Look, maybe this one wasn’t the biggest health priority on the planet, but we’re overjoyed all the same.

We all know the feeling. You’ve chomped down onto the sweet, icy surface of a soft cone, exposing the sensitive part of your teeth to the cold, and you know right away that a splitting ice cream headache is on its way.

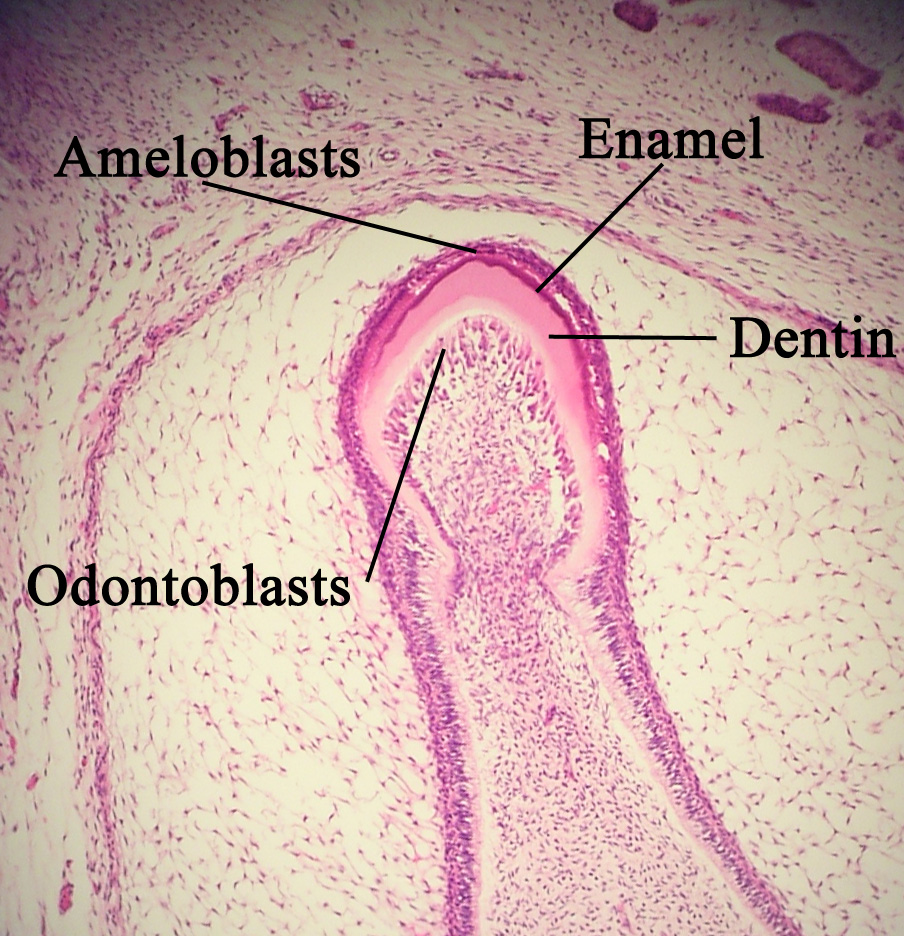

The biological cause of ice cream headaches has been a mystery in the past. But researchers have just discovered the culprit – a cold-sensitive protein called TRPC5 that is found inside tooth cells called odontoblasts, which sit just under the enamel and dentin.

The study, published in Scientific Advances, showed that mice lacking the TRPC5 protein (and mice where the TRPC5 protein had been blocked) had no nerve response when their teeth were dipped in an ice-cold solution.

Normal mice did have a nerve response to cold stimulation on their teeth, which pinpointed this protein as the main cold sensor.

The researchers then turned their attention to whether TRPC5 was also a cold sensor in human teeth and expressed in human odontoblasts.

They examined healthy human teeth from adults, removed for orthodontic or cosmetic reasons, and found TRPC5 in the odontoblastic layer.

The TRPC5 protein is an ion channel that allows signalling chemicals to pass through the cell membrane when it’s cold, sending an ‘ow!’ signal to the brain.

These proteins might also be involved in signalling prolonged pain and might act as a sensor of oxidative stress during inflammation, according to the study authors.

It could be possible to develop drugs that block this cold sensing pathway, thereby treating dentin hypersensitivity and inflammatory tooth pain, the researchers said.

“Oil of cloves’ (Syzygium aromaticum) main ingredient, eugenol, has been used for centuries as an analgesic in dentistry and inhibits TRPC5 currents,” the authors said.

“Once you have a molecule to target, there is a possibility of treatment,” said electrophysiologist Katharina Zimmermann, who led the work at Friedrich–Alexander University Erlangen–Nürnberg in Germany.

Science Advances 2021, 26 March

If you see something stupid, say something stupid … Send frosty story tips to felicity@medicalrepublic.com.au.