Yes, puffers contribute to global warming, but a switch to dry powder inhalers is not so simple

An article in The Conversation calling on environmentally conscious patients to swap their puffers for dry powder inhalers is missing context, according to asthma experts.

In the article, which was later republished by the ABC, Western Australian GP Dr Brett Montgomery detailed the role that HFC metered dose inhalers (MDI) play in climate change, and advised patients with asthma to consider swapping to a dry powder inhaler.

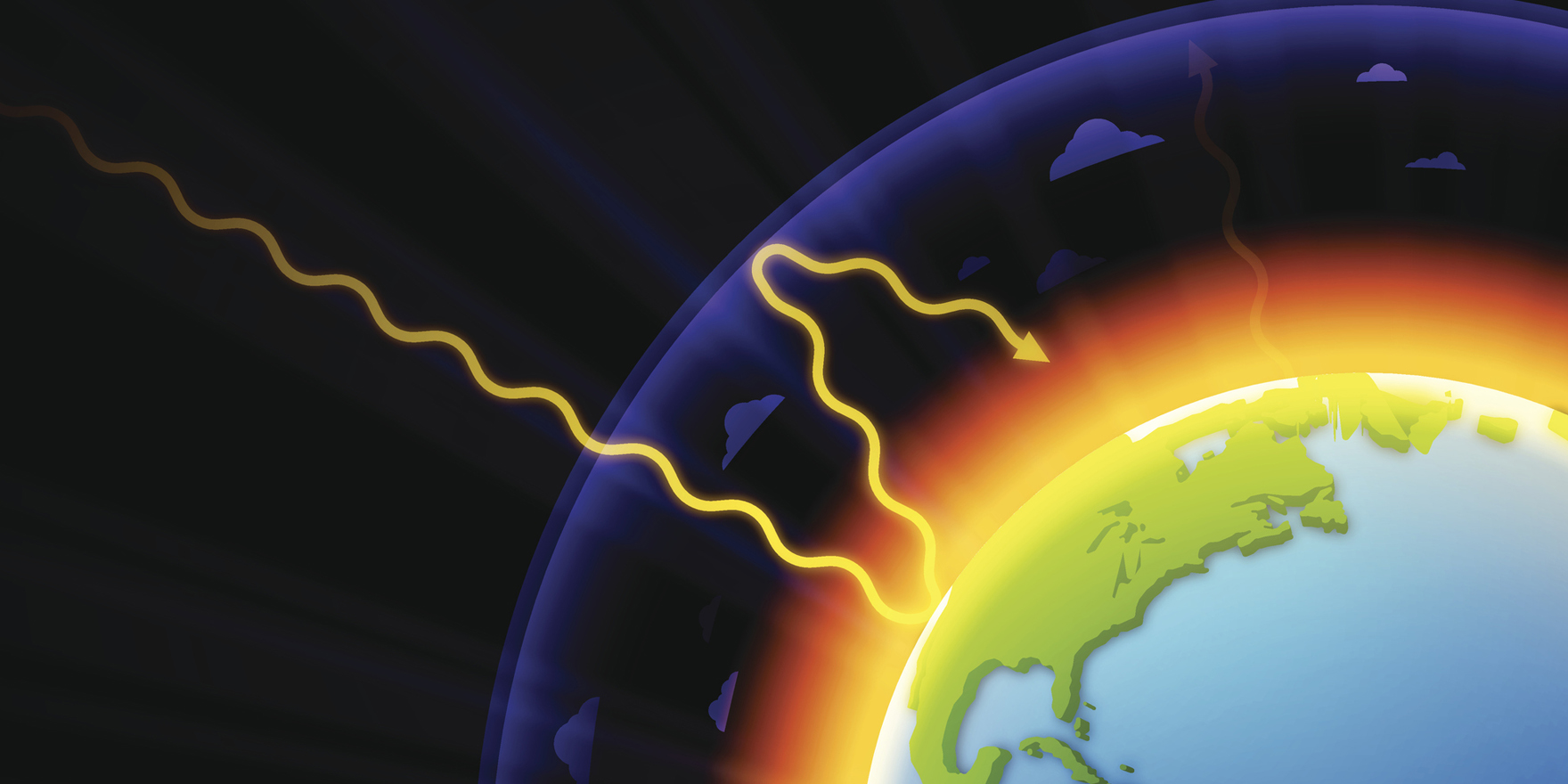

MDIs containing hydrofluorocarbons which contribute to global warming. In 2016, a global agreement was made to start phasing out HFCs in MDIs through the Kigali amendment to the Montreal Protocol.

Based on Dr Montgomery’s back-of-the-envelope calculations, a person using an HFC MDI monthly could easily release the annual equivalent of a quarter of a tonne of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

“That’s like burning 100 litres of petrol,” he said.

The solution was “easy”, Dr Montgomery said. Many people with asthma could shift from these MDIs to dry powder inhalers.

There were important exceptions, however: young children and people who struggled to inhale did better with HFC MDIs and spacers.

“If metered dose inhalers are a better choice for you, please don’t panic or quit your medicines,” Dr Montgomery said. “These gases probably won’t be the biggest contributor to your personal carbon footprint.”

The article’s emphasis on quitting MDIs rubbed some experts the wrong way.

For life-saving medications such as asthma puffers, patient safety and well-being should be at the centre, as we considered environmental concerns, Kristine Whorlow, past CEO of the National Asthma Council Australia, said.

“What we like to do is ensure a range of medicines, MDIs and DPIs, is available to suit patients’ needs,” she said.

The urge to action in The Conversation article was “not quite what my urge to action would be”, Professor Amanda Barnard, a GP who is Chair of the Guidelines Committee for the Australian Asthma Handbook, said.

The key message when treating asthma should be: choose a device type that was best suited to the individual, she said.

“For example, kids can’t use the dry powder device … and neither can some adults, particularly those with poor inspiratory flow.”

All dry powder inhaler medications are prescription-only in Australia, so patients who are relying on over-the-counter asthma medication such as salbutamol (Ventolin) need to consult with their GP to investigate a suitable, HFC-free alternative.

Patients really should be doing this anyway, as asthma could be better managed with GP oversight, Professor Barnard said.

Globally, HFC MDIs account for about 60% of total inhaler use. “That’s unlikely to change in the next decade,” Ms Whorlow said.

While use of these inhalers was decreasing in Europe and America, use was increasing in countries such as India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Russia, China, and Cuba.

“That is largely due to affordability,” Ms Whorlow said. The most commonly used asthma medication worldwide is salbutamol MDI.

The cheaper price is particularly relevant to developing countries where incomes are lower.

“The use of HFC MDIs will probably resolve over time to an extent,” she said.

“Dry powder inhalers will come off patent in about 2025, so they will be cheaper, but we are not there yet. Also, research is under way on alternative propellants for MDIs.”