Improving education and reducing poverty could bring a surprise bonus.

Ill-founded and damaging beliefs appear to have swelled from a background hum to a full-throated shriek since the pandemic began.

Most members of the evidence-based community know by now that facts have an uphill battle against belief in conspiracy theories and distrust of vaccines, which tend to be passionately and rigidly held.

As the authors of a new paper in PNAS say, some beliefs can be unequivocally harmful: “pathological beliefs can sustain psychiatric disorders, the belief that rhinoceros horn is an aphrodisiac may drive a species extinct, beliefs about gender or race may fuel discrimination, and belief in conspiracy theories can undermine democracy”.

While dislodging specific harmful beliefs requires sustained exposure to counter-evidence, they write, improving social conditions may be an effective overall way to stop harmful beliefs rigidifying in the first place.

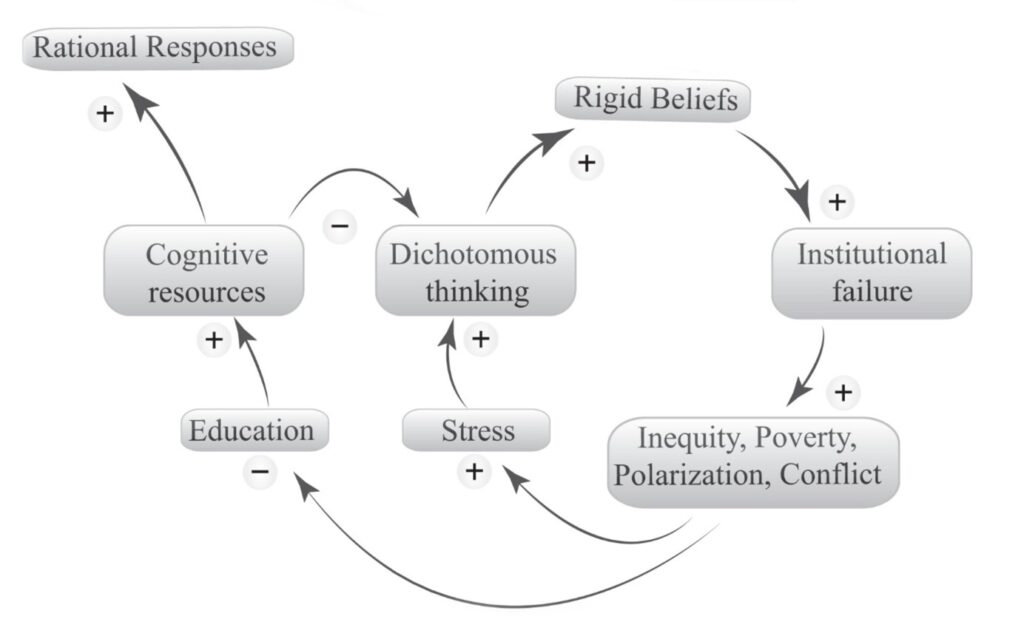

Hang on, you say, addressing things like “poverty, social cleavage and lack of education” would have many more immediate positive effects than just cutting the amount of nonsense people believe in. But the authors make a good case for interrupting the vicious cycle of stress created by harmful beliefs entrenched by stress.

The authors propose that one of the most important factors in “belief inertia” is dichotomous or black-and-white thinking. Previous studies suggest that this happens more “when there is a lack of cognitive resources, a condition which is associated with stress as well as poor educational background”. (Education may not only provide the machinery for critical thinking but may also “inoculate” young minds with balanced views and correct information.)

They also cite the neurobiological finding that “inhibition-driven competition between populations of neurons representing alternative interpretations is amplified during states of increased arousal or stress. Stress-boosted dichotomous thinking may thus well be a fundamental driver of belief rigidity … [T]he dominant role of stress also fits the observation that conspiracy theories tend to originate in times of uncertainty and crisis”.

(In contrast with dichotomous thinking, they write, tolerance to ambiguity “correlates with intellectual humility, the capacity to recognize one’s fallibility and to update beliefs in the face of new evidence”.)

“Dichotomous thinking will be more prevalent in societies where people are stressed and poorly educated. A resulting rise in pathological beliefs, conspiracy thinking, and social prejudices may, in turn, hamper societal thriving, thus implying the potential for a self-reinforcing feedback toward societal failure.”

Therefore, they argue, even a blunt approach such as universal basic income might go a long way towards making people’s belief machinery less rigid, while also reducing feelings of distrust that send them “down the rabbit hole” towards conspiracy theories and prejudiced thinking.

If you see something that shakes your faith, share it with penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.