also expressed concern at the array of lolly-flavoured liquids that seemed clearly targeted at children and adolescents.

Professor Drazen said he personally believed nicotine liquid should be made available over the counter, but only to adults and only unflavoured. He said he and colleagues had been petitioning the US Food and Drug Administration commissioner Scott Gottlieb, who on March 4 announced a crackdown on retailers illegally selling electronic nicotine products to minors, amid what he has called an “epidemic” of e-cigarette use among teenagers. (The next day he resigned his post at the FDA, citing family reasons, though The New York Times reported he had been under pressure from conservatives about his tough stance on e-cigarettes.)

“What’s going to happen, in my opinion,” Professor Drazen said, “is that these kids will be addicted to nicotine, and it’ll become more convenient for them, at some point in their life, to switch to combustible tobacco. So even though our smoking rates have fallen, they’re going to go up again.”