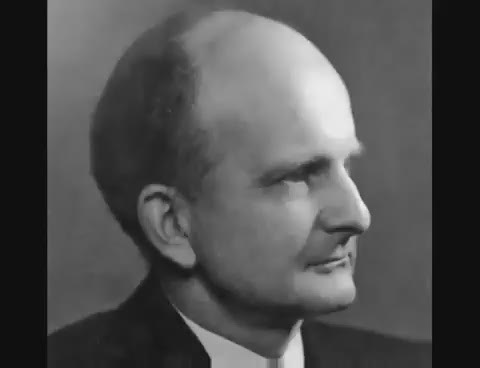

The man who first described Munchausen’s Syndrome was a fascinating individual

Today everyone has heard of Munchausen’s Syndrome, but the man who first described the condition – and gave it the enticing name – is all but forgotten.

Richard Asher was a superb physician who changed medicine and psychiatry and left some important lessons that we still need to learn. One of the foremost medical thinkers of his time, his thinking was characterised by clear logical ideas.

The son of a cleric and coming from a musical family, Asher was a gifted, insightful and creative doctor, well versed in literature with a preoccupation that medical writing was turgid, jargon-laden and boring – for example as stated in his 1958 paper, ‘Why are medical journals so dull?’.

Asher married music teacher Margaret Elliot and they had three children: Peter Asher a musician (“World Without Love”) and producer; Jane, actress and longtime girlfriend of Paul McCartney; and radio actress Clare.

Trained as a physician in haematology and endocrinology, Asher was determined to challenge the existing shibboleths in a hidebound discipline that was slow to change. Friendly with Richard Doll and Archie Cochrane, he was a champion of Evidence-Based Medicine long before it became generally accepted. Asher argued passionately in favour of generalists and warned against over-specialisation. He protested at the incarceration of old people in institutions and deplored the epidemic spread of committees. These ideas are as relevant today as they were in his time.

Describing himself as a physician more at home at the bedside than in the laboratory, he advised students to ignore textbooks and to think for themselves. He poured out articles that were marvels of concision, laden with literary allusions and rational conclusions. He showed that Pel-Ebstein fever was a condition that only existed in name. He pushed manufacturers to make clinical thermometers which would register hypothermia.

Asher was innovative and prepared to look at unconventional approaches if they could solve the problem. His outstanding work led to a number of discoveries, notably his paper on Myxoedematous Madness, something had been poorly understood.

The most important issue he pursued was to end the practice of keeping patients in bed for lengthy periods. Asher was certain this was not only counter-productive but dangerous, leading to unnecessary complications like deep vein thrombosis. In doing so, he changed medical treatment for all time and saved many lives. His 1947 article is regarded as one of the most influential medical papers ever written.

Interested in the psychological aspects of illness, Asher could have had an alternate career in psychiatry. He may have avoided this because the field was caught up with psychoanalytic ideas, which he abhorred, and tended to ignore the somatic aspects of mental disorders. Today he would have made an outstanding liaison psychiatrist. Instead he ran the mental observation ward at the Central Middlesex Hospital caring for patients with psychological symptoms.

As a highly observant physician, in 1951 Asher described a series of patients that caused intense problems in hospitals. He commenced with: “Here is described a common syndrome which most doctors have seen, but about which little has been written.”

They were young males who would present to casualty with dramatic symptoms of serious illness, have elaborate explanations that conveniently covered up their past and were determined to be admitted for treatment. Once in, their symptoms would multiply, as would their demands for treatment, both drugs and surgery. Some engineered so many operations they had ‘noughts-and-crosses’ abdomens. They would cause havoc in the wards, often setting up other patients against the staff.

When the inevitable happened and they were confronted, their response was to get angry and storm out. Background checks of these patients showed that they had extensive hospital records, would travel widely to seek admission and go to extraordinary lengths to create symptoms, such as swallowing glass or injecting faeces. In hospital, they could sabotage treatment by pulling out sutures or misusing drugs.

Asher realised that these patients had a pathological need to seek treatment and went about it in a way that was little short of psychopathic. He named the syndrome after the fictitious Baron Munchausen, famed for his telling of fantastic tales about his adventures. These patients told elaborate stories to elicit sympathy that were always extremely difficult to penetrate. This is known as pseudologia fantastica.

Never short for words, he listed three categories: laparotomophilia migrans; haematemesis merchants; and neurological type. However, over time it was evident that Munchausen’s patients could present with every type of symptom, including psychiatric problems and these categories became redundant.

What lay behind the motivations of these patients was extremely difficult to penetrate. All attempts to assess them psychiatrically were blocked and they were even more uncooperative with treatment – every attempt failed. While seeking narcotic drugs and the care of a hospital ward is understandable, why would someone want to submit themselves to painful and at times mutilating surgery that was unnecessary? And, of course, after a few procedures, they often had recurrent and genuine complications.

Munchausen’s Syndrome posed important questions about the doctor-patient relationship that we are still dealing with today. The closest explanation is that these patients have an emotionally deprived childhood where their need for care becomes linked with treatment. They often have experience of serious illness when young, either in themselves or relatives and a surprising number had parents involved in health care, such as nurses or attendants.

Illness behaviour is not a static thing and evolves over time. Modern Munchausen’s patients can include as many, if not more, women. Rather than constantly moving, they often stay locally and have a family. These relationships are invariably pathological and they tend to present recurrently to the same hospital. Some of them work in health and there are even recorded cases of Munchausen doctors.

A notorious example is trainee nurse Beverley Allitt, who would present regularly to the casualty of the hospital where she worked with injuries produced by dropping a stone on her hand. Allitt went on to murder four out of eleven children that she was nursing, earning for herself the soubriquet of The Angel of Death.

Munchausen’s Syndrome and its variants has fallen foul of the name police and is now known by the dreary title of Factitious Disorder. It includes the more controversial condition of Munchausen’s Syndrome by Proxy. This state is deeply misunderstood and has led to a number of false convictions for murder.

Asher had his faults of course, including excessive reliance on hypnosis and a tendency to dismiss some patients as malingerers. He eventually fell foul of medical politics. In 1964, it was decided that the ward should be run by a psychiatrist, not a physician and he had to go. It was a pity some compromise could not be reached to allow him to stay in some capacity. Asher could not come to terms with the situation and stopped working. Tragically, in 1969 he took his life, confirming the opinion of some that he had a manic-depressive disorder although the evidence for this is questionable.

Richard Asher left us a marvellous legacy of erudite papers, witty apercus and clinical thinking that will never date. The best introduction is the anthology ‘Talking Sense’, a title that sums up his medical ethos. Physicians come and go but there are few who truly live up to the best Hippocratic principles: Richard Asher was one of them. His tragic end is a reminder of how often our best talents are destroyed by the system that they seek to serve.

Robert M Kaplan trained in liaison psychiatry – a marvellous and often neglected field – and discussed Munchausen’s Syndrome in his book Medical Murder: Disturbing Tales of Doctors Who Kill.