Doctors’ professional values play a role in whether they develop post-traumatic stress disorder

A study of medical staff at a military field hospital in Afghanistan suggests doctors’ professional values play a role in whether they develop post-traumatic stress disorder

The researchers looked at surgical staff at the British-built Camp Bastion Field Hospital in Afghanistan’s Helmand Province, and concluded professional expectations influenced whether people were traumatised – not just supposedly universal triggers such as exposure to the cruelty and horrors of war.

Repeated experiences of senselessness, futility and surreality were particularly distressing for the mostly British and US doctors, according to the study by Australian and British academics.

“(It was) difficult for them to come terms with rules, practices and experiences on the ground that appeared contradictory to their purpose and values, thus amplifying feelings of senselessness,” the study says.

Doctors were upset that their 50-bed field hospital required quick transfers of badly mutilated children and other Afghan civilians to inferior local hospitals, often within 48 hours, to make way for battlefield casualties.

They spoke of the “frustration of bringing a stable, anaesthetised patient over to some hospital only to be met by an empty van, having to hand over a wired-up patient to someone with no equipment at all”.

The surreal nature of events also took a toll.

A theatre nurse related carrying a severed human leg in a bucket to the mortuary, and encountering his commanding officer and another nurse carrying Easter eggs and wearing bunny ears.

Over time, the disorienting effect of the grave human situation amid casual everyday routines can damage a person’s ability to find meaning in ordinary events in life back home, the study says.

“The study highlights the urgent and serious nature of dealing with PTSD – beyond the very real impact on many veterans, to others who work in the theatre of war, such as medical personnel,” said co-author Jaco Lok, of the UNSW Business School.

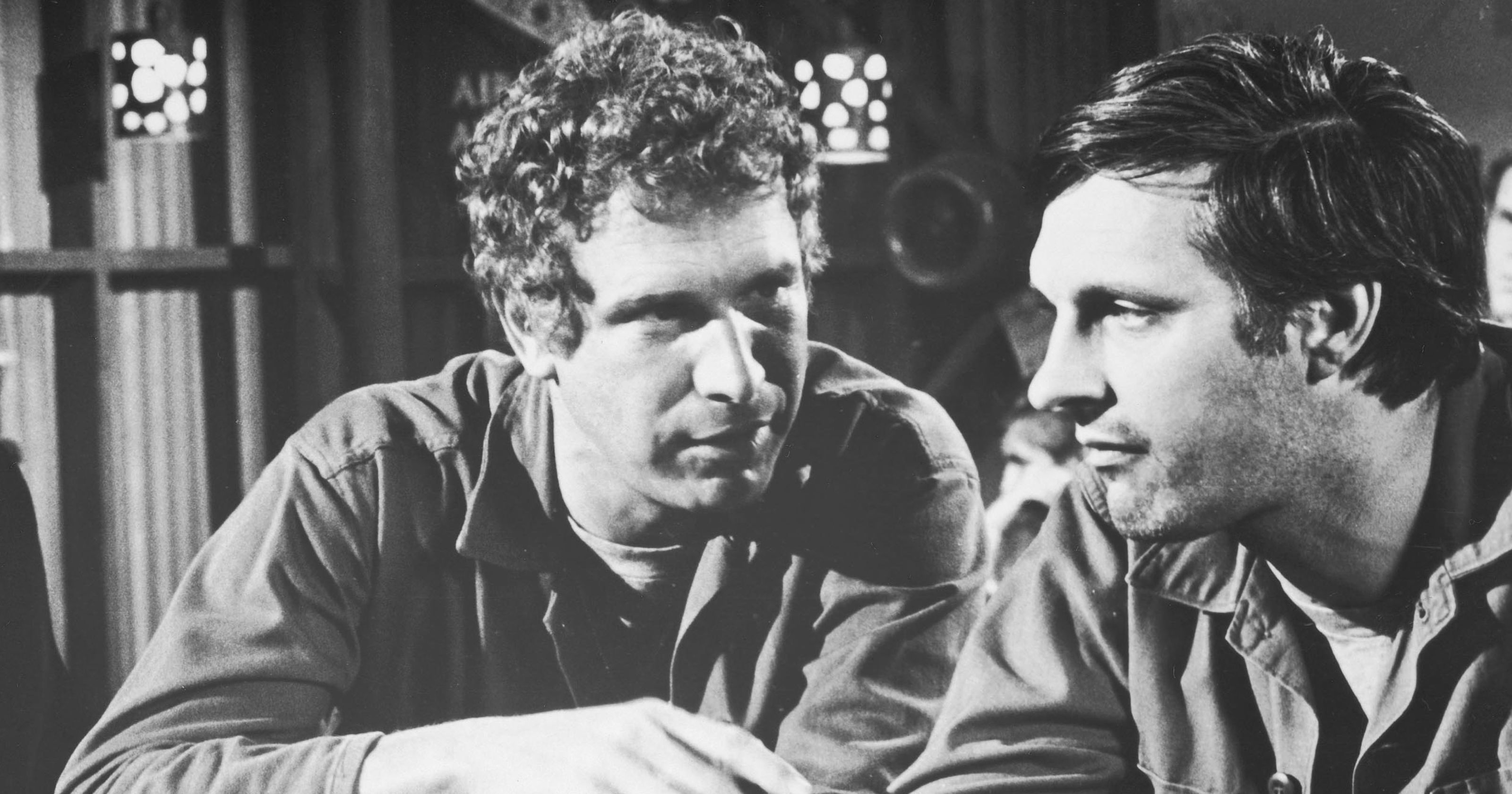

The study was based on fieldwork by ethnographer Mark de Rond, of the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School, who was embedded at Camp Bastion in 2011.

“The doctors I was embedded with were known as Rear Located Medics, who don’t have a combat role, so they have less reason to fear for their lives than frontline personnel,” the British academic said.

“Studying this group was an excellent way to look beyond psychological reaction to the horrors of warfare in order to analyse contextual elements that lead to PTSD.”

Deeper understanding of the connection between PTSD and the context of those who suffer from it could change the way mental health experts analyse, prevent and manage psychological injury from warfare, he said.

The study – titled “Some Things Can Never be Unseen: The Role of Context in Psychological Injury at War” – was published in the UNSW Academy of Management Journal and featured in the August edition of the online journal Business Think.