GPs have a critical role to play in educating families about the parechovirus epidemic

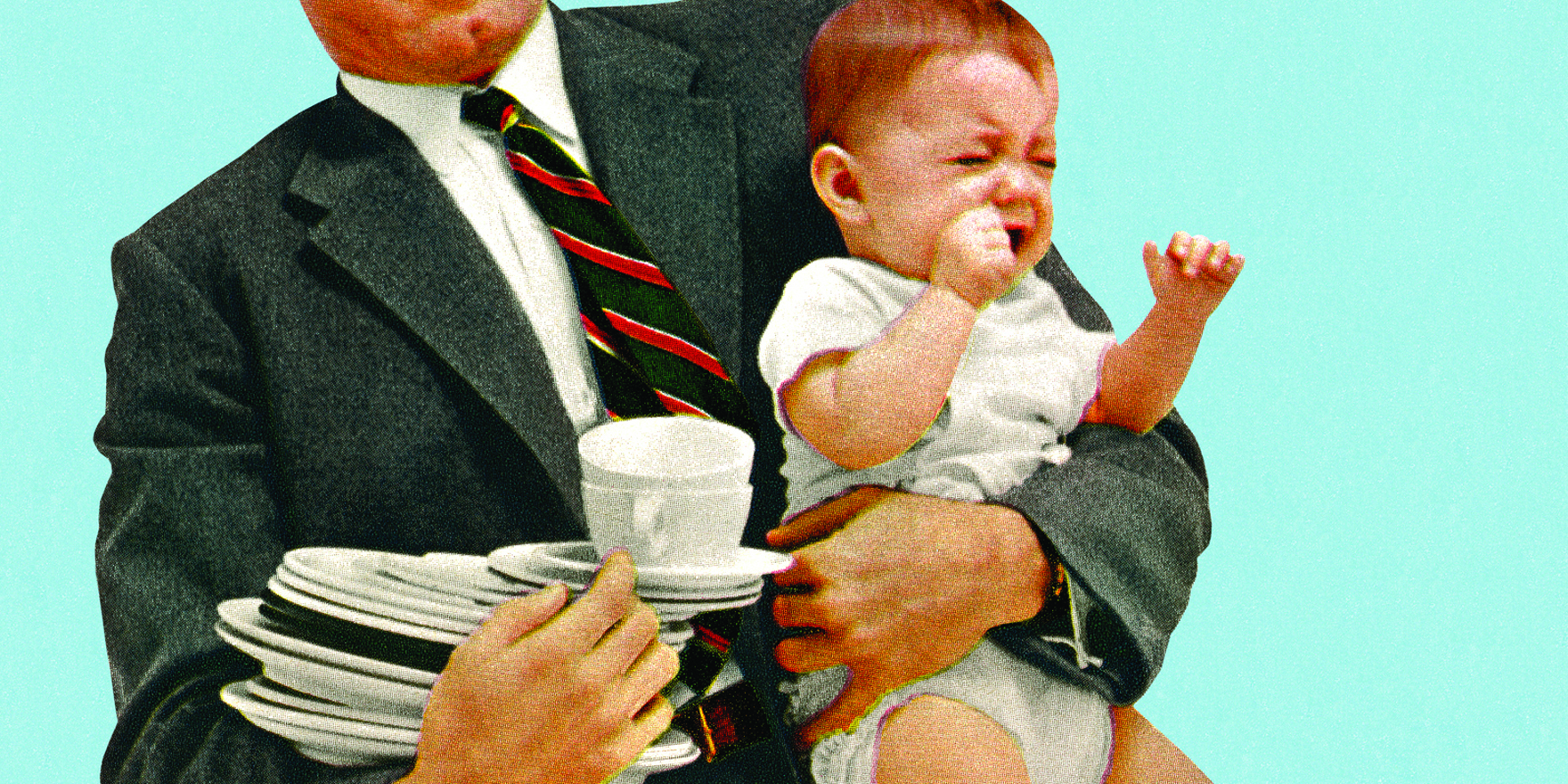

A red, hot, angry baby could be a sign the child has parechovirus, an infectious disease pediatrician has warned.

While a parent with the virus many only have a few sniffles or an upset stomach, the virus can cause severe sepsis-like symptoms in a young infant, Dr Philip Britton, the lead author of a recent MJA article on the topic, said.

“Some of these babies can present as if they’ve got a surgical abdomen, so a swollen belly, very irritable from what is presumed to be pain,” he said.

“That’s another clue in a very young baby that this could be parechovirus.

“Some of them will have complications of seizures, or weakness, floppiness.

“Occasionally, babies will have occasions of stopping breathing or apnoea.”

Three types of parechovirus commonly infect humans, genotypes 1, 3 and 6.

In a child under three months of age, parechovirus type 3 is the most severe, with around 10% of hospitalised infants having sepsis and meningoencephalitis.

Infants infected with type 3 usually present with symptoms of fever, rash and irritability.

If a parechovirus infection is suspected, the diagnosis can be confirmed by taking a stool sample and running the real-time TaqMan PCR test.

Basic infection control practices in the home, such as hand washing, and keeping sick people away from very young infants, were really the only way to prevent the spread of the disease, Dr Britton said.

Human parechovirus, a virus in the same genus as polio, has caused biannual epidemics among infants since the first cases started appearing across Australia in 2013.

Case numbers are on the rise and, last year, more than 200 young infants were hospitalised with the disease, leading to a public health warning being issued.

The virus is spread through saliva, nasal secretions and faeces.

GPs needed to be aware of parechovirus so that they could give advice around prevention, Dr Britton said.

“The majority of adults that get infected with parechovirus … have a mild gastroenteritis or a mild respiratory infection,” he said.

“But babies who acquire the disease are at risk of severe disease and adverse outcomes.

“A ‘cold’ in an adult where there is a young baby around, particularly in the first three months of life, is something that needs to be watched closely.”

The infection also has potential long-term consequences for neurodevelopment and a follow-up with a paediatrician was recommended, preferably until the child reaches school age and even after.

There is no specific antiviral therapy to treat patients with a parechovirus infection, and no broadly protective vaccine.

Infected babies are monitored closely in hospital, and given antibiotics for sepsis or meningoencephalitis, unless a bacterial infection is ruled out.

MJA 2018, 30 April