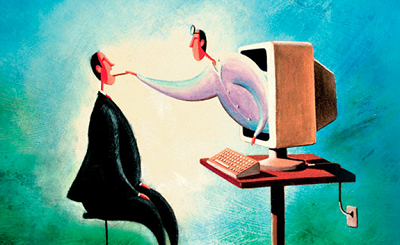

It's not the technology, says ADHA chief Tim Kelsey. It's to do with culture, financial incentives and broader policies

Digital health leaders are arguing for financial incentives and other support to speed doctors’ uptake of digital health technology.

Australian Digital Health Agency CEO Tim Kelsey said his agency was looking for solutions to the country’s slow progress on telehealth and bringing specialists into the computer age.

“Telehealth is a crucial tool. I’ve been surprised by the low uptake of services in Australia; where I’ve seen them in action they worked well,” he said.

“This is really nothing to do with technologies. It’s to do with culture, financial incentives and broader policies,” Mr Kelsey told the Australian Telehealth Conference in Sydney on Wednesday.

The ADHA chief said telehealth was used in only about 10% of appointments where it could potentially be used.

He said he had seen many communities that would clearly benefit from rapid deployment of telehealth facilities.

In Hermannsburg, in the Northern Territory, Aboriginal patients had to travel three hours on a bus to Alice Springs for specialists’ appointments and miss a day’s work, because specialists in the city did not support telehealth.

“The frustration of the clinic manager at Hermannsburg was palpable,” Mr Kelsey said.

But there was some good news on secure messaging.

“Australia is relatively unique in not having a national, reliable, high-quality address book for clinicians, which can be used for digital secure communications,” he said.

System vendors have been cooperating to set up a “federation” of their secure-message addresses to serve clinicians across Australia by a deadline at the end of 2019.

“We are optimistic that will be achieved substantially before that date,” Mr Kelsey said.

By the end of this year, the My Health Record will have achieved the two key criteria of useful clinical content and comprehensiveness, with progress in adding pathology and radiology results and linkage to public hospitals, he said.

Lacking those two critical features, the MHR had not been of value in clinical practice to date, he conceded.

Mr Kelsey said he believed the government had a role in incentivising the digital uptake, including a potential linkage of the MHR and telehealth.

“We have, and I don’t think I am speaking out of turn here, suggested that, for example, the federal government could look at some of its financial levers – including Medicare and the MBS as a whole,” he said.

The objective was to find ways, without being disruptive or confrontational, that clinicians could be encouraged to adopt digital record-keeping and other digital tools in ways that would benefit the practices, he said.

“I think there is a collective issue around supporting certain parts of the clinical workforce with the benefits case for digital record keeping and digital adoption more broadly,” he said.

“In that package, telehealth is part of the broader cultural sell that we need to collectively make,” he told delegates.

With the MHR opt-out date for all Australians looming at the end of this year, Mr Kelsey said public awareness campaigns about patients’ rights and advantages would soon begin.

“One of my concerns about expansion of the MHR is that they will expect clinicians to automatically upload content … in order to have that repository and keep their information in one place.

“We don’t know how many, but somewhere between one-third to one half of specialist community in this country don’t have computers in their consulting rooms.”