It depends what you're measuring.

Amid Victoria’s worrying COVID outbreak, perhaps the point of greatest concern is the fact the virus has again found its way into aged care.

On Sunday, the state government announced an aged-care worker had tested positive for COVID-19, despite having received their first vaccine dose on May 12.

We’ve since found out another staff member, who worked alongside the original staff member at Arcare Maidstone, has returned a positive result, along with a resident.

The resident had received a first dose of the Pfizer vaccine and reportedly has only mild symptoms, but is being monitored in hospital. The original worker’s son has also tested positive.

The cases in the first staff member and the resident, both of whom had received a first vaccine dose, highlight the fact you need both doses for maximum benefit.

It takes a couple of weeks

Clinical trials show COVID vaccine protection is optimal from about two weeks after your second dose. This means they:

- nearly completely protect against severe disease and death in healthy people

- dramatically reduce the likelihood of symptoms with COVID-19

- reduce the likelihood of infection with the virus

- if you do get infected, they reduce the amount of virus you make. Emerging evidence suggests this reduces the likelihood you will pass the virus to other people.

Each dose of a vaccine essentially shifts the odds in your favour. One dose gives you a lower chance of reaping some of these benefits, while two doses gives you a much higher likelihood of these benefits.

Though even with two doses, you could still be unlucky and get infected, develop disease or pass on the virus.

What do we know about a single dose of Pfizer?

Clinical trials of the Pfizer vaccine were designed to test the efficacy of the vaccine more than one week after the second dose. However, these trials also provided the first hints that a single dose could offer some protection as early as 12 days afterwards.

“Real world” data now supports these early observations — a single dose is highly effective against hospitalisation four weeks after vaccination.

Meanwhile, early research and reports suggest a first dose of Pfizer could be between 50% and 90% effective at preventing infection.

Preliminary data also suggest people who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 after one dose of the Pfizer vaccine are up to 50% less likely to transmit that infection to other members of their household.

Read more: Mounting evidence suggests COVID vaccines do reduce transmission. How does this work?

And what about a single dose of AstraZeneca?

The AstraZeneca vaccine was initially developed as a single-dose vaccine, estimated to have an efficacy of 76% against disease in clinical trials.

These trials were later amended to include a second dose when other work showed two doses significantly increased antibody levels in volunteers.

Real-world data, though yet to be peer reviewed, has shown one dose is roughly 65% effective at protecting from infection and up to 50% effective at preventing vaccinated people from passing the virus on if they do become infected, like Pfizer.

Also similar to Pfizer, a single dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine offers very good protection against hospital admission four weeks afterwards.

What takes so long?

Despite differences in mRNA vaccines like Pfizer and viral vector vaccines like AstraZeneca, both take similar amounts of time to generate antibody responses. After a single dose of AstraZeneca, antibodies can be detected after 14 days and further increase over the next two weeks.

But why does it take time for these responses to develop? When researchers track the antibody response to the first dose of vaccine, they find it takes at least ten days for the immune system to start making antibodies that can recognise SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein (a protein on the virus’ surface which it uses to enter our body’s cells).

It also takes at least a week for T cells, a type of white blood cell important in our immune response, to start to react to the vaccine. Over the next few weeks, these responses become even stronger.

Read more: What’s the Valneva COVID-19 vaccine, the French shot that’s supposed to be ‘variant proof’?

In contrast, the second dose activates the immune system much more quickly. Within a week of dose two, your antibody levels increase by more than ten times, providing much stronger and longer-lasting protection from infection.

So the first dose of a COVID vaccine gets your immune response going, but the second dose is essential to ensure immunity is strong, consistent from person to person, and longer-lasting.

Partial vaccination can be risky

While a single dose of either vaccine provides some benefits, relying on partial vaccination for people who are vulnerable or working in high-risk roles is problematic. It’s critical we fully vaccinate frontline health-care workers, quarantine workers and people who work and live in aged and disability care as soon as possible.

Another challenge is that all current COVID vaccines are based on the original virus strain but variants now make up the majority of infections in many countries. Some variants are targeted less effectively by vaccines, particularly after only one dose.

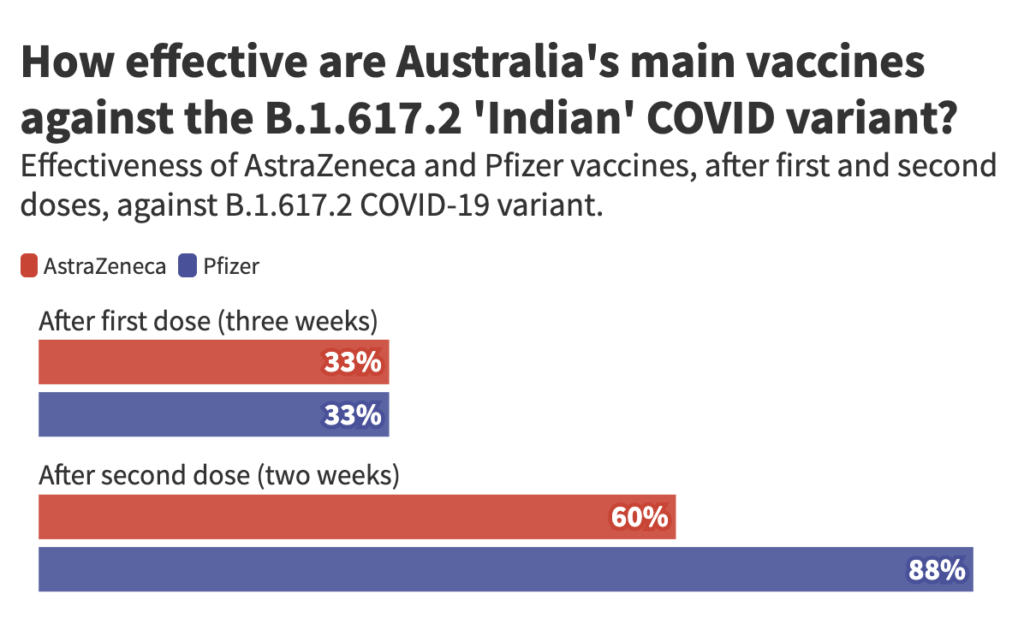

Preliminary data suggests that while two doses of the Pfizer vaccine are 88% protective against symptomatic infection with the B.1.617.2 variant, a single dose is only 33% effective.

A similar variant, called B.1.617.1, is behind the current outbreak in Victoria and may respond similarly. This makes it even more important to ensure frontline workers receive both vaccine doses as quickly as possible.

It’s also worth noting immune responses to one dose of either the Pfizer or AstraZeneca vaccines decrease with age.

In a pooled analysis of Pfizer and AstraZeneca, older people had lower rates of protection than younger people after a single dose, although older people were protected just as well as younger people after two doses.

Although this study is yet to be peer-reviewed, it tells us administering the second dose in a timely manner is particularly important for older people to realise the full benefits of vaccination.

Kylie Quinn, vice-chancellor’s research fellow, School of Health and Biomedical Sciences, RMIT University

Jennifer Juno, senior research fellow, The Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity

This article was originally published at The Conversation