Is it OK for pharmacies to be both dispensers and retailers, or is that a fundamental conflict of interest?

Community pharmacy in Australia is changing.

As a response to income pressures and consumer behaviour, pharmacies are positioning themselves as one-stop health and wellbeing destinations, providing an expanded range of services, including immunisation and tests such as blood pressure and blood glucose measurement.

This comes on top of their more traditional roles of dispensing prescription medicines, advising on minor complaints and selling over-the-counter products.

Along with the growing role of community pharmacists comes mounting concerns about pharmacies treating their customers as both patients and retail customers at the same time and within a single environment.

In March 2017, the final report of the Review of Pharmacy Remuneration and Regulation (“the Review”) will be plonked on the federal health minister’s desk. The culmination of a consultation process over more than a year involving pharmacies, the RACGP, consumers and industry organisations, the document will report on a range of issues affecting community pharmacies in Australia, including remuneration, location rules, opening hours and health services provided. Submissions to the Review closed earlier this month.

Among its 140 questions, respondents to the Review were asked to consider the range of services and products that community pharmacies provide for their customers, the dual role of pharmacies as both health care providers and retailers, and the way this duality shapes their business, both financially and physically.

The parts of the Review’s Discussion Paper most pertinent to GPs are perhaps those relating to the medical services that community pharmacies increasingly provide, such as vaccination, wound-care management and health checks.

With pharmacies expanding their scope to provide services more traditionally associated with medical practice, the question of conflict of interest raises its head. Does the provision of healthcare in an essentially retail environment have ethical implications? Is upselling and cross-selling health-related products – some unnecessary or lacking evidence of effectiveness – appropriate in a health care setting? Where is the line drawn between pharmacist and salesperson? Should there be a line at all?

THE RETAIL AND HEALTHCARE ENVIRONMENT

Regarding the role of pharmacies as predominantly retail businesses, the review asks respondents to consider limitations on which products community pharmacies are allowed to sell. In light of the potential conflict between community pharmacies’ entwined retail and healthcare environments, the plausibility of new business models for pharmacies is also raised, whereby their retail function might be separated from their healthcare function. The RACGP’s submission was in favour of this outcome.

Submissions to the Review present a diverse range of positions, from pharmacists and their professional organisations to consumers, GPs and suppliers of products and services to pharmacies. Understandably, these groups’ perspectives differ somewhat.

PHARMACISTS’ PERSPECTIVE

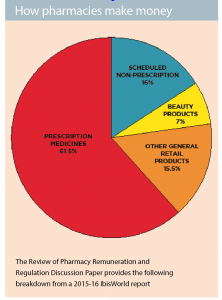

Running a profitable business in a highly regulated industry can be tricky. While Australian community pharmacies draw, on average, about 61.5% of their revenue from dispensing prescription medicines, rules about pricing structure, supply, and pharmacy locations can make business development difficult. Diversifying into retail products and services allows community pharmacies to grow their business and they say, fill their customers’ needs.

The Pharmacy Guild of Australia (“The Guild”) represents between 75% and 80% of pharmacy owners in Australia, and is the peak body with which the Commonwealth Government makes the Community Pharmacy Agreement (CPA) every five years. The CPA defines the rules on dispensing PBS medicines, providing pharmacy programs and services, and on arrangements with pharmaceutical wholesalers. As such, the Guild is one of the largest and most powerful voices for community pharmacies in Australia.

When asked to comment on the sale of complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) and other retail products in community pharmacies, The Guild provided a position statement that read, in part:

“The Guild acknowledges the widespread use of complementary medicines by the Australian population. A range of complementary medicines are available through most community pharmacies in Australia, where pharmacists and pharmacy staff play an important role in providing advice to consumers about these products.”

Furthermore, an information sheet on the Guild’s website states:

“Considering the widespread availability of CAM products, often from outlets without any health professional advice available, utilising the expertise and accessibility of community pharmacists provides a vital link between complementary and conventional medicine.”

The Pharmacy Board of Australia is to pharmacists what The Medical Board is to doctors, and develops guidelines for operating pharmacies in Australia. The Board also encourages pharmacists to provide professional advice when supplying complementary and alternative medicine. In its Guidelines on Practice-Specific Issues, it says:

“When complementary and alternative medicine is provided at a pharmacy, pharmacists should provide products of proven safety and quality. Relevant accompanying advice should be offered to assist patients in making a well informed choice regarding treatment with a complementary or alternative medicine, which should include available information on the potential benefits and harms, and whether there is sufficient evidence to support its proposed use.”

Numerous submissions to the Review from pharmacy owners echo this view. For example, a partner in a Brisbane pharmacy declared:

“Having [complementary medicines] under the watch of a pharmacist is a great way to ensure patients have access to, and information regarding these products. Even homeopathy, which I despise, is good in a pharmacy. If a patient asks me about it, I will tell them it’s useless and does nothing but placebo.”

Not everyone from a pharmacy perspective agrees that the sale of complementary and alternative products sits ethically alongside prescription medicines and health services. However, the majority appear to believe there’s a place for such therapies in community pharmacies, where they can be supplied with appropriate and relevant advice about safety, effectiveness and use.

CONSUMERS’ PERSPECTIVE

A common argument for supplying complementary and alternative therapies in community pharmacies is that consumers want them there. According to the National Prescribing Service’s Information Use and Needs of Complementary Medicines Users survey, about two thirds of Australians use complementary and alternative therapies. Some of those users purchase them from community pharmacies, and in general, consumers identify pharmacies as convenient destinations for prescription medicines, over-the-counter medicines, health advice and other products.

Between 2012 and 2014, a Consumer Needs Project was undertaken by Pricewaterhouse Coopers in cooperation with the Australian government and the Pharmacy Guild of Australia. The project included a Community Survey of 3000 participants about their experiences and expectations of community pharmacies.

The survey showed that community pharmacies were primarily used as suppliers of prescription medications, with 88% of participants reporting they used community pharmacies for that purpose.

Complementary and alternative medicines were much less frequently sought from pharmacies. Only 37% of survey participants said they used their community pharmacy as a source of these products. More popular uses of community pharmacies were to buy pharmacy-only over-the-counter medications (61% of survey participants), other over-the-counter medications (55%), other retail products (41%) and to seek advice on health-related issues (38%).

Pharmacies and pharmacists are held in high regard by the communities they serve. The 2016 Roy Morgan Image of Professions Survey rated pharmacists second only to nurses as the most ethical and honest profession in Australia.

While it’s clear from the research that community pharmacies are considered ethical and honest, many consumer submissions to the Review of Pharmacy Remuneration and Regulation expressed concern about the sale of complementary and alternative medicines.

Submission 8 from a consumer in Queensland who thought CAM had no place in pharmacies:

“Pharmacies should not be allowed to sell homeopathic or other “snake oil” treatments. What’s an uneducated consumer supposed to think when they walk into a pharmacy, a place that is trusted enough to sell opiates and cancer medication, and sees homeopathic medications sitting on the shelf? People should be able to trust that the products they buy in a pharmacy work and that is currently not the case.”

Submission 34 was from a Northern Territory consumer unhappy with the advice he was given about a supplement:

“Recently I visited a local pharmacy to fill a prescription. For the first time ever in a pharmacy I was asked if I had suffered cramps or muscle pain during the night; I truthfully replied that I had… and without any further investigation was recommended a supplement to relieve the condition.

The recommendation of a supplement, that in my opinion has limited evidence supporting its general use, in a professional medical environment caused me concern… even though I held a well-researched belief I felt under considerable pressure to purchase the item.”

Another concerned consumer suggested that simply by stocking CAM, pharmacies tacitly endorse it:

“Selling non evidence-based products alongside scientifically effective medicines confuses consumers and lends the products undue legitimacy. As evidence-based professionals, pharmacists should refuse to do it.”

BIOETHICIST’S PERSPECTIVE

Dr Wendy Lipworth is a bioethicist and health social scientist at Sydney University’s Centre for Values, Ethics & Law in Medicine. She and her colleagues see the line that separates the dispensing and retail sides of community pharmacies as quite fuzzy.

“Given the complex role that pharmacies and pharmacists assume, it is conceivable that they could sell some CAMs. But it is unquestionably inappropriate for them to sell CAMs that are known to be ineffective (e.g. homeopathic products) or harmful. If pharmacists see themselves as health professionals, then the argument that they are simply respecting their customers’ desire for these products does not hold, because the relationship between a health professional and a patient is based on a duty of care, and is therefore fundamentally different to that between a vendor and a consumer,” she said.

Dr Lipworth stressed that the combined role of “health-care-practitioner-slash-salesperson” was not limited to pharmacists, pointing out:

“Doctors who practice so-called integrative medicine already sell vitamins, and cosmetic dermatologists ‘‘sell’’ skin care products. The problem with these activities is that, even if the products ‘work’, their sale by the people who prescribe them has the potential to create real or perceived conflicts of interest. This, in turn, poses a threat to both trust in the medical profession, and the trustworthiness of medical practitioners, irrespective of how good their intentions might be.”

DOCTORS’ PERSPECTIVE

Many GPs and other medical practitioners agree in principle with Dr Lipworth’s view. In its submission to the Review, the Australian Medical Association wrote:

“The AMA agrees that pharmacists’ expertise and training are underutilised in a commercial pharmacy environment where they are distracted by retail imperatives including the sale of complementary medicines that have no basis in evidence. It would be difficult for anyone to argue that there is no inherent conflict of interest in this situation. The AMA is therefore open to alternate models of funding that would encourage and reward a focus on professional, evidence-based interactions with patients.”

Consultant psychiatrist Dr John Buchanan suggests a more prominent physical separation of dispensed medications and CAM products:

“I believe it is extremely misleading to the public for complementary medicines to be sold in the same retail environment as prescribed medication is dispensed. It puts these preparations on an equal footing when there is little evidence for the effectiveness of the vast majority of complementary medications.

My preference would be for these two kinds of preparations to be sold in completely different sections of a retail pharmacy.”

THE ETERNAL QUESTION

Not surprisingly, the views of consumers, GPs, academics and pharmacists on community pharmacies are far from consistent.

Whether they are characterised as shops that provide health services, or health practitioners who sell products largely depends on who you are. And though community pharmacies are highly regarded, the non-medical products they sell, and the manner in which they are sold, remain strong areas of contention.

Until we have agreement on the desired role and business model for community pharmacy, the ethical question of whether complementary and alternative therapies belong on their shelves remains.

Perhaps the report of the Review of Pharmacy Remuneration and Regulation will bring us closer to an answer.

Up for discussion: Prescription drugs and retail products – are they compatible?

• Should there be limitations on some of the retail products that community pharmacies are allowed to sell? For instance, is it confusing for patients if non-evidence based therapies are sold alongside prescription medicines?

• Would a community pharmacy that focused solely on dispensing provide an appropriate or better health environment for consumers than current community pharmacies? Would such a pharmacy be attractive to the public? Would such a pharmacy be viable?

• More generally, is there a need for new business models in pharmacy? If so, what would such a model look like and how would it lead to better health outcomes?

• Does the availability and promotion of vitamins and complementary medicines in community pharmacies influence consumer buying habits?

• Should complementary products be available at a community pharmacy, or does this create a conflict of interest for pharmacists and undermine health care?

• Do consumers appreciate the convenience of having the availability of vitamins and complementary medicines in one location? Do consumers benefit from the advice (if any) provided by pharmacists when selling complementary medicines?

• Does the “retail environment” within which community pharmacy operates detract from health care objectives?