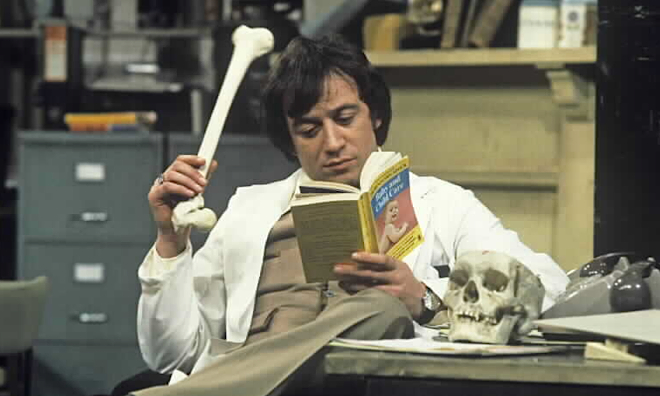

Communicating diagnostic uncertainty with patients can be fraught with danger and there has been very little guidance on how to go about it

Uncertainty is an integral part of medical practice, but there has been very little guidance on how to communicate that to patients. That is, until now.

Implying, rather than saying outright, a diagnosis was unclear appeared to be most likely to keep patients approving of, and trusting, their doctor, a survey of 71 parents of paediatric patients found.

Phrasing diagnostic uncertainty in terms of broad differential diagnosis or likelihoods, such as “it could be this disease or that disease” or “it is most likely this disease”, was better received than explicitly saying “I’m not sure which disease this is”.

In fact, implicitly conveying diagnostic uncertainty led to a greater perception of the physician’s competence, better trust and confidence, and a greater intention to adhere to instructions when compared to the explicit phrasing.

“Misdiagnosis is common in medical practice and to enable improvements, uncertainty of diagnosis is something both doctors and patients will need to embrace,” senior author Dr Hardeep Singh, researcher at the Baylor College of Medicine, said.

While it is essential to communicate diagnostic uncertainty to ensure patients are receiving true shared decision-making, research shows that it can be fraught with danger.

Numerous studies had shown patients were less satisfied, listened to their doctors’ instructions less, and had lower trust and confidence in their doctors when faced with diagnostic uncertainty, the authors said.

Until now, the best way to communicate this diagnostic uncertainty had been unknown, with doctors left to their own personal experience to guide the discussion.

“If communicated very openly, patients may appreciate the honesty or may react negatively to the doctor’s lack of knowing what health problem they have,” the authors explained. “Conversely, strategies that communicate in a more-subtle fashion could suggest to patients that while actual diagnosis may not be known yet, several possibilities are being considered.”

The researchers compared three different vignettes that first included a common clinical scenario about a child becoming sick with stomach pain and then receiving tests results that were inconclusive.

The parents were split into three groups, which were each presented with different ways of communicating the diagnostic uncertainty: explicit communication, implicit communication using differential diagnosis and implicit communication using most likely diagnosis.

All parents then received the same future plan for diagnosis, which included the doctor comforting the parent and detailing a plan to determine the cause of the pain, which included more visits and tests over the upcoming fortnight.

Given how critical managing uncertainty was in patient-centred communication, the authors suggested that improving this skill could have knock-on effects for the therapeutic relationship and long-term health outcomes.

Int J Qual Health Care; online 10 January