Exclusive: Australian police have been quietly requesting thousands of private medical records for years, with very few restrictions

The Department of Human Services has decided to release the guidelines governing the disclosure of private health data to the police, one year after rejecting a Freedom of Information request by The Medical Republic.

The thought of the police rifling through private health documents makes many Australians feel uncomfortable, as evidenced by the furore surrounding access to the My Health Record, but our investigation has revealed police can access other private health data relatively easily through the department.

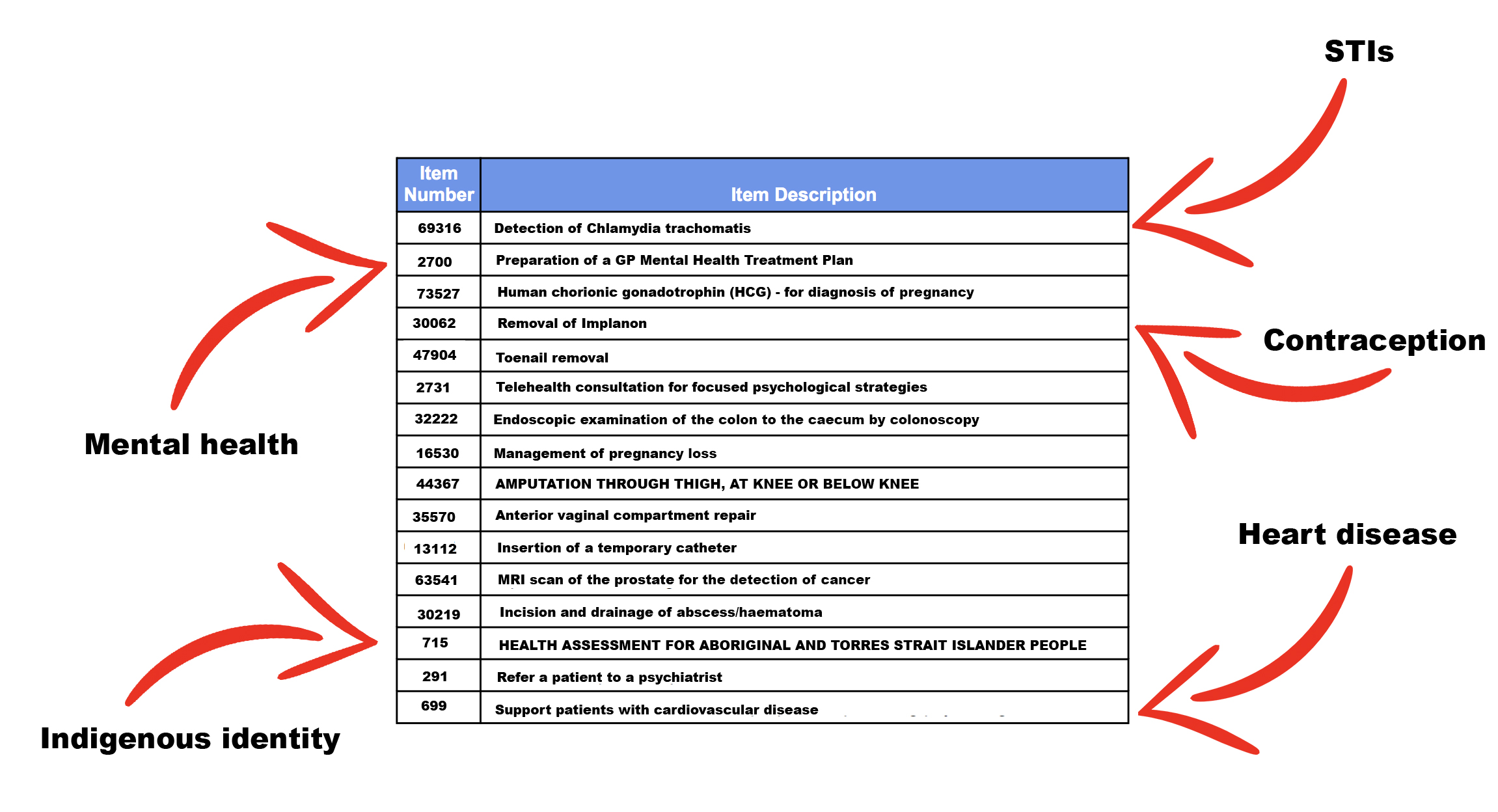

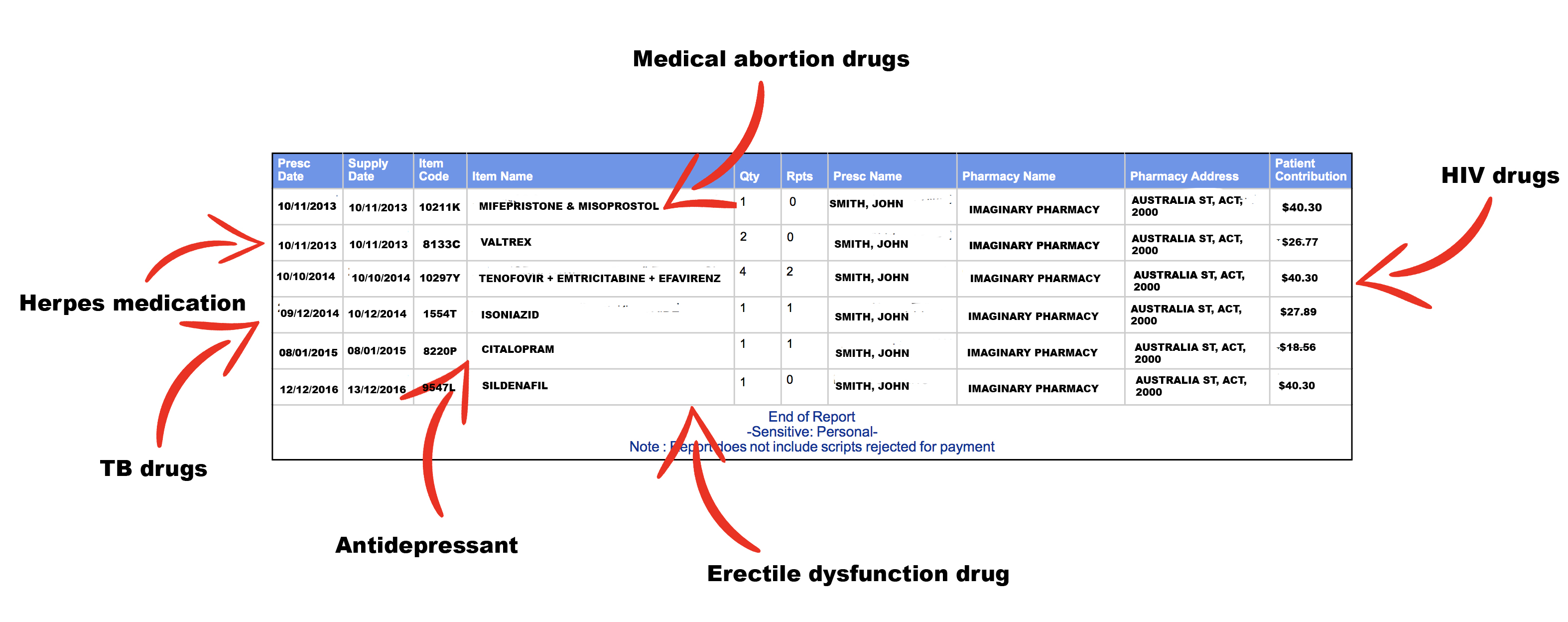

The data held by the Department of Human Services is just as sensitive as My Health Record data, and can include information on abortions, mental health and STIs.

We know from a previous FOI request that state, territory and federal police request around 2,600 private health records every year from this department.

But, while the police need a court order to access My Health Record data, no court order is required to access health data held by the Department of Human Services.

Instead, department officials use a set of guidelines to adjudicate police requests for Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) and Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) data.

Health privacy advocates are uniformly unimpressed by the quality of the privacy provisions in the department’s guidelines.

“If the road to hell is paved with good intentions with this process the government has created a four-lane highway,” Peter Clarke, a barrister at Isaacs Chambers in Melbourne, said. “The process is the antithesis of proper privacy protections.”

Dr Bernard Robertson-Dunn, the chair of the health committee at the Australian Privacy Foundation, pointed out the department’s guidelines had not been updated in 16 years. “So much for taking privacy seriously,” he said.

We requested a copy of the guidelines under FOI laws last year, but the request was rejected by the department.

The Department has now decided to release the guidelines, one year after we asked the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner to review the decision.

This is the first time the public will have the opportunity to review the Guidelines for the release of information where necessary in the public interest, which were established by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing in 2003.

The document released to The Medical Republic by the department was mostly blank. Whole pages had been redacted because they fell outside the scope of the original FOI request.

The key paragraphs that could be read stated that releasing private health information was not a decision to be taken lightly.

According to the guidelines, department officials would have to consider whether the disclosure of private health data was necessary and not merely convenient or helpful. They would also have to check whether the information was available through other channels.

Department officials would have to consider whether releasing the private health information was in the public interest as distinct from any private interests of the person seeking the information.

In the guidelines, the “public interest” is broadly defined as anything relating to national security, major crime, the administration of criminal law, or public safety.

The guidelines gave some concrete examples of serious situations where disclosing private health data to police would be in the public interest, such as to assist with investigations into murder, abduction, sexual assault, child molestation, serious drug offences and major fraud.

However, the document also stated that “these examples are not to be read as in any way limiting the circumstances in which the release of information may be regarded as necessary in the public interest”.

Jonathan Crowe, a professor of law at Bond University, said the “broad and vague nature of the guidelines for releasing confidential medical data to police is highly concerning”.

“The definition of public interest is particularly open-ended and leaves significant and unchecked discretion to department officials,” he said.

Hank Jongen, the Department of Human Services’ general manager, said the department took its privacy responsibilities “very seriously” and complied with all the relevant legislation.

He said information on MBS and PBS claims “may be significantly less detailed than the type of information found on a person’s My Health Record” because it did not contain clinical notes made by health services providers.

MBS and PBS data are generally used as administrative records to keep track of government rebates to doctors and patients. But the nature of the information can be very personal, as shown in the examples below.

Privacy experts have called for the department’s privacy provisions to be brought in line with the My Health Record legislation.

The law was changed in 2018 so that the police could no longer access My Health Record data without a court order.

“I would have thought the law relating to access to MBS and PBS data should be updated to reflect the decision by the parliament on the My Health Record,” Malcolm Crompton, a former privacy commissioner of Australia and founder and lead privacy advisor at Information Integrity Solutions, said.

Dr Chris Moy, the chair of the ethics and medicolegal committee at the Australian Medical Association, said the department’s data privacy laws should probably be put to the “pub test” to see if they still met community standards.

You can view the heavily redacted guidelines here.