Should mental and emotional illnesses be lumped together? asks Dr Christine Adams

When a person gets depressed over their divorce, they are said to have a mental illness.

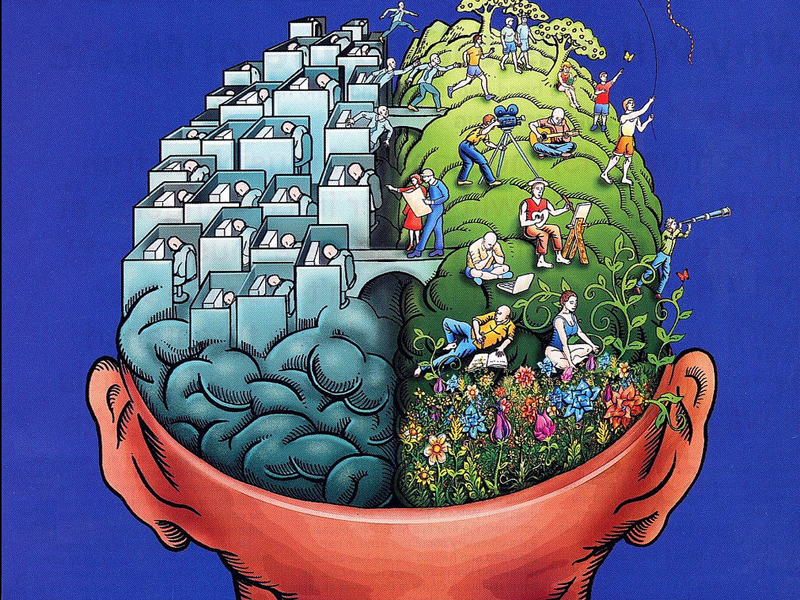

When a person becomes psychotic from a manic episode due to their bipolar disorder, they are also said to have a mental illness. But are both of these illnesses mental illnesses? The definition of mental is that which relates to cerebral, brain, cognitive or intellectual processes.

Many disorders occur from problems in the anatomy or function of the brain: epilepsy, tumors, agenesis of a brain area, strokes, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, autism, Alzheimer’s and Tourette’s disorder, to mention a few. These disorders can affect memory, thoughts, perceptions, emotions, and movements. Most of these problems or illnesses are called neurological disorders. But some are called psychiatric disorders.

There is also a third category, the non-brain-based emotional disorders such as depression, panic, anxiety, anger, substance abuse and obsessions. These are not caused by brain malfunction or anatomical anomalies. They are caused by our relationship problems with people we live with, associate with, and work with.

Don’t we all have emotional distresses and problems at times due to interpersonal strife? Don’t some of these become emotional illnesses? We all have relationship conflicts of varying degrees that cause us at times to feel depressed, anxious, angry, or sad. When these problems with our mates, children, co-workers, bosses, friends or relatives become severe, then we have emotional illnesses that require treatment.

But, under what circumstance will most people seek treatment? When they are told they have a mental, i.e., brain, illness? Or, when they are told they have an emotional illness that can be more common and which does not mean there is anything wrong with their brain but only that they have some problem in their relationships that requires better understanding and psychotherapy as their treatment?

Stigma is defined as “an association of disgrace or public disapproval with something, such as an action or condition.” We regard mental illnesses with stigma. And, because we do many people do not seek treatment for fear of this stigma and discrimination. Such discrimination does occur worldwide. Why do we do this?

My impression is that part of mental illness stigma exists due to psychiatry calling both emotional and mental problems mental illnesses. With mental illnesses, people know that something is wrong with their brain. Their concern is that their identity is uncertain since who they are is sick. This causes enormous distress. With emotional illnesses, something is wrong with how people manage relationships. Brain pathology problems are scary. Relationship pathology is not so terrifying.

Actual psychiatric mental illnesses of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia have a low incidence over centuries (about 1.1 percent for schizophrenia and 2.6 percent for bipolar disorder). They require medications, mood stabilizers, and antipsychotics, along with psychotherapy. Yet 26.2 percent of American adults have a diagnosis of mental illness. It appears that the remaining 22.5 percent of these illnesses are emotional illnesses that are lumped in with the mental illness category.

If psychiatry would quit lumping the more frequent (22.5 percent) emotional illnesses in with the less frequently occurring (3.7 percent) mental illnesses, many more people might seek treatment. They just might feel freer to seek out treatment and do it sooner for the common emotional illnesses they share with their neighbors’ friends, family, postman, and barber. They might be glad to know they do not have a brain problem.

For most people when they break their leg they have no compunction in visiting an orthopedist to set their leg. Shouldn’t psychiatry urge the larger number of people with emotional illness to treat their relationship problems by a trip for psychotherapy?

Please let’s quit lumping mental and emotional illnesses together. Psychiatry confuses people when it lumps the two. Perhaps by doing so, we can do away with some stigma. Wouldn’t it be great if psychiatry quit looking for emotional illnesses in the brain and helped people understand that relationship distresses can exist free of brain pathology? Our brains process everything in life that we experience, but that is not the same as having a brain problem. Emotional illness arises from the people we live with, associate with, and work with and how we manage our relationships with them.

Christine B. L. Adams is a child and adult psychiatrist. She can be reached at her self-titled site, Christine Adams, M.D.

This blog was originally published on Kevin MD.