What are the implications of primary aldosteronism for the general practitioner? Dr Pieter Martijn Jansen outlines this common condition

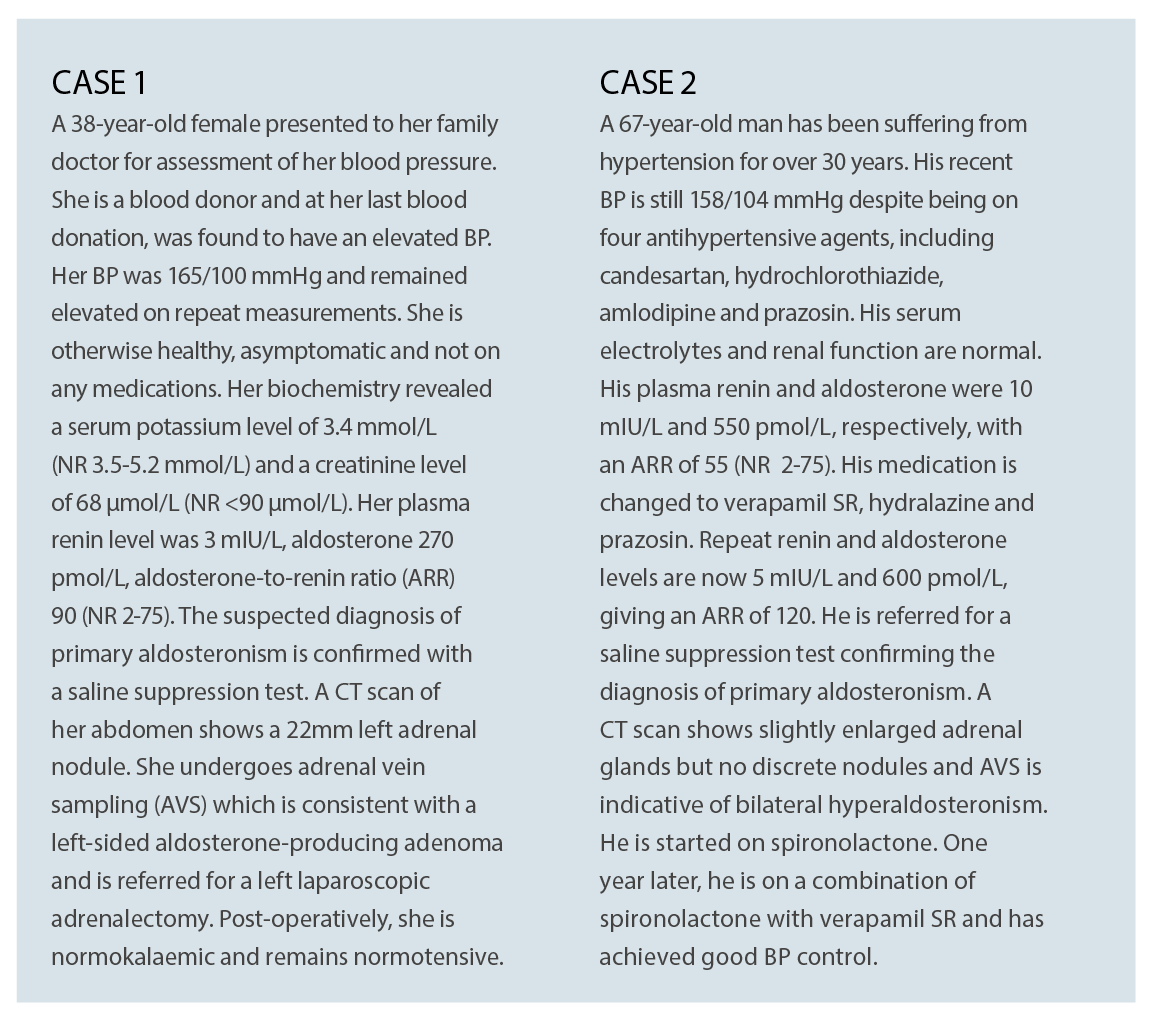

The following two case studies, presented below, are fictional, but serve as examples of two common presentations of primary aldosteronism. This condition is now well-recognised as the most common form of secondary hypertension with a high prevalence amongst patients seen in specialised hypertension clinics.1

As hypertension is a very common entity in the general population, primary aldosteronism is also expected to be prevalent in primary care patients. Despite this, it remains a condition that is underdiagnosed.2

In a recent article in the Medical Journal of Australia, Yang et al make a case for earlier and wider screening of hypertensive patients for primary aldosteronism that will shift this more into the domain of primary care.3

This article aims to discuss the context and implications for the general practitioner.

WHAT IS IT?

Primary aldosteronism is a condition characterised by autonomous production of aldosterone by one or both adrenal glands. This results in hypertension as a result of increased renal sodium reabsorption, and frequently leads to hypokalaemia due to excessive renal potassium excretion.

The classic case of this condition was described by Jerome Conn in the 1950s. He described a young woman with hypertension and hypokalaemia who was found to have an aldosterone-producing adenoma, which has become known as “Conn’s disease”.4

Since then, primary aldosteronism has been recognised as a well-known cause of secondary hypertension, but for many years was also considered a very rare condition. This was largely due to the fact that hypokalaemia was thought to be a necessary hallmark of its presentation.

This changed with the introduction of the aldosterone-to-renin ratio (ARR) in the early 1980s.5 The aldosterone-induced increase in tubular sodium reabsorption and the subsequent rise in extracellular volume results in a compensatory decrease in plasma renin, which is the other hallmark of primary aldosteronism.

The ARR is thought to be able to detect more subtle imbalances in aldosterone and renin and since its introduction as a screening test, primary aldosteronism was found to be much more common than previously thought.

A recent meta-analysis reported a prevalence amongst patients in referral centres from 4.2% with stage 1 to 16.4% with stage 3 hypertension, although a high observed study heterogeneity precluded any firm estimates of the real prevalence.6

The increase in case detection has also resulted in advances in understanding of the disease. It is now known that the most common subtype is bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, accounting for roughly two thirds of cases and the classic aldosterone-producing adenoma for approximately one third.7

Other subtypes are adrenocortical carcinoma, bilateral macronodular disease and glucocorticoid-remediable aldosteronism but these are considered to be rare. It has also become apparent that only a minority display the classic feature of hypokalaemia7 and this explains why many cases have remained and continue to remain undetected.

Furthermore, there is now ample evidence that aldosterone is an important mediator of target-organ damage such as myocardial and perivascular fibrosis.8

Clinical studies have confirmed that patients with primary aldosteronism have higher cardiovascular complication rates than can be explained by hypertension alone9 illustrating the damaging effects of long-term aldosterone excess.

HOW TO DIAGNOSE

Establishing the diagnosis is a multi-step process.10

The ARR is now widely accepted as the screening test of choice, but as any screening test, it can have false-positive results, so it is important to follow up the diagnosis with a confirmatory test.

Several confirmatory tests are in use, but the two most widely used are the saline suppression test and the fludrocortisone suppression test.

A detailed outline of the different test procedures goes beyond the scope of this article, but the principle is generally the same, that is, to assess whether the adrenal glands are capable of suppressing aldosterone production in response to salt loading. The inability to sufficiently suppress aldosterone indicates autonomous aldosterone overproduction.

The final step is to assess for lateralisation, or in practical terms, to determine whether there is an aldosterone-producing adenoma or bilateral adrenal hyperplasia. This step usually includes imaging of the adrenal glands, typically a CT scan of the adrenals, but the gold standard is adrenal vein sampling. (AVS)

AVS is an invasive procedure performed by an interventional radiologist to obtain blood samples from both adrenal veins for measurement of aldosterone to assess whether the aldosterone overproduction is uni- or bilateral.

This final step is crucial to determine the best management. In unilateral disease, the preferred management would be surgical (that is, unilateral adrenalectomy) which could potentially cure or at least substantially ameliorate the hypertension. In bilateral disease, the management would be pharmacological.10

Treatment with aldosterone receptor antagonists, such as spironolactone, in most cases also results in a great improvement in blood pressure, a reduction in the use of other antihypertensives and control of hypokalaemia, if present.

The excess cardiovascular morbidity associated with hyperaldosteronism in combination with the availability of targeted treatment options including a potential cure in surgical candidates highlights the importance of effective case detection and diagnosis.

SCREENING IN PRIMARY CARE

The process of case finding and diagnosis has mostly been the area of second-line specialists, such as general physicians, endocrinologists, cardiologists and nephrologists.

As argued by Yang et al,3 however, it may be time to shift our screening efforts to primary care. This would potentially have several benefits. As highlighted in the previous paragraphs, long-term exposure to excessive aldosterone is associated with increased cardiovascular complications and end-organ damage.

It would make sense to assume that screening earlier in the course could prevent some of the complications by offering patients either surgical cure or targeted pharmacotherapy. Another possible advantage is that screening is likely easier to conduct in the treatment-naive or mildly hypertensive patient.

Although the ARR is the best screening test available, it is not without limitations. Numerous factors are known to influence the ARR, including posture, time of sampling and dietary salt intake but most of all medications.10

Of the antihypertensives, diuretics (including potassium-sparing), angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-i) angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARB) and dihydropyiridine calcium channel blockers can lead to a false-negative results by increasing plasma renin and beta-adrenergic receptor blockers to false-positive results due to a decrease in renin and a subsequent increase in ARR.10

Especially in multi-medication regimes, the ARR can be difficult to interpret and it is advised to change treatment to agents with minimal interference with the ARR before repeating the test. Examples of non-interfering agents are non-dihydropyridine calcium antagonists (such as verapamil SR, hydralazine, prazosin and moxonidine).10

However, this can be problematic and sometimes impossible in patients with severe hypertension on multiple agents. Screening earlier in the process can potentially overcome these limitations as patients are more likely to be on less or no medications enabling the clinician to obtain a “pure” ARR with minimal interfering factors.

There are a few questions yet to be resolved.

First of all, it is important to consider that the predictive value of a diagnostic test depends on the prevalence of the condition in the population screened. Importantly, a lower prevalence will result in a higher rate of false-positive results. This in turn may lead to further unnecessary diagnostic testing with its associated risks and costs. It may also result in overtreatment and, not unimportantly, unnecessary concern and anxiety in some patients.

The prevalence of primary aldosteronism in the primary care setting has not been studied extensively.

The aforementioned systematic review had identified nine studies in primary care with reported prevalences among hypertensive patients between 3.2 and 12.7%.6

A recent study aiming to screen consecutive hypertensive patients in primary care practices showed a prevalence of 5.9%.11

It is important to consider which patients should be screened. In this particular study, the prevalence was 3.9% in stage 1 and 11.8% in stage 3 hypertensives.11 Another study showed a prevalence of 6.8% in patients with prehypertension12 although the total numbers were very small. And even in normotensive subjects the prevalence of biochemical primary aldosteronism was found to be at least 1.8%.13

In addition to the risk of false-negative results, the other important question that needs consideration is whether early screening will indeed lead to better outcomes, in this context enabling cure in some patients, improving blood pressure control in other and mitigation of cardiovascular risk in all.

Data on this is not available and further studies are needed to prove that patients will have a better outcome if diagnosed earlier in the disease and that early screening is also cost-effective.

It should furthermore be noted that increased screening can only be effective if a clear referral pathway is available for patients who test positive.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Primary aldosteronism is an important cause of hypertension associated with an excessive cardiovascular complication rate as compared to essential hypertension. Targeted treatment is available and the choice of treatment depends on the subtype.

The diagnostic approach for screening, confirmation and subtyping has been well described and serves to select the right treatment for the right patient.

Primary aldosteronism is currently underdiagnosed in primary care and there are convincing arguments in favour of broader first-line screening.

There are remaining questions that need further study including the diagnostic accuracy of available screening tools in the primary care setting, whether this approach will eventually result in better outcomes and whether they are cost-effective.

For now, general practitioners should be aware that primary aldosteronism is not uncommon and should be be considered in all hypertensive patients.

The Endocrine Society has developed guidelines to help decide which patients will benefit from screening for this disease.

These are patients with: 10

• A sustained BP above 150/100 mmHg on repeated measurements

• Uncontrolled hypertension (BP>140/90 mmHg) despite at least three antihypertensives, including a diuretic

• Controlled hypertension (BP<140/90 mmHg) on at least four antihypertensive agents

• Hypertension and spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalaemia

• Hypertension and an adrenal incidentaloma

• Hypertension and sleep apnoea

• Hypertension and a family history of early-onset hypertension or cerebrovascular accident (<40 years)

• Hypertension and a first-degree relative with confirmed primary aldosteronism

A stronger awareness and implementation of these guidelines in primary care will most likely help to achieve a higher case detection rate. This will, in turn, provide better insight into the prevalence of the condition in the primary care population.

Whether broader screening in patients with mild forms of hypertension will further reduce the burden of this disease is yet to be discovered, but will hopefully become clear over time.

Dr Pieter Martijn Jansen is an endocrinologist at Princess Alexandra Hospital and lecturer at University of Queensland. He has a PhD on the role of aldosterone and aldosterone blockade in hypertension

References:

1. Stowasser, M., R.D. Gordon, T.G. Gunasekera, D.C. Cowley, G. Ward, C. Archibald, and B.M. Smithers. High rate of detection of primary aldosteronism, including surgically treatable forms, after ‘non-selective’ screening of hypertensive patients. J Hypertens 2003; 21(11):2149-2157.

2. Mulatero, P., S. Monticone, J. Burrello, F. Veglio, T.A. Williams, and J. Funder. Guidelines for primary aldosteronism: uptake by primary care physicians in Europe. J Hypertens 2016; 34(11):2253-2257.

3. Yang, J., P.J. Fuller, and M. Stowasser. Is it time to screen all patients with hypertension for primary aldosteronism? Med J Aust 2018; 209(2):57-59.

4. Conn, J.W. Presidential address. I. Painting background. II. Primary aldosteronism, a new clinical syndrome. J Lab Clin Med 1955; 45(1):3-17.

5. Hiramatsu, K., T. Yamada, Y. Yukimura, I. Komiya, K. Ichikawa, M. Ishihara, et al. A screening test to identify aldosterone-producing adenoma by measuring plasma renin activity. Results in hypertensive patients. Arch Intern Med 1981; 141(12):1589-1593.

6. Kayser, S.C., T. Dekkers, H.J. Groenewoud, G.J. van der Wilt, J. Carel Bakx, M.C. van der Wel, et al. Study Heterogeneity and Estimation of Prevalence of Primary Aldosteronism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101(7):2826-2835.

7. Mulatero, P., M. Stowasser, K.C. Loh, C.E. Fardella, R.D. Gordon, L. Mosso, et al. Increased diagnosis of primary aldosteronism, including surgically correctable forms, in centers from five continents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89(3):1045-1050.

8. Young, M.J. Mechanisms of mineralocorticoid receptor-mediated cardiac fibrosis and vascular inflammation. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2008; 17(2):174-180.

9. Milliez, P., X. Girerd, P.F. Plouin, J. Blacher, M.E. Safar, and J.J. Mourad. Evidence for an increased rate of cardiovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45(8):1243-1248.

10. Funder, J.W., R.M. Carey, F. Mantero, M.H. Murad, M. Reincke, H. Shibata, et al. The Management of Primary Aldosteronism: Case Detection, Diagnosis, and Treatment: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; 101(5):1889-1916.

11. Monticone, S., J. Burrello, D. Tizzani, C. Bertello, A. Viola, F. Buffolo, et al. Prevalence and Clinical Manifestations of Primary Aldosteronism Encountered in Primary Care Practice. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 69(14):1811-1820.

12. Ito, Y., R. Takeda, S. Karashima, Y. Yamamoto, T. Yoneda, and Y. Takeda. Prevalence of primary aldosteronism among prehypertensive and stage 1 hypertensive subjects. Hypertens Res 2011; 34(1):98-102.

13. Karashima, S., M. Kometani, H. Tsujiguchi, H. Asakura, S. Nakano, M. Usukura, et al. Prevalence of primary aldosteronism without hypertension in the general population: Results in Shika study. Clin Exp Hypertens 2018; 40(2):118-125.