A change in criteria for PCOS raises the issue of overdiagnosis for some women

A diagnosis of PCOS doesn’t encourage women to adopt a healthier lifestyle and may, in fact, lead to poorer adherence to contraceptives, a study of Australian women suggests.

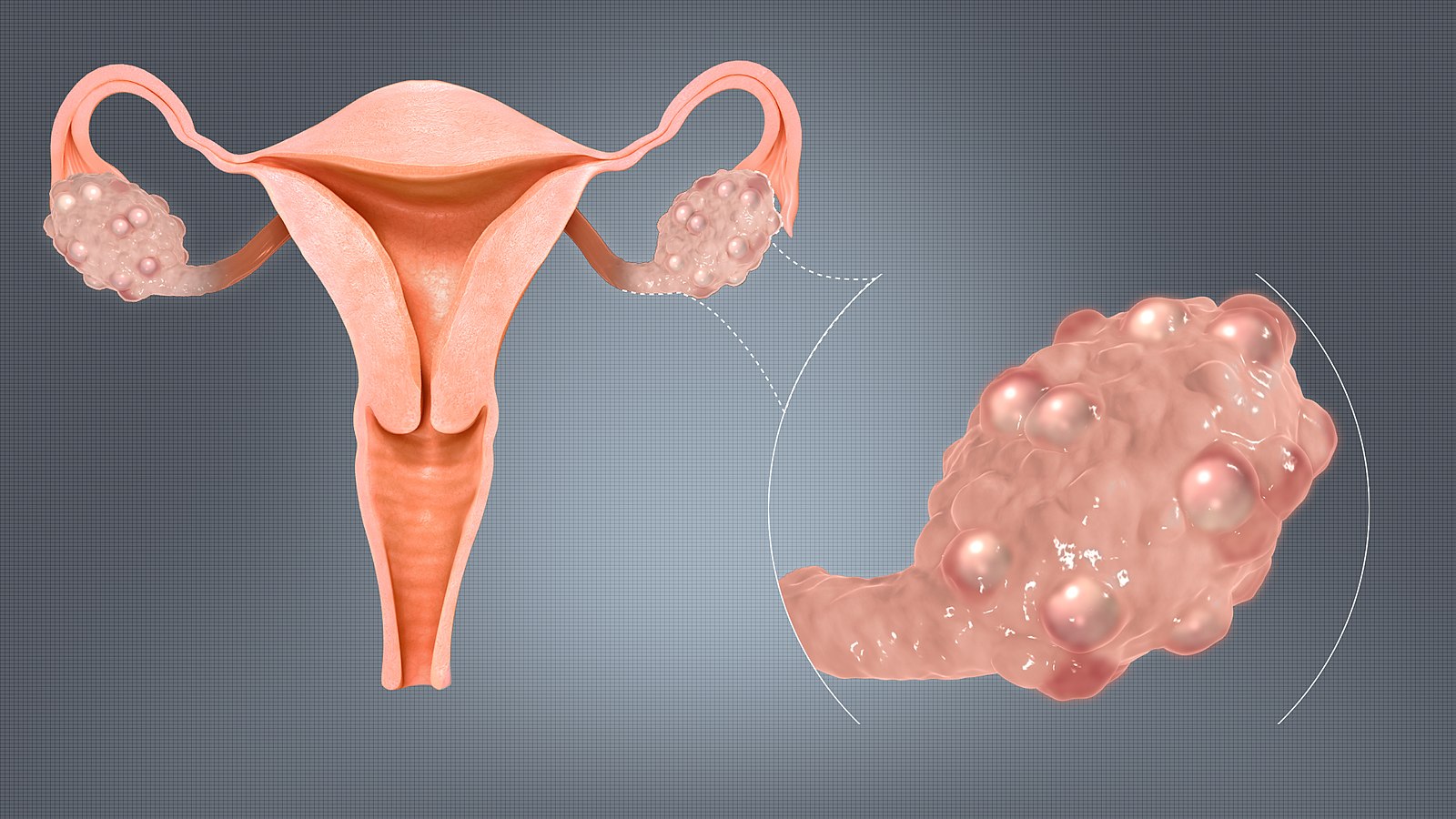

Concerns about overdiagnosis followed the adoption of the Rotterdam criteria, which labels women as having the condition if they had two out of the following three characteristics: irregular periods, elevated levels of androgens – seen in either acne, excess hair growth and hair loss – and polycystic ovaries on ultrasound.

By this criteria, as many as one in six women may have PCOS.

“Suggested benefits include the opportunity to initiate family planning and make healthy lifestyle changes to reduce the associated long-term risks,” says Tessa Copp, a PhD candidate at the University of Sydney. “However, there is no evidence of this, so this study aimed to investigate whether women’s health behaviour changes after being diagnosed.”

Ms Copp and her team analysed survey data from around 10,000 women participating in the Australian Longitudinal Survey on Women’s Health, which is a population-based cohort study.

The first survey data was from women aged 18 to 23 years, and the second wave of data was taken 12 months later.

They found that young women with a new diagnosis of PCOS were no more likely to exercise more or eat more vegetables than women without a PCOS diagnosis. Moreover, these women were 3.4 times more likely to stop using contraception over that year than women without the diagnosis (14% v 4%).

This gap was statistically significant, even when the researchers controlled for demographics and chronic conditions such as BMI, endometriosis and psychological distress.

“While a diagnosis may be motivating for some on an individual level, these results suggest a PCOS diagnosis does not lead women to adopt more healthy active lifestyles in the months following the diagnosis,” Ms Copp says.

Previous research by Ms Copp suggests that some women with PCOS try to conceive earlier due to their perception of their reduced fertility or take risks with contraception because they don’t think it is necessary to prevent pregnancy.

This is despite evidence indicating that women with PCOS have similar numbers of children to those without the condition.

“Unintended pregnancies can have an enormous impact on all aspects of women’s lives, so it is vital doctors reinforce the importance of using contraception for women who are not trying to conceive,” she says.

For women with severe symptoms, a diagnosis can validate and legitimise women’s symptoms, providing them with a label to describe their experience, says Ms Copp.

“However, women with minimal symptoms or an uncertain diagnosis may experience more harm than benefit, including long-lasting anxiety and altered life plans.”

For these women, symptoms can be treated and lifestyle advice given without the diagnosis, with clinicians mentally noting at risk and following up over time, she says.

“This stepped approach to diagnosis may be a way to optimise the benefits while reducing harms from disease labelling.”

The study relied on self-reported diet and exercise data, and only captured vegetable intake. It’s possible that changes occurred outside after the 12-month window or manifested in other ways not captured by these measures.

Human Reproduction; https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/dez274