An Australian pain expert outlines a set of protocols GPs can use to navigate the complex clinical and ethical issues surrounding opioid prescription

Ask some medical registrars these days what the protocol is for prescribing opioids for pain and they will tell you the protocol is irrelevant. You just don’t do it. “That’s what an older generation of doctors did and some still do. We won’t.”

Ask many GPs and they, too, will be likely to report increasing reluctance to prescribe the once-feted pain relief medications, some fearing being targeted by the PSR following a previous campaign to “warn” supposed over-prescribers.

But the situation just isn’t as simple as it is often portrayed, according to some pain experts. There are ethical issues when it comes to patient access to pain relief and many experts are saying that, given the right circumstances, patients can be prescribed opioids for pain relief and, what’s more, should be prescribed this class of drugs. It’s even in a UN charter.

While there is no doubt, the widespread adoption of opioids in medicine was a mistake, it should never have been the first-line in treatment of pain or as an ongoing treatment for chronic pain, experts are saying that circumstances do exist where at least a trial of opioids is warranted.

But the key issue these days is knowing who warrants an opioid trial, which opioid, and which form, and for how long. In addition, doctors need to have in place, from the outset a clear framework of how this patient’s opioid use will be monitored and its effectiveness assessed. Certainly a million miles away from the prescribe-and-go practice of old.

To provide context for the responsible and safe prescription of opioids, one needs to look at a number of areas, according to Professor Milton Cohen, a specialist pain medicine physician and rheumatologist with the St Vincent’s Clinical School, UNSW. These include the prevalence of opioid use, the prevalence and complexity of chronic non-cancer pain, and the current regulatory climate that has arisen as a result of the issues of opioid over-prescribing in the last decade.

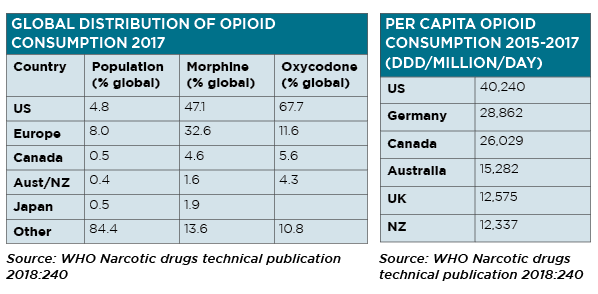

The US has just under 5% of the world’s population, but uses two-thirds of the world’s oxycodeine and nearly half its morphine. Closer to home, Australia has 0.4% of the world’s population and uses 1.6% of the world’s morphine and 4.3% of the world’s oxycodone.1 Nearly 85% of the rest of the world has virtually no access to these important therapies for chronic pain.

Prevalence of chronic non-cancer pain

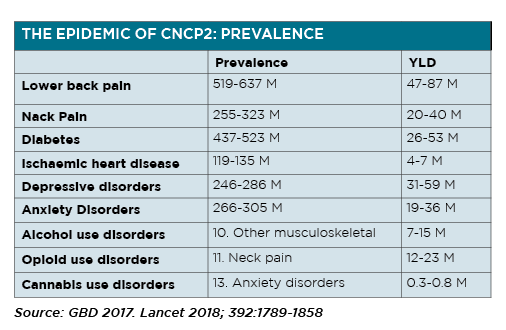

The Global Burden of Disability (GBD) study2 has found that chronic non-cancer pain prevalence is at near epidemic proportions. Looking at years lived with a disability, which is a composite estimate of the prevalence of a condition and its weight for disability, it appears that pain syndromes make up the top two most common disability disorders, specifically low back pain and headache disorder.

They have a higher prevalence than diabetes and heart disease, and are closely associated closely with depression and anxiety disorders.

Chronic non-cancer pain is a complex phenotype, says Professor Cohen.

An Australian study of more than 1500 patients who were chronic opioid users (>six weeks),3 found the typical patient had a low income or was unemployed, had multiple pain conditions and poor physical health, had depression and/or anxiety, had had suicidal ideation( around 40%), concurrently took antidepressants (>50%) and/or benzodiazepines (around 30%).

There was also often an association with abuse and/or neglect, and high rates of alcohol and cannabis use.

“Looking at the ethics involved, you might say that patients are opiophilic, and have a right to pain relief,” Professor Cohen says.

“On the other side of the ledger, there’s always been a question about a patient’s motivations in seeking pain relief about how specific or otherwise that might be.”

But considering the complexity of the population of people with chronic non-cancer pain, and the not insignificant morbidity and mortality associated with the use of opioids, Professor Cohen says opioids should not be considered a core component of the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain.

“Optimal treatment, these days emphasises moving to active self-management strategies, as opposed to relying on passive treatments. And included in passive treatments are, of course, medications,” he says.

Professor Cohen says this is the principle that underpins chronic non-cancer pain management and can help provide the framework for safe and responsible prescribing of medications and opioids in particular.

He says that in pain medicine, “we now talk about a socio-psycho-biomedical model to emphasise that the psychological and the social dimensions are just as important, if not more than important in the experience of chronic pain”.

Consequently, the key to chronic non-cancer pain management is the comprehensive assessment of the patient, not only of their pain and physical disability but also of their circumstances, their comorbidities and their expectations.

Comprehensive assessment plus goal setting

In assessing the patient with chronic pain, along with noting the nature and cause of the pain, its duration and severity, and exacerbating and relieving factors, Professor Cohen points out the importance of determining the patient’s expectation in terms of pain relief, and how realistic this might be.

He gives the example of a patient with severe osteoarthritis of his knees, who lives on the fourth floor of a building with no lift.

Such a patient “is going to have persistent knee pain no matter what you do”.

Patients and doctors need to agree on realistic goals, both in terms of symptom relief and functional capacity. Professor Cohen suggests asking the patient how they would like their life to change even though they’re living with pain, and not just in terms of physical activity but also personal activity.

Once goals are agreed upon, a plan is then devised how these goals can be achieved and this needs to include physical activity, non-drug therapies as well as drug intervention.

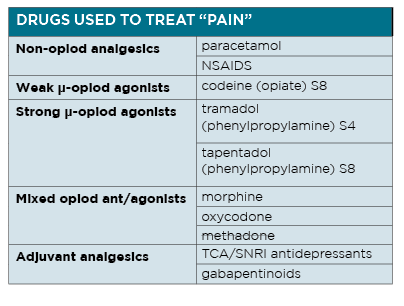

The decision as to which therapeutic agent to use to “treat” pain is complex, not least because of the sheer number of potential treatments available.

Many patients with chronic pain will have already been prescribed some, if not many, of these agents and report varying rates of effectiveness.

It is important to ensure non-opioid options have had an adequate trial, using appropriate doses over a reasonable amount of time, before being branded as ineffective.

Contract and conduct in an opioid trial

Patients with severe non-cancer pain despite an adequate trial of non-opioid treatments, including physical, pharmaceutical and psychological therapies might be considered for an opioid trial.

In a contractual approach Professor Cohen says that setting realistic goals at the outset is vital. There should be only one prescriber or team, there should be options for monitoring and “opioid responsiveness” should be assessed effectively and quickly.

The basic principles to consider when conducting an opioid trial include starting with controlled release transdermal or oral preparation and starting at a low dose and titrating up, trying to avoid breakthrough doses especially parenteral opioid doses.

And key to ensuring the trial of opioids is safe and effective, is regular review. Professor Cohen suggests adopting the 5As protocol when monitoring patients commencing an opioid treatment – that is check the patient for Analgesia, Activity, Affect, Adverse effects and Aberrant behaviours.

It is also very important to know when to declare a fail, he suggests. Patients should not have their opioid dose increased beyond a ceiling of 40-60mg/day (oral morphine equivalent) if they have had had no response. If you’re not getting a response signal under this level, your patient is not opioid responsive, he says.

In addition, there needs to be a mechanism built in to regular monitoring that allows for tailoring of the opioid dose to adequately cover exacerbations and periods of remission in the course of the patient’s condition. If the patient is opioid responsive, it is important to have the medication titrated to the lowest effective dose.

An inheritance problem

A common issue for GPs is “ inheriting patients” on long-term opioids for chronic pain, says Professor Cohen. Particularly patients originally treated in hospital following trauma,” who have been a been given a big stack of short acting opioids.”

In these instances “follow the natural history of healing”, Professor Cohen says.

The opioid dose needs to be tapered down, again with regular review and close monitoring, remembering that this too is not a set and forget situation.

He concedes this is a difficult situation for GPs, as they are starting from the point of having to start a new “contract’.

Response to difficulty in achieving goals

In the real world, success is not always a given especially in the case of an opioid trial. Some patients will not see an improvement in their symptoms, some patients won’t get adequate pain relief despite an improvement in function, some patients won’t be compliant with their medication regimen and worse still some patients will have unsanctioned use of their opioid.

Regular review and monitoring will alert the prescriber to this occurrence, and they then need to consider further action. This can include the establishment of a new contract with new goals or perhaps a tapering of the opioid until the medication is ceased.

Often there is no alternative but to return to the starting point of a comprehensive social, psychological and biomedical assessment.

Conclusion

Despite the widely publicised dangers associated with opioid use, traditional opioids may still have a role in the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain in general practice.

According to Professor Cohen, to ensure the safe and responsible use of opioids in general practice, the prescriber will:

Recognise the complex phenotype of chronic non-cancer pain

Perform a comprehensive assessment of the patient with chronic non-cancer pain

Ask, is this patient’s predicament likely to be opioid-responsive?

Monitor ongoing trial of therapy with a “contractual approach to opioid usage”

Go low and slow

Note: Comments from Professor Cohen in this article are drawn largely from a talk he gave to Healthed’s Annual Women and Children’s Health update in 2019 in Sydney.

References:

WHO Narcotics Drugs Technical Publication 2018:240

GPD 2017. Lancet 2018; 392:1789-1858

Campbell et al, Pain 2015;156:231-242; NDARC , UNSW Sydney