The consultancy was funded to start a private digital platform company then contracted to write governments’ digital mental health strategies.

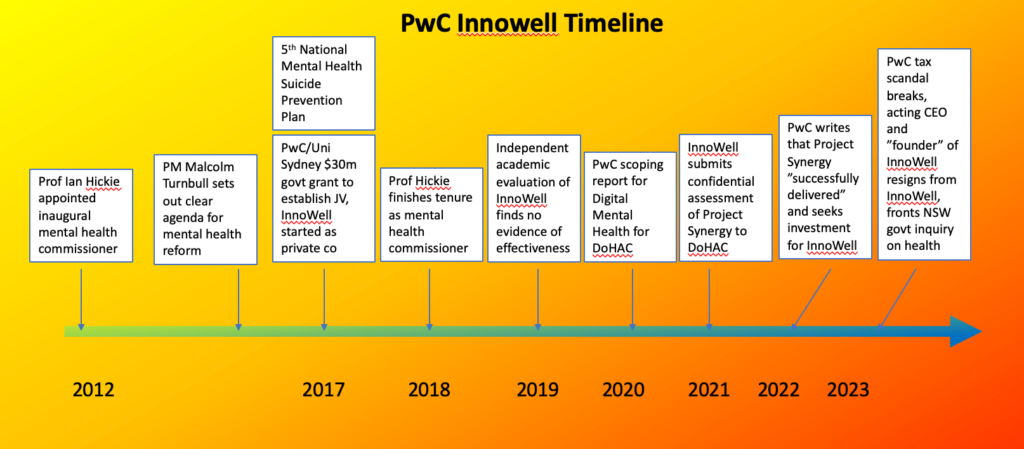

PwC Australia, in partnership with the University of Sydney, used $30m in government funding to develop a private, commercially run, mental health software company in which it had a 45% shareholding (now 32%); was contracted by that company to provide it ongoing services; and subsequently was contracted by the Department of Health and Aged Care to develop a digital mental health framework for Australia and a digital mental health strategy for the Victorian government.

In both the federal and Victorian government digital mental health strategy assessments written by PwC, the company – InnoWell, of which PwC was a shareholder – either featured formally in the narrative, or was aligned tightly to how PwC was recommending each government body view and roll out digital mental health strategies.

That PwC had received $30m in funding to develop a private venture in which it had a significant shareholding was not declared anywhere in a scoping report on digital mental health written for the federal government by PwC and paid for by DoHAC, nor in many articles that PwC itself wrote about digital mental health and InnoWell on its own website over the last five years.

In the PWC scoping paper a digital mental health service is defined as “a mental health, suicide prevention or alcohol and other drug service that uses technology to facilitate engagement and the delivery of care.”

In the final government positioning statement on digital mental health for Australia, nowhere is it declared that PwC provided a scoping consulting paper which formed much of the basis of the statement, or that the government had provided PwC $30m in funding to build a private software company in the space, prior to contracting PwC to do this work.

DoHAC told TMR that prior to commissioning PwC to do the scoping paper on digital mental health, PwC declared its relationship with InnoWell and this declaration was “assessed and managed in accordance with the Commonwealth Government Procurement Rules and Guidelines”.

Notwithstanding, the relationship was not declared in either the PwC scoping paper, or the final government positioning statement on digital mental health for Australia.

A PwC spokesperson told TMR that “PwC made the appropriate disclosures, in writing, as part of our proposal for the scoping and development of the framework. The final framework is a government document. It is not PwC’s role or place to have any visibility in that report.

“Furthermore, we have not ever sought to hide our involvement with InnoWell, including on our website.”

In various articles written by PwC, it boasts that it has secured $30m in funding from the government for a “collaboration” between them, the government and the University of Sydney to conduct trials in the mental health space, but in all the articles on mental health and InnoWell featured on their website there is no declaration that PwC had a 45% interest in a InnoWell or that the $30m in funding was being used for a set of trials designed to prove out the software product of InnoWell.

In late 2019 an independent academic report found that there was no evidence that the trials, for which the $30m funding was primarily used, proved that the software platform being built by PwC and the University of Sydney was effective.

But PwC subsequently publicly stated on its own website that the trials were “successfully delivered” to the point where its software product was now being commercialised and that they were seeking investment partners.

During all this time PwC had directors who were on the board of the InnoWell who were involved heavily in the running of the digital mental health and wellbeing business unit at PwC.

When it was revealed in the NSW government’s Use and Management of Consultant Services review this week that around 660 PwC consultants were sitting on about 990 company boards across Australia, inquiry chair Abigail Boyd suggested that PwC had a deliberate strategy to spike boards of companies with its consultants in order to manipulate those companies towards taking PwC work, including government work.

“[It works by] first of all, redesigning a health structure – which I know PwC had had quite a hand in – to devolve it into this board structure, to then put consultants onto boards, who are then critical in terms of giving work to other consultants while on those boards, building that relationship and then having a steady flow of income once they go back to their practices,” Ms Boyd suggested to PwC acting CEO Kristin Stubbins.

Ms Stubbins rejected this notion, telling the inquiry that “I sought to take an unpaid position as a board member because I thought I could do some good with my financial expertise for the taxpayers of NSW.”

But the inquiry also heard that Ms Stubbins herself had been on the board of South Eastern Sydney LHD, which subsequently awarded PWC a contract.

When questioned about this Ms Stubbins said she had resigned from the board of SESLHD when this happened to avoid conflict. However, minutes of the SESLHD record Stubbins as being present at board meetings and on subcommittees after it was agreed that she would resign.

Until June 5 this year, Ms Stubbins was the chair of InnoWell, meaning that she was chair during the period in which PwC was contracted by the federal and Victorian governments to write strategy on digital mental health.

To reiterate, both PwC and DoHAC confirmed that the potential conflict of interest relating to InnoWell was declared by PwC in a proposal to the department before it was awarded the scoping job.

Ms Stubbins still lists herself as a founder of InnoWell on her own LinkedIn profile and is described as a founder of the company on PwC’s website, where there are several references to the work done by PwC in the digital mental health space, but no mention of PwC’s shareholding in InnoWell.

She resigned as chair of InnoWell on 5 June but there has been no public explanation from InnoWell or PwC as to why she resigned.

PwC told TMR that Ms Stubbins stepped down from the InnoWell board when she was appointed acting CEO, given that it was a challenging period for the firm.

PwC’s website features several articles promoting the concept of digital mental health over the past five years, including updated assessments of the concept and its elevated importance during and post Covid 19. None of these articles specifically declare that PwC owned 45% of InnoWell.

In these articles PwC does state that it has a “$30m collaboration” with the University of Sydney and the Commonwealth government to develop a digital mental health platform and that it had helped develop a commonwealth framework and Victorian government strategy on digital mental health.

In some of these articles PWC uses InnoWell as a case study of the potential of using digital mental health platforms, but again, there is no specific declaration that PwC has a 45% shareholding in InnoWell.

PwC’s shareholding in InnoWell has always been publicly available through ASIC since the formation of the company. Today its shareholding is 32%.

TMR is not suggesting that anything that PwC, the University of Sydney, DoHAC, or any other shareholders InnoWell has done is illegal.

Other shareholders of InnoWell include Professor Ian Hickie, head of the Brain and Mind Centre (BMC), a network of researchers and clinicians operating out of the University of Sydney in the area of mental health.

Sydney University says in an article on its website about Project Synergy (the trials component of proving out the InnoWell platform for which most of the $30m in funding was awarded) that it subcontracted the Brain and Mind Centre as one of the major providers of services to InnoWell.

There is no publicly available reporting of how the $30m in commonwealth funding was spent by InnoWell, though it appears that at least $1.5m of the money was spent early on in the venture on an office fitout. Innowell declined to provide any of the detail when asked last week.

The fitout contract was a won by Buildster and advertised by that company in late 2017.

Buildster described the contract as follows:

“Integrated full fitout and procuring of all furniture, graphics and joinery. Complex and state of the art AV and data installations. New fit out of all DDA, toilets, ceilings, carpets, doors and sound walls. Buildster was given one-week lead in with an extremely fast 8-week construction program.”

It is believed that most of the $30m in funding was spent on 13 trials for Project Synergy from 2017 to 2019.

NHMRC funding records show that Professor Ian Hickie won an additional grant of more than $3.4m for the BMC in 2020 to conduct a “large-scale clinical effectiveness (health services) trial to determine whether personalised health care packages, combined with digitally supported measurement-based care, improve functional outcomes in young people with mood disorders”

By the time this NHMRC funding was awarded to the BMC, it is believed that PwC and Sydney University had already spent most of the $30m on 13 clinical trials and that those trials had been assessed independently at the end of 2019, as at that point of time at least, as not showing any meaningful results which could determine the value of the platform (see below).

Professor Hickie was recently embroiled in a bitter dispute with the GP sector after he accused GPs of not reviewing mental health plans properly and blocking access to mental health care by refusing to bulk bill for mental health items.

At the time RACGP president Adjunct Professor Karen Price said that Professor Hickie fundamentally misunderstood how GPs worked with their patients on mental health and was conflicted by his involvement on various government mental health reviews.

“Professor Hickie is clearly pushing his own agenda while he is advising the government’s review of the Better Access Scheme for mental health,” Professor Price said.

Professor Hickie is listed as a 3.2% shareholder of InnoWell today but originally had a 5% holding in the company.

The 2019 independent academic report commissioned by InnoWell to assess the effectiveness of Project Synergy Trials and the InnoWell platform, asked four specific questions for which the investigators could not provide any definitive answers:

Using a co-design approach, to what extent has Project Synergy enhanced mental health service access and quality?

To what extent has an impact on the everyday lives of people with lived experience of mental ill health using InnoWell Platform-enabled services been observed?

To what extent did Project Synergy provide learnings that have informed and influenced policy and practice in mental health services.

To what extent has an impact on the everyday lives of people with lived experience of mental ill health using InnoWell Platform-enabled services been observed?

Here is some of what the investigators said about the trials and the platform in the context of these questions:

- evaluation participants suggested that clinicians were not using the Platform as much as anticipated, with many suggesting that the Platform was a significant cultural shift in the way front line staff worked.

- Some participants in the evaluation also had concerns about the tone of the Platform appearing to be more problem than strengths focused, and that negative feedback might be demoralising to some users.

- The number of clinicians and consumers using the Platform was reported anecdotally as low.

- While figures are available on its use for each trial site, they are difficult to interpret without understanding the capacity of the service to take on new consumers, how the service tried to engage consumers to use the Platform, the number of consumers and clinicians invited to use the Platform, and the expected uptake.

- Despite the lower than expected number of consumers using the Platform at the trial sites included in this evaluation, the Platform data shows attrition of users between the time of invitation, registration on the Platform (in some cases as links expired), and then completion of the different assessments required.

- It is difficult to ascertain user experience of the Platform as, at the time of reporting, there were no feedback mechanisms for users to share their experience.

- The Platform has had a mixed response particularly by practitioners, many of whom have, at least initially, perceived it as adding another administrative burden to their work.

A key finding of the investigators was that “in terms of consumers, the evaluation was not provided with sufficient data to draw any conclusions about the value to their treatment and their outcomes”.

Another key question that InnoWell asked the independent investigators to assess was how well Project Synergy and InnoWell aligned with government policy on mental health:

To what extent has Project Synergy maintained alignment and consistency with the broad mental health policy agenda and context?

The independent evaluation team found the project to be highly aligned with our health policy agenda.

Professor Ian Hickie was at the centre of developing government policy on mental health in most of the years leading up to the awarding of the $30m grant as the inaugural commissioner of mental health, a position which he served from 2012 to 2018.

And as described above, PwC helped write the digital mental health framework for the federal government and Victorian government.

The original $30m grant to PwC and the University of Sydney was awarded in 2017.

The independent academic report does not note the involvement or shareholding of PwC.

This report appears to have formed the basis for a separate report prepared by InnoWell itself for DoHAC which was submitted to DoHAC July 2021.

This document appears to have been kept confidential by DoHAC until it was the subject of a Freedom of Information request and released in May this year.

This document does not contain any of the more pointed conclusions of the independent academic report commissioned by InnoWell around effectiveness of the Innowell platform that suggest that both Project Synergy and InnoWell had not, until that point in time, generated any data which proved the InnoWell platform was working.

However, like the independent report,the InnoWell report to DoHAC does not provide any evidence or commentary t Project Synergy or InnoWell had been successful either.

Based on this report it is likely that by mid-2021 the federal government knew that most of its $30m had gone and there was so far nothing to show for it as there was no evidence that InnoWell was working.

There was no reporting of the progress of either Project Synergy, the grant or InnoWell by the government after they received this report and the InnoWell report remained confidential from June 2021 until May this year when it was released as a result of an FOI request.

PwC delivered its Scoping of a National Digital Health Framework for the federal government in November 2020 after the independent academic report had shown no evidence of InnoWell working in the community.

None the less, the scoping report promotes the sort of technology that InnoWell was trying to develop, and Project Synergy was trying to prove out, as part of a broader ongoing solution to mental health issues facing Australia.

Again, there is no acknowledgement by DoHAC in this report that PwC owned shares in a company that was trying to build a mental health software platform that aligned to the strategy that was being recommended in the report as one of the ways forward for government policy.

In an article written about corporate digital mental health which featured InnoWell by PwC in May 2022, it is claimed that trials funded by the $30m government grant to PwC and Sydney University to prove out the validity of the InnoWell platform had been “successfully delivered” and that the platform was moving into an active phase of commercialisation and more investment.

This article was written more than two years after InnoWell had received its independent academic review of Project Synergy and InnoWell indicating that there was, at that point of time, no evidence it was working, and after InnoWell submitted a watered down version of that report to DoHAC.

The PwC article reads:

“[PwC] worked together to obtain a $30 million grant from the Commonwealth Government to deliver 13 clinical trials to develop a practical technology solution to help people with mental health issues. Those clinical trials have all now been delivered successfully and we have been commercialising the InnoWell platform. We’re now moving into the next phase of our development, attracting external investment and offering clinical practitioner assisted care to a number of clinical organisations and self managed mental fitness support to organisations such as those you might be on the boards of.”

This article appears to be spruiking the InnoWell platform to board members of corporate clients.

Neither PWC would confirm who was now investing in the Innowell platform, or, who is even using it still.

Listed as contributors to the session from which this article is developed are Dr Sharon Ponniah, PwC Health and Wellbeing Partner and national lead for Mental Health and Wellbeing; Ms Stubbins [now acting CEO], PwC Executive Board Member, Chair Mental Health Board; Tuanh Nguyen, PwC Director, Diversity & Inclusion Consulting; and Nicola Lynch, PwC Health Assurance Lead Partner.

InnoWell has never produced any public reporting that suggests that all its trials were successfully delivered and its initially confidential report to DoHAC, provides no commentary suggesting the trials proved the integrity of the InnoWell platform, as is this PwC article seems to suggest.

TMR has knowledge of one Project Synergy trial for which there were no firm conclusions made as to the integrity of the InnoWell software (consistent with both the independent academic investigators report and the InnoWell report to DoHAC) and for which no further development of the trial learnings were put into practice in the trial location or in any other similar clinical setting.

One person involved in running this trial said that the Innowell platform did not work, and that in certain situation it might even be “dangerous”.

InnoWell would not confirm if any of the trial sites had gone on to purchase and use the InnoWell platform in Australia

The platform appears to have been sold into Alberta Health Services, a regional government health provider in Canada, and according to its website it is in use today for managing youth mental health.

Independent business reporting sites estimate that the revenue of InnoWell is only $4m per year or less. On LinkedIn, only 20 people are listed as being employees of InnoWell.

TMR asked InnoWell the following questions:

- Was the $30m in grant money awarded by the department of health in 2017 used to set up InnoWell, or was that money exclusively for Project Synergy trials

- Where can we access reporting of InnoWell’s performance in terms of its revenue and profit, current contracts and ongoing viability? If it’s not available, can we please get comment from InnoWell?

- The UNSW academic assessment of Project Synergy commissioned by InnoWell in 2019 found no evidence that the InnnoWell platform was effective or ineffective either way, but there were various issues about being able to assess its value which came out in that report. Is there any other assessment that or follow up trials that indicate InnoWell is generating good outcomes for clients? Is the product commercially viable?

- Does InnoWell have ongoing contracts with any of the clients that initially trialled it? If not, who is using it in Australia and are these commercial deals?

- Is it being used still in Alberta, and has it been sold anywhere else in the world?

- Can we confirm that InnoWell is a private company that, should it be successful, shareholders can expect to profit off?

- Can we get comment on whether there was any perceived conflict of interest at InnoWell’s end in regards to PwC receiving a government contract to write the national digital mental health strategy scoping paper and the Victorian digital mental health strategy? We’re curious given the fact that the consultancy firm did this while owning a private shareholding in a company that theoretically stands to benefit from the strategy they are advising on.

- Can we also get comment on whether InnoWell believes PwC should have declared its interest in InnoWell somewhere on the national digital mental health scoping paper it wrote for the department of health?

This is the statement we received in response, in full:

“InnoWell is proud to support our clients’ continued effort in the care of individual’s mental health needs.

“The successfully delivered clinical trials during Project Synergy showed an overwhelming support for integrating digital health solutions into mental health service settings.

“One client’s most recent success includes reducing wait times by up to 60%, showcasing improved mental health outcomes with the InnoWell platform.

“We will continue to provide the technology and support our clients through the change process to focus on the maintenance of good mental fitness and the treatment of mental illnesses in our communities. We believe the world works better when people’s individual mental health care is supported with the right tools at the right time.”

We put similar questions to Professor Hickie but he deferred to Innowell to answer the questions.

There is no information as to whether any of the original funding for Project Synergy is left or if InnoWell is generating enough revenue to keep it viable.

PwC continues to promote the company to potential investors via its website.