An app that secretly photographs you to tell if you’re depressed? Delete.

Along with the classic “First do no harm”, medicine and especially medtech and especially especially medical AI could do with a “Just because you can doesn’t mean you should” rule.

AI is as we speak being auditioned for who knows how many thousands of applications in medicine, and let’s face it, not all of these hacks will be winners. An idea can be clever, brilliant even, and still not great.

The latest such enterprise to drift across the Back Page radar is this preprint out of Dartmouth College in the US, which describes an AI, called MoodCapture, taught to detect signs of depression using candid images stealthily snapped by a user’s smartphone.

Previous research along similar lines, the authors say, has used photos taken consciously in regulated conditions. The novelty here is taking images unaware and “in the wild”.

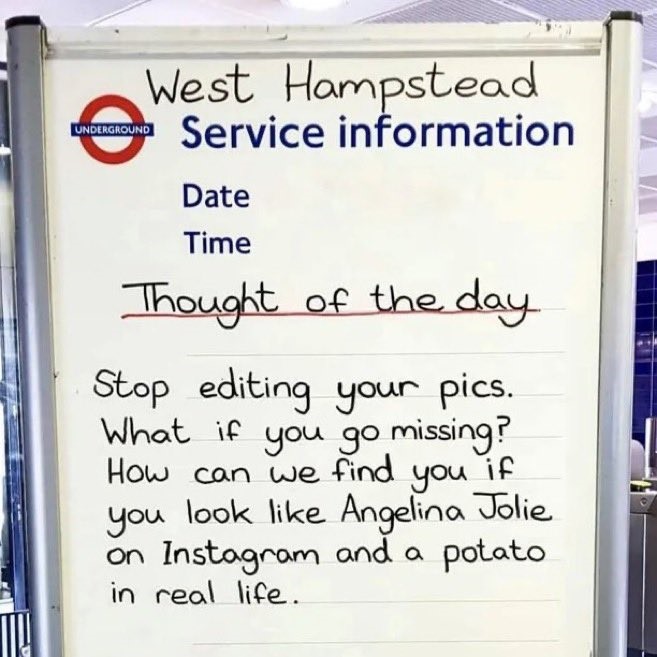

It’s certainly true that selfies may bear little resemblance to what we actually look like.

“Today,” the paper opens, “most people automatically unlock their phones using camera biometrics and face recognition. The front-facing camera quietly captures glimpses of users’ faces tens to hundreds of times daily, week in and week out. Unlike selfies, these in-the-moment images capture authentic, unguarded facial expressions, free from biases such as social desirability and self-presentation.”

Already a bit creepy.

“As smartphones have become an integral part of modern life, they are an ideal tool for unobtrusive and widespread data collection.”

True, and in itself depressing.

They trained their AI on 125,000 images collected at random times over three months from 177 people, overwhelmingly white and female, already diagnosed with major depressive disorder.

They had to install an app and complete a questionnaire three times a day about their mood. When they responded to the questionnaire item “I have felt down, depressed, or hopeless” their phone’s camera snapped a burst of photos on the sly.

The team then used machine learning and deep learning methods to train and test their MoodCapture model, using validated depression facial features such as gaze, pose and rigidity and other image characteristics like image angle, dominant colours and lighting.

The result was a model that could predict depressed/non-depressed subjects with a “promising” accuracy – 75% according to the accompanying press release, though this figure does not appear in the actual paper. The highest accuracy score the Back Page could find in the preprint itself was 60%, but the fault is probably in our reading or interpretation.

Even assuming excellent accuracy, we still have questions. Like:

Who wants this?

Your Back Page scribe is at the age when “resting b*tch face” becomes a serious danger any time we aren’t actively propping the visage up into a semblance of vitality.

Eventually the idea is for the app to learn its user, meaning it will know where the baseline is and won’t interpret every single flat-looking image as an impending mental health emergency. But that could be quite a road.

The researchers intend ultimately for no images to leave the user’s device, for privacy’s sake. Instead the images will be transformed into code for the AI to read.

While it’s reassuring that there won’t be servers full of your face not looking its best, the essential creepiness persists.

Don’t take our word for that. Here some of the subjects’ comments when asked how they felt about the prospect – and these are people who signed up for this study.

- “I don’t like being watched. I’m already paranoid when it comes to cameras.”

- “I am very uncomfortable with my appearance when I’m depressed.”

- “If I was comfortable and at home, during some of [the pictures] I may not have been completely covered.”

- “The idea of my picture being out there [makes me uncomfortable] although I know it was to be analyzed with AI.”

- “Having pictures taken and not knowing what they looked like or if they were embarrassing is an uncomfortable thing to think about.”

What will the app, or you, do with this information?

The Back Page is no expert, but it seems to us that the real challenge of depression is much less about diagnosis than it is about treatment.

Even if you do get to see a psychiatrist or psychologist, given the capacity shortage and the expense – at least in this country – finding a successful treatment regime without prohibitive side effects can be a long and arduous quest.

As for how the app responds in real time, the idea is not for it to say, Microsoft paperclip-style: “You seem to be entering a downward spiral, would you like some help?” but rather to suggest some healthy in-the-moment interventions.

“An AI application like MoodCapture would ideally suggest preventive measures such as going outside or checking in with a friend instead of explicitly informing a person they may be entering a state of depression,” says co-author Nicholas Jacobson, a Dartmough assistant professor in biomedical data science and psychiatry, in accompanying commentary.

“Telling someone something bad is going on with them has the potential to make things worse.”

Don’t you think users might get wise to those euphemisms pretty fast? And is an app that tells you to get some fresh air really going to go a long way to reducing the burden of depression?

“These applications should be paired with interventions that actively try to disrupt depression before it expands and evolves,” Professor Jacobson continues.

Ah. We’ll watch this space for those interventions.

Send story tips and no candid photography whatsoever to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.