While not yet commonplace, the role of private patient advocate is an emerging one. But do we really need them?

As health systems and treatment options grow ever more complex, a new kind of support role is becoming increasingly popular in the United States, UK and Europe – the private patient advocate.

Overseas, private patient advocates have been a common part of patient-centred care since the mid-2000s. With just a handful of private advocates operating in Australia to date, their introduction raises many questions, and it remains to be seen how this emerging industry will streamline our patients’ care.

For example, can Australian health professionals and patient advocates work comfortably together? Are private patient advocates necessary to bridge gaps in our own health system? To answer these questions, we need to look at what private patient advocates do, and where they “fit” in an already crowded, multidisciplinary health market.

WHAT DO THEY DO?

Private patient advocates help patients coordinate, translate and communicate the intricacies of diagnoses, treatments, support services and other aspects of healthcare.

Professional experience in the health industry – nursing especially – is common among private patient advocates. Others come from a legal background, or have experience as a long-term patient or carer.

Services provided by private patient advocates are many and various.

Examples include accompanying patients to appointments, taking notes, explaining medical jargon, arranging second opinions or specialist appointments, co-ordinating support services, managing medications and mediating disputes. Private patient advocates do not make any health decisions or legal decisions on the patient’s behalf, but can equip patients with the knowledge they need to inform those decisions.

These advocates are employed directly by a patient or a patient’s family, independent of a hospital, GP practice or any other healthcare organisation. Fees can vary depending on the kinds of services provided, the level of involvement in a case and the amount of travelling required. Clients can expect to pay between $100 and $150 per hour for a private patient advocate, which is not usually covered by health insurance.

Many roles within public health system combine to perform similar functions to those provided by a private patient advocate. Publicly funded consumer advocates, social workers, nurses, interpreters, discharge planners and other non-medical staff are available to most hospital patients. Though they have many names, collectively these roles can often provide all the advocacy services a patient needs.

But there is also recognition in some quarters that it is possible for patients to get “lost in the system”.

Last month, for example, the Minister for Aged Care, Ken Wyatt, released a draft of a National Aged Care Advocacy Framework, designed to “better empower people to exercise choice and control within the aged care system”.

In days gone by, there was a role of case management by a doctor within the hospitals, and that really no longer exists.

WHY GO PRIVATE?

Anyone who’s had a relatively smooth sail through the health system might wonder why someone would fork out hundreds of non-refundable dollars for services that can be provided collectively by a good GP, a hospital-support team and a committed family member.

But what if the patient is unaware of the hospital services available to them? What if they don’t have a good relationship with a holistic GP? Or the family is busy, disinterested or absent? What if the GP or specialists or hospital team is rushed or sloppy? Or communication is poor?

In the past, the system has been easier to navigate, and relatives were more likely to be available to be effective supporters or carers.

“There’s a big change in the social structure these days,” says Dorothy Kamaker of Patient Advocates Australia.

“The children of these people are often in their 40s, they’re at the peak of their careers, or at least they’re working as hard as they ever will, or they’ve got their own children.

“They’re called the sandwich generation – where they’re bringing up their own children but they’re supporting their parents.”

Other clients prefer to rely on a private advocate’s emotional detachment to help them deal with a distressing diagnosis.

A common selling point for private patient advocates is their independence. The fact that they are not beholden to any particular hospital, practitioner or bottom line, gives them a marketable ability to consider options for their clients that might not be offered by someone employed to represent an organisation.

“Patient advocates in hospitals do a lot of education with patients and that’s all fine,” Ms Kamaker says.

“That’s absolutely wonderful and they do a lot of referring around the hospitals, supporting them, referring them to other facilities in the hospital, and I don’t disagree with that.

“But I do think that what an employed patient advocate within an institution can never be is independent and look at the problem from everybody’s side.”

ARE THERE SHORTCOMINGS?

Imagine a world in which you could spend as long as you’d like with each patient. A world in which communication flows clearly and unfettered between patients, GPs, specialists, allied health professionals and hospitals. Where funding, forms and facilities are simple and freely available.

That’s a world that needs no private patient advocates, and right now, that is a world that doesn’t exist.

There’s no question that our health system is stretched; that population growth, time pressures and funding squabbles put pressure on doctors, nurses, allied health professionals and support staff to achieve more with less. Any canny businessperson would have no trouble finding gaps to fill, and private patient advocates clearly benefit when patients and their families struggle.

But is that all they’re doing? Are they exploiting cracks in the system for personal gain? Or are they a valuable extension of a system that has evolved beyond the comfortable grasp of the layperson?

Unsurprisingly, Ms Kamaker says her role is vital. “There wouldn’t be a need for us if the system got it right.” she explains.

“In days gone by, there was a role of case management by a doctor within the hospitals, and that really no longer exists. A lot of hospitals used to have patient advocate roles, and by and large that has disappeared, and now people have patient representatives or something that is really devolved into a troubleshooting role.”

Ms Kamaker emphasises that the expectations placed on patients to help manage their own care are currently greater than many people are ready to take on.

“In the last five or six years the health-delivery model has changed. It’s written into the Charter of Healthcare Rights that patients have rights and responsibilities. And those responsibilities are something that providers now rely on,” she says.

“I think there is a need for patients these days to be as smart as the people who are delivering the service, and that’s why people realise they need someone on their side and by their side all the time.”

Dr Bastian Seidel, President of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, agrees that there are shortcomings in the provision of health services in some sectors.

“I’m hearing from some patients that they are feeling pressured and pushed. When they go and see a GP they only spend a few minutes.

“When they go to a hospital they see a different doctor all the time and they’re in and out within two minutes as well. So it’s very confusing and they really don’t know whether they do receive the best care that they deserve,” he says.

On the question of whether private patient advocates are a suitable long-term solution, Dr Seidel is less certain.

“My feeling is, certainly in Australia, I can’t see it to be a long-term thing. It’s certainly a niche service that may be suitable for some patients. Absolutely. I cannot believe it’s going to be the norm anytime soon.

“That’s actually not what patients want. Patients don’t want more people involved. Patients want more control over the decisions they make, and they want more choice and they want more information. They certainly don’t want to outsource anything there.

“I think that would be a short-sighted approach. That doesn’t help us to raise levels of health literacy or to raise empowerment for our patients.”

Indeed, many of the opportunities for private patient advocates stem from the gap between what patients understand about their diagnoses, treatment and the workings of the health system, and what they need to know in order to manage it all themselves.

Health literacy is the currency of the private patient advocate.

MANAGING EXPECTATIONS

While barriers to seamless healthcare certainly exist, some issues crop up because of the disparity between what patients expect from the health system and what it can realistically provide.

Natalie* works as a consumer advocate in a public hospital in Victoria. She sees patient expectations as a fundamental factor of the healthcare equation.

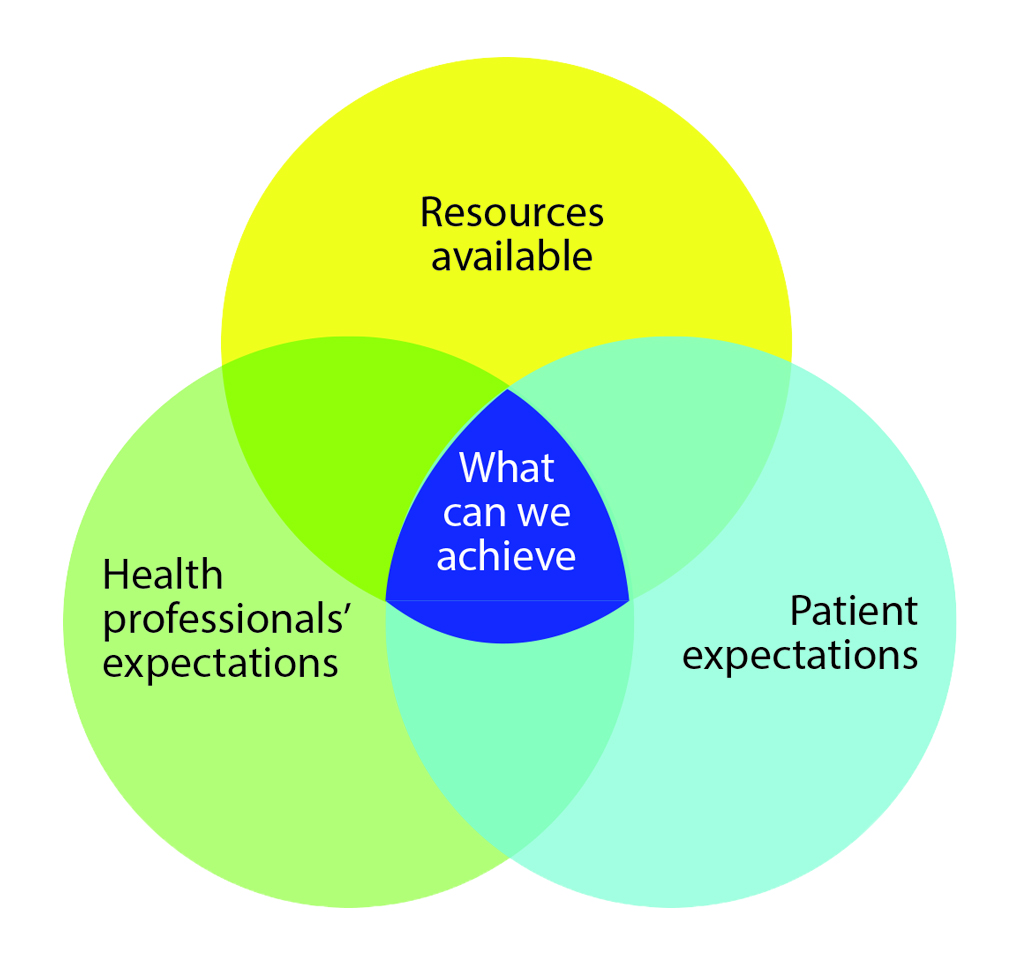

“I’ve got this really good Venn diagram. (See above)

One bubble is the resources available in the system, another bubble is the expectations of the health professionals, and the last is the expectations of the patients. And right in the convergence, that middle is what we can achieve. But you really need to factor in all those three circles.”

Equilibrium in such a structure is often difficult to obtain. Most practitioners have encountered patients or family members who have pushed for a particular course of action that wasn’t necessarily warranted by the patient’s condition; or who have complained about the way their case was handled when all correct procedures were followed.

Many of these cases can be resolved once the patient understands where their desires are at odds with what’s feasible – in other words, they want what’s outside the convergence of Natalie’s Venn diagram. However, a small number of patients persist with their objectives beyond what might be considered reasonable, and could see a private patient advocate as a valuable champion for their cause.

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

A good advocate with health experience will be able to explain why a patient’s complaint or treatment expectations are unrealistic, and be considered a more neutral player by the patient than the people treating them or processing their complaint.

The patient may feel more at ease working towards an effective compromise with a private advocate than they do with people they consider biased or inflexible.

Is there any evidence that patient advocates are improving patient outcomes? I’m not aware of anything, and that probably should be the main driver.

CRUX OF THE ISSUE

There are several studies that suggest patient health outcomes are improved when a support person, patient navigator or case manager is involved.

For example, a 2008 review published in Cancer1 found that cancer patients improved their standard of treatment when using a patient navigator.

Its discussion states, “Overall, there was evidence of some degree of efficacy for patient navigation in increasing participation in cancer screening and adherence to diagnostic follow-up care after the detection of an abnormality.”

A 2016 review in BMJ Open2 concluded:

“Our review suggests that case management could reduce ED visits and hospitalisations as well as cost, but additional studies still need to clearly confirm its effectiveness.”

On the more specific topic of private patient advocates’ effect on health outcomes, documented evidence is scarce.

“Is there any evidence that patient advocates are improving patient outcomes? I’m not aware of anything and that probably should be the main driver – to make sure we are improving patient outcomes.

“Because otherwise, just to pay somebody, why are we doing it?” says Dr Seidel.

Patient advocate Ms Kamaker adds:

“In Sydney and in Australia, in private practice, there are probably only three or four independent patient advocates practising at the moment … there may be half a dozen or so. So there is no critical mass there to do any kind of research.”

CAVEAT EMPTOR

In the fledgling business of private patient advocacy in Australia, there is currently no quality control or standard of qualification. Though many private advocates have a solid background in nursing or law, there is no restriction on who can become an advocate.

The field is equally open to competence and cowboys, and the onus is on the client to ensure the person they hire is suited to

the job.

Patient advocate Natalie maintains her nursing registration even though she works in a non-nursing role.

She sees the lack of regulation in the private advocate space as problematic, as they are dealing with vulnerable people who may not recognise the distinction between registered and unregistered professionals.

“There’s value in having some clinical credibility,” she says.

“I think it’s very similar to life coaches and psychotherapists. Anyone can call themselves a psychotherapist. You don’t have to be registered with AHPRA.”

SUPPLY AND DEMAND

There are some convincing arguments for using a caring and qualified private patient advocate. But in the present health environment, they are only available to those patients who can afford to pay out of their own pocket.

Arguably, the patients who stand to benefit most from the services of private patient advocates are those who can least afford to use them.

These are the patients who need help not only with health literacy, but also with interpreters, financial assistance and access to support services they may not know exist.

“There’s a real imbalance there,” says Natalie.

“I think the people who have the money to pay for a private advocate are already better placed than many of the people who need that service.”

THE FUTURE

Does the Australian health system have a permanent place for private patient advocates? The answer appears to be yes, but with conditions.

Though some health professionals may view private patient advocates as a temporary fix for cracks in a straining health system, it’s plausible they could evolve into a more permanent, complementary fixture.

For that to happen, more work needs to be done to regulate the standard of private patient advocacy, and to allow affordable access to patients who are currently priced out of the independent advocacy market.

*Natalie is a pseudonym for a consumer advocate working in a Victorian hospital.

References:

1. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cncr.23815/full

2. http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/9/e012353.full