The callous culture in medicine can be debilitating. We are doctors too – that is, we are human, and sometimes fragile.

“Wherever the art of Medicine is loved, there is also a love of Humanity.”

– Hippocrates

Day 1 at a new hospital. Surprisingly, obtaining my ID card and sorting out parking happens smoothly. The hospital feels clean and organised, assuaging my nerves around another new start. I meet my new colleagues and feel confident about what lies ahead.

Day 2 at my new hospital – it’s mine already! How quickly we doctor-in-training chameleons adapt to our environment.

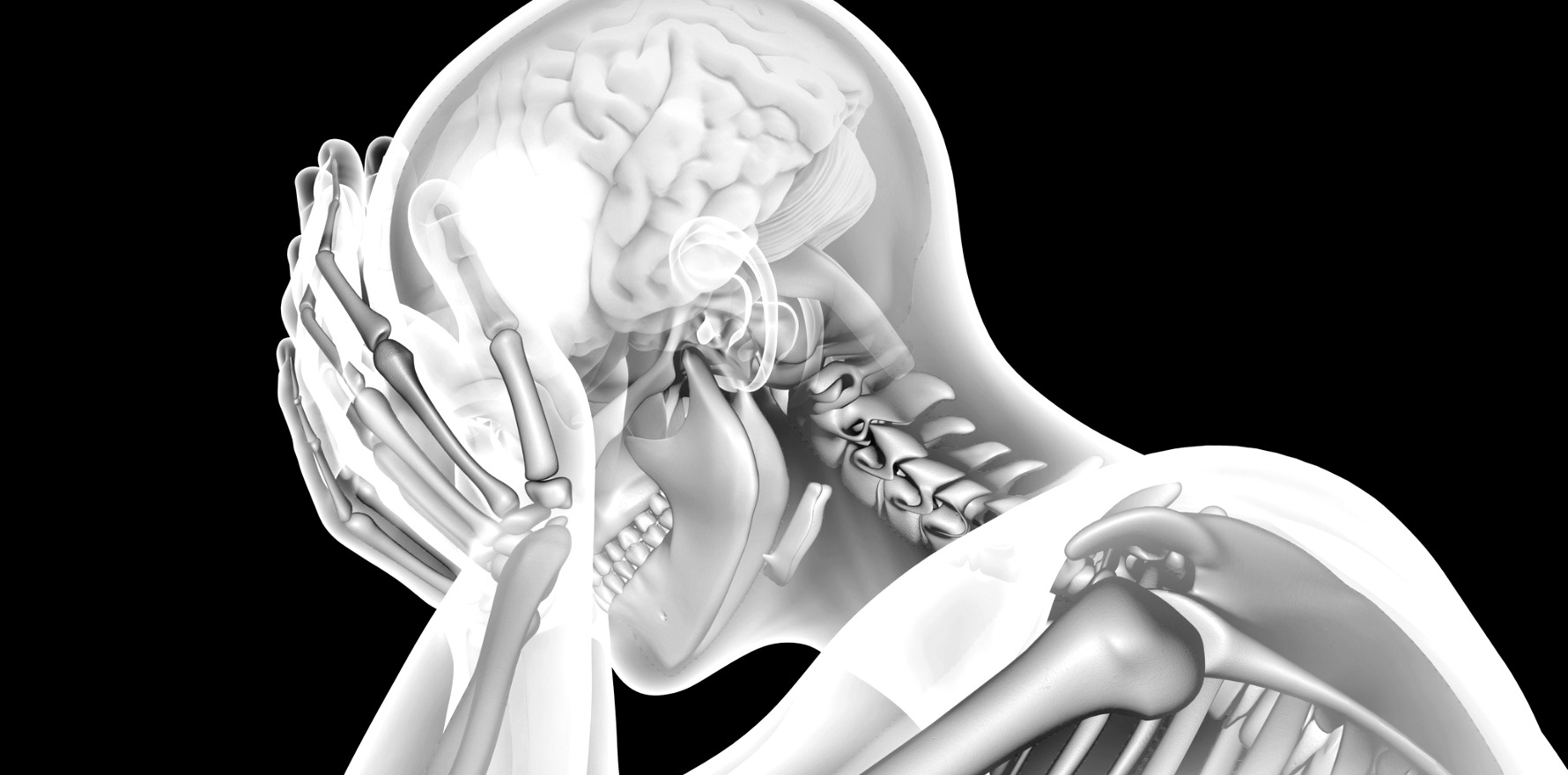

Already, though, today is different – a day spent holding the phone has led me to despair. To being literally curled up on the bathroom floor. How have I got here? How has four years of medical school, a research medical masters, a graduate diploma in medical leadership and almost seven years of clinical experience led me to this point?

Medical school is dimming into my distant past. When I think about those years, I remember my hopeful outlook and alternate between embarrassment, sadness, and wistfulness. Sometimes, I want to retrace my steps and choose something else. At other times I want to inject concrete into my veins, something that sets in the part of my brain that is too soft – the area that looks after my sense of self, my feelings of worthiness, usefulness and even my faith in my abilities.

In better times my resolve is clear: I want to change the culture of this amazing career path we walk down.

This is something I can control, and it’s why I have become an active member of AMA Queensland’s Council of Doctors in Training.

Over the years I have gained clinical skills, worked with busy teams, talked to patients and their families about so many different things. A good doctor in training is one who is organised and – one boss told me – one who never has to be asked to do something twice. They don’t trouble the boss about things they should know and know exactly when to ask about things they don’t. A good doctor in training always must consider the needs of everyone else on the team. It’s this last point that leads to many of us getting lost.

Each term our rosters are drawn up at the last possible legal moment. Sometimes they do not even make that cut-off. We have some protections, thanks to MOCA 5, but it’s not considered OK when you are part of a team not to do your share of out-of-hours work. Sometimes these hours are not registered with payroll for fear of upsetting your boss. Sometimes you are compelled to come in on your days off – to learn extra skills , perform extra jobs, to try and get ahead. No matter what your personal or family situation.

The system can be both egalitarian and ruthless. Applying for leave means holding your breath. Nothing is your own until you hold the hallowed title of Boss Doctor – or consultant. This can take between five and 15 years after completing medical school.

Being good at what we do is not enough. Study, research, try to find work-life balance, try to make friends, and have a social life, make sure you get enough sleep. Your family must make do with what is left.

On choosing my career I considered this – I thought that radiology would keep me in the hospitals, interested and with more control over my life than my alternative surgical pathway. That is not true and, worse, I didn’t factor in the phone calls.

After answering the phone on countless occasions that day I admit I had a small breakdown.

Every team has a phone. When the radiology registrar answers their phone, we sometimes encounter helpful doctors who are requesting a particular scan. Sometimes we even get the added thrill of being asked our opinion. Sometimes, though, we are told to arrange a scan. Sometimes we ask some clinically relevant questions and the scornful replies we may receive can be breathtaking. “Come and see the patient if you want to know.” “Because my boss wants it.” “Yes, the patient is stable and has a normal set of blood results but we just want to be certain we haven’t missed anything.”

On this occasion, after a long day of this type of phone call, coupled with my limited understanding of my new hospital’s systems, I could feel the bottom drop out of my doctoring career. Sometimes it feels that all those years I spent (and am still spending) studying and working are completely disregarded by those who should understand it best – fellow doctors.

I know this territorial mindset is not unique to radiology. I have heard ED doctors called triage specialists, surgeons dismissed as only good with their hands and physicians spoken of as unable to see anything of the patient outside their specialty.

Too often we don’t enquire as to our fellow doctors’ names – they exist only as the Surg Reg, the ED Intern, the on-call PHO. This anonymity feeds rudeness and disrespect.

It’s not always or even typically the case. The best doctors, the ones I would trust with my friends and family, treat other doctors with respect – or, when they are tired, stretched and uncertain and their manner falters, they acknowledge it. These doctors remember that fellow doctors have feelings and families and a large amount of knowledge which could benefit their patient, and themselves. They understand that some problems originate from and extend far beyond individual doctors – that our healthcare system requires radical disruption.

But, in the meantime, please, when you call radiology, remember we deserve as much respect as everyone else on your team. When you talk about your patients with us, remember we understand clinical presentations, examinations, anatomy and pathology as well as the physics and the limitations of our imaging studies.

Please, when you ring a radiologist, or any other member of our medical team, remember they are a doctor and a human too.

Dr Rachele Quested is a doctor in training, a mum of six, a try-hard triathlete and deputy chair of the AMAQ Council of Doctors in Training