Medical issues arising from pregnancy can be distressing and require sensitivity, compassion and privacy

FIRST TRIMESTER BLEEDING AND ECTOPIC PREGNANCY

As many as one-in-four women experience vaginal bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy.1 The care for each patient should be individualised according to the pregnancy history to this point (including any investigations already performed) and whether she is haemodynamically stable. The pregnancy should always be confirmed objectively with a urine pregnancy test or a serum beta-hCG.

In the majority of cases, the bleeding is light and the patient can be managed in an out-patient setting by a GP, obstetrician or in an Early Pregnancy Assessment Service (EPAS). Women with heavy bleeding, severe pain, dizziness/collapse or other signs of haemodynamic instability need urgent assessment in the local emergency department.

Principles for resuscitation of a collapsed pregnant woman are beyond the scope of this article. It is worth remembering, however, that fit young women are able to compensate for blood loss very well; with tachycardic bleeding women, clinicians should not be falsely reassured by an apparently normal blood pressure, which may crash suddenly and rapidly.

Is the pregnancy intrauterine?

This is always the first question to consider for a woman with early pregnancy bleeding. Ectopic pregnancy is a potential surgical emergency. If an ultrasound has not already been performed, a scan to determine pregnancy location should be arranged without delay.

Is the pregnancy viable?

Most pregnancies (99%) are intrauterine. Following bleeding, the question then becomes whether the pregnancy is viable or not (i.e. is there a fetal heartbeat present). Ultrasound is the most important modality and, in many cases, a trans-vaginal scan (TVUS) will be required.

Strict criteria exist for diagnosing a miscarriage by ultrasound and the diagnosis should be only be made by credentialled sonographers and fetal medicine specialists.

In very early pregnancy (less than seven weeks), no pregnancy may be identified either inside or outside the uterus on ultrasound. This is termed a pregnancy of unknown location and a follow up scan at an appropriate interval (one to two weeks) is mandatory. The routine use of quantitative serum beta-hCG to assess viability in a known intrauterine pregnancy is not recommended.

MISCARRIAGE

Miscarriage – the loss of a pregnancy before 20 weeks – complicates approximately one-in-six pregnancies, with most miscarriages occurring before 10 weeks. Pejorative terms such as “spontaneous abortion” and “failed pregnancy” should be avoided.

Miscarriages usually present with some combination of abdominal pain/cramping and vaginal bleeding, but a miscarriage may also be “missed”. Missed miscarriages are typically diagnosed unexpectedly on a routine ultrasound. The patient may still have pregnancy symptoms and only minimal vaginal discharge, so she is especially upset to find that the pregnancy stopped developing several weeks earlier.

For women found to have a viable pregnancy after vaginal bleeding, the term used is “threatened miscarriage”. This is a non-specific term and underscores the fact that we cannot usually identify the source of the bleeding.

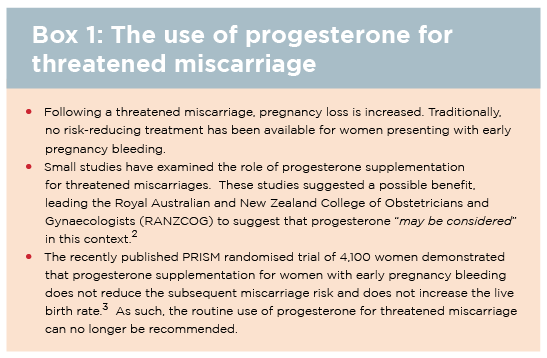

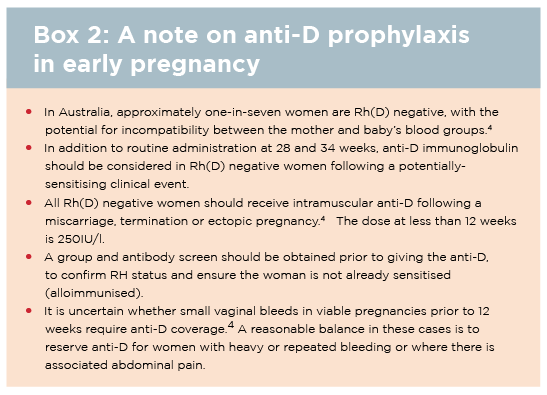

There is no proven treatment for reducing the risk in women presenting with threatened miscarriage (See box 1). If the pregnancy is non-viable on ultrasound, then the miscarriage should be classified as either complete or incomplete. This is a distressing time for most couples and requires sensitivity, compassion and privacy. Anti-D prophylaxis may be required for Rh(D) negative women (See box 2).

Management options for miscarriage

Expectant management: Women elect for a “wait and see” approach, to let their body miscarry spontaneously. This is most appropriate in cases where bleeding has already started and the miscarriage is incomplete.

For missed miscarriages, where the gestational sac is intact, the failure rate for expectant management approaches 50%.

Medical management: The miscarriage can be completed using medication. Misoprostol is given to stimulate contractions. The success rate is higher if 200mg mifepristone (RU-486) is given 24 to 48 hours prior to misprostol, although prescribing and dispensing mifepristone is strictly regulated in Australia (www.ms2step.com.au).

Medical management may not be appropriate at later gestations (greater than nine weeks) as the bleeding is often heavier and the patient may find the experience psychologically traumatic.

Surgical management: Uterine curettage is mandatory for haemodynamically-compromised or septic women and where there is a suspicion of a molar pregnancy. Surgical management is also the treatment of choice in cases not suitable for, or who decline, or who have already failed expectant/medical options.

Surgical curettage is most commonly performed under anaesthesia in an operating theatre. In experienced hands, serious complications – such as uterine perforation, haemorrhage and cervical lacerations – are uncommon.

ECTOPIC PREGNANCY

Pregnancies implanting outside the uterine cavity (ectopic) may rupture, with the potential for life-threatening intra-abdominal haemorrhage. Approximately 1% of all pregnancies are ectopic.5

Women with a previous ectopic (15% recurrence risk), IVF pregnancies and those with pelvic inflammatory disease are at high risk.

All women presenting with vaginal bleeding and/or pain in early pregnancy should be considered to have an ectopic pregnancy until proven otherwise. TVUS is the investigation of choice.

Most ectopics (98%) are in the fallopian tube and an adnexal mass may be identified directly on scan.

No evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy with a serum beta-hCG greater than 1500IU/L is also highly suspicious. For stable women with a pregnancy of unknown location, serial quantitative beta-hCG levels are useful (the typical pattern with ectopic pregnancy is a slowly rising hCG). However, there is wide variation in the trajectory of hCG in normal pregnancies and serial hCG levels should only be interpreted by an experienced practitioner.

Women with suspected ectopic pregnancy should be referred urgently to the local EPAS for assessment by a senior obstetrician/gynaecologist. Laparoscopic salpingectomy (removal of the ectopic and the affected tube) is the treatment of choice in most cases. Carefully selected early ectopics (beta-hCG less than or equal to 3,000-5,000IU/L) without evidence of rupture can be managed medically with systemic methotrexate.5

NON-OBSTETRIC CAUSES OF VAGINAL BLEEDING IN EARLY PREGNANCY

For women with post-coital vaginal bleeding in pregnancy, the cause is often a cervical ectropion – which is common in pregnancy and usually identifiable on speculum examination. In such cases, the woman can be reassured and intercourse does not need to be avoided.

A pap smear history should be obtained and sometimes the speculum examination may reveal a cervical polyp or, very rarely, a suspicious mass. Women with unusual cervical lesions in pregnancy should be referred for an urgent colposcopy by an experienced gynaecologist.

Lastly, irregular vaginal bleeding may occasionally be the presenting symptom in a case of molar pregnancy or choriocarcinoma, particularly with very elevated serum beta-hCG levels, although these conditions are rare.

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS

Chlamydia and gonorrhoea

Chlamydia and gonorrhoea are commonly diagnosed infections in pregnancy. RANZCOG does not recommend universal screening for chlamydia in pregnancy but rather selective screening of those at increased risk.6 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women are at increased risk with a prevalence of one in six for chlamydia in pregnant women.7

Chlamydia is often asymptomatic or may present with dysuria, pelvic pain or abnormal vaginal discharge; it should always be considered in pregnant women with sterile pyuria. The treatment of choice in pregnancy is 1g oral azithromycin.

Gonorrhoea typically presents with symptoms of cervicitis – discharge or dyspareunia – or anorectal symptoms. Like chlamydia, gonorrhoea is frequently asymptomatic. The recommended treatment in pregnancy is 500mg IM ceftriaxone with 1g azithromycin orally, although antimicrobial resistance is emerging in remote Australian locations.8

Both chlamydia and gonorrhoea are best diagnosed on an endocervical swab (which is safe in pregnancy) or a self-collected vaginal swab or, if swabs are not possible, a first pass urine. Following treatment for these infections in pregnancy, a test of cure is mandatory at four weeks.8

Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

HSV is very common in pregnancy and more than 50% of genital herpes is due to HSV-1.8 Genital swab and HSV serology are recommended if this is the first episode. Oral acyclovir is the treatment of choice and is safe in pregnancy (400mg TDS for five days).

Specialist advice is recommended for HSV diagnosed close to term or in labour, as there is a risk of neonatal transmission.

Daily suppressive antiviral therapy commencing at 36 weeks is only indicated in women with frequent symptomatic recurrences.

PRE-ECLAMPSIA

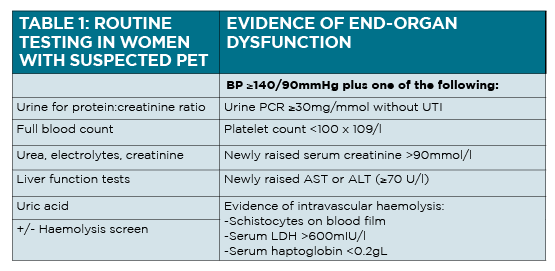

Pre-eclampsia is a common obstetric complication, affecting 3% of Australian pregnancies.9 It is a multi-system disorder defined as new-onset hypertension (BP ?140/90mmHg) occurring after 20 weeks gestation, with evidence of end-organ dysfunction (if there is new onset hypertension without end-organ dysfunction, this is called pregnancy-induced hypertension).10

Of women who develop pre-eclampsia in pregnancy, more than 80% will present after 34 weeks, which is why regular antenatal checks are warranted late in pregnancy. Pre-eclampsia is more common in first pregnancies, in twin/triplet pregnancies and in women with diabetes, renal disease or thrombophilia.

What “end-organ dysfunction” is required to make a diagnosis of pre-eclampsia?

New proteinuria: The best test is a spot urine protein-creatinine ratio (PCR); dipstick urinalysis is not sufficiently sensitive and 24-hour urine collections are too cumbersome for routine use.

In the absence of proteinuria, newly abnormal serum biochemistry makes the diagnosis. (See table 1 above) Although serum uric acid is often increased in pre-eclampsia, it is not sufficient for making a new diagnosis.

Typical symptoms suggestive of pre-eclampsia: Severe headache which is often frontal and not improved with paracetamol, visual disturbance, nausea and vomiting or epigastric/RUQ pain. Clinical signs include hyper-reflexia, clonus, epigastric/RUQ tenderness, pulmonary oedema, severe peripheral oedema

Management of pre-eclampsia

Although pre-eclampsia is not an obstetric emergency per se, some women – especially those with onset before 34 weeks – can develop fulminant hypertension rapidly. Therefore, all women with suspected pre-eclampsia should be referred to the local maternity service for prompt obstetric assessment.

The only cure for pre-eclampsia is delivery of the baby and placenta. For women with confirmed pre-eclampsia at or beyond 37 weeks, delivery is indicated, usually by induction of labour.

Women with pre-eclampsia who are preterm (less than 37 weeks) are usually managed expectantly with anti-hypertensive medication, regular blood testing and close fetal monitoring.

If the BP exceeds 160/110mmHg, urgent admission for anti-hypertensive treatment is mandatory.

The oral anti-hypertensive agents of choice for women with pre-eclampsia are labetalol (100mg-400mg tds or qid) and methyldopa (250mg-750mg BD or tds). Oral hydralazine 25-50mg tds may be added as a second line agent.

Oral nifedpine may be helpful for urgent control of severe hypertension and slow release nifedipine is used frequently in the postpartum period.10

ANTEPARTUM HAEMORRHAGE

Antepartum haemorrhage describes vaginal bleeding in a pregnancy beyond 20 weeks (prior to 20 weeks it is termed a threatened miscarriage).

Antepartum haemorrhage complicates 2-5% of all pregnancies and is a very common cause for presentation to hospital in later pregnancy. Although most instances of antepartum haemorrhage are associated with mild bleeding only, vaginal bleeding after 20 weeks should always be considered abnormal and investigated, with the exception of a slightly blood-stained “show” (passage of cervical mucus) in a term pregnancy.

PLACENTA PRAEVIA

For early pregnancy bleeding, the first question is always “where is the pregnancy?” (i.e. intrauterine or ectopic). For antepartum haemorrhage, the first question to consider is always “where is the placenta?”.

Vaginal examination must never be performed in a woman with antepartum haemorrhage until the location of the placenta is ascertained. The 18-20 week fetal anatomy ultrasound report should be reviewed if available. If not, a scan to assess the placental location is warranted.

Placenta praevia refers to a placenta which covers the internal cervical os. If the placental edge lies within 20mm of the os but does not cover the cervix, the term “low-lying placenta” is preferred.11

With true placenta praevia, the presenting part cannot engage, so abdominal examination may reveal a floating head, or breech or a transverse lie.

The rate of placenta praevia is approximately 0.5% in term pregnancies and is more common in smokers and in IVF pregnancies. Clinicians should be familiar with two related conditions:

Bleeding in a woman with an anterior placenta praevia and a history of a prior caesarean section should be a particular red flag. In this case, there is a risk of placenta accreta spectrum (morbidly adherent placenta), with the potential for non-separation of the placenta and massive obstetric haemorrhage at the time of delivery.11

Vasa praevia is a rare (one in 2,500 pregnancies) condition, defined as fetal vessels directly over the cervix, often seen in combination with a placenta praevia . If the membranes rupture, the fetal vessels may be disrupted which can lead to rapid fetal exsanguination and death.

Delivery in vasa praevia is always be caesarean section and usually preterm (35-36 weeks) to minimise the chance of spontaneous labour.

PLACENTAL ABRUPTION

An abruption refers to a retro-placental bleed in a normally-sited (not praevia) placenta.

The classic presentation of a placental abruption is an antepartum haemorrhage associated with abdominal pain/cramping and tenderness because the blood clot behind the placenta irritates the uterus.

In contrast, placenta praevia is typically associated with painless bleeding. Risk factors for placental abruption include hypertension, cigarette smoking and cocaine use, known thrombophilia and abruption in a previous pregnancy but in many cases there are no identifiable risk factors.

While placental abruption complicates 1% of pregnancies, most are small bleeds which resolve with conservative measures.

Women presenting with an antepartum haemorrhage after 23 weeks are almost always admitted to hospital for a period of close observation with IV access in place, as even a small bleed may herald a subsequent larger bleed.12

Rh(D) status should be checked as prophylactic anti-D may be indicated (See box 2 on page 26). Common practice is to patients admitted until they have been bleed-free for at least 24 hours.

Occasionally, if a woman presents with recurrent bleeding, a prolonged admission until delivery may be warranted although the psychological impact of prolonged admission on the patient should not be underestimated.

Less commonly, woman may present with signs of hypovolaemia and haemorrhage following a massive placental abruption. The blood flow to the uterus at term is 600mL/minute, so a massive abruption can rapidly lead to haemorrhagic shock.

Usually there will be heavy vaginal bleeding but some severe abruptions can be concealed (there is significant haemorrhage behind the placenta but no overt vaginal bleeding). In cases of concealed abruption the only clue may be severe abdominal pain or back pain and a tense abdomen.

The standard principles of maternal resuscitation should be followed and, if available, a massive transfusion protocol should be activated as large quantities of blood products may be needed rapidly.12

Massive abruptions can result in stillbirth or the need for urgent caesarean section. Even in cases of fetal death in utero, a laparotomy is often still needed to achieve haemostasis.

PRETERM LABOUR AND PRETERM BIRTH

In developed countries, including Australia, 5 to 10% of babies are born preterm. Although preterm birth refers to a baby born before 37 weeks, serious complications of prematurity usually only develop in babies born at less than 34 weeks (and, in particular, babies born at less than 30 weeks).

A minority of preterm births (25%) are high-risk pregnancies where a decision is made to deliver the baby early due to obstetric complications. However, in most cases, early delivery is due to unexpected spontaneous preterm labour.

Women with twin/triplet pregnancies, women who smoke and those with a history of a previous preterm birth are particularly high risk groups.

Preterm birth prevention

The best predictor of a woman’s individual risk of preterm birth is the length of her cervix in the second trimester. Most experts agree that all pregnant women should have their cervical length measured ultrasonographically at the time of the routine 18-20 week fetal morphology scan.

This “universal screening” approach means that women with no obvious risk factors on history are more likely to be identified. A “short cervix” is most widely defined as a cervix less than 25mm in a singleton pregnancy prior to 24 weeks.13 Women with a short cervix are at significantly increased risk (30%) of preterm birth.

There is now overwhelming scientific evidence that vaginal progesterone decreases the risk of preterm birth following identification of a short cervix on mid-trimester scan, both in women with and without a history of prior preterm birth.14

The most common dose is 200mg progesterone pessary inserted vaginally once daily (usually at bedtime) and continued until 34-36 weeks. Intramuscular progesterone is not available in Australia.

A vaginal swab and MSU should also be sent in women with a short cervix, so that any infective source can be treated promptly.

Cervical cerclages are now being inserted less and less frequently and are reserved for the most extreme cases.

For most women with a short cervix, progesterone is equally efficacious and avoids the operative risks of the cervical stitch.

Occasionally, a cerclage may be indicated for women with a history of multiple late miscarriages or preterm births, or in women whose cervix continues to shorten despite vaginal progesterone treatment but these decisions should be made by a maternal-fetal medicine specialist.

Preterm labour

Labour is defined as regular painful uterine contractions associated with cervical change. Often, at preterm gestations, women may present to hospital with mild uterine contractions (threatened preterm labour) and it may be some hours until cervical change becomes apparent. Cervical assessment with a vaginal examination or a TVUS is critical to identify those at highest risk.

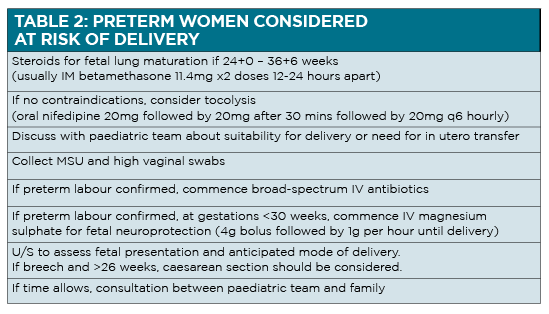

In addition, a swab for fetal fibronectin has a high negative predictive value for delivery within the next week. In many cases, the mild tightenings settle with rehydration and oral analgesia. Indeed, only 10% of women with threatened preterm labour will deliver on that admission. If there is a high chance of delivery, urgent treatment is warranted to improve the neonatal prognosis (See table 2 on page 27).

Steroids for fetal lung maturation were traditionally given to women at 24-34 weeks; recent data suggest a benefit up to 36 weeks.15

Dr Colin Walsh is obstetrician and maternal-fetal medicine specialist at North Shore Private Hospital, St. Leonards, Sydney, NSW

References:

1. www.health.vic.gov.au/edfactsheets/downloads/bleeding-in-early-pregnancy.pdf

2. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. C-Obs 29a. Progesterone support of the luteal phase and in the first trimester. 2018.

3. Coomarasamy A, Devall AJ, Cheed V et al A Randomized Trial of Progesterone in Women with Bleeding in Early Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380: 1815-1824.

4. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. C-Obs 6. Guidelines for the use of Rh(D) Immunoglobulin (Anti-D) in obstetrics in Australia. 2015.

5. Elson CJ, Salim R, Potdar N et al on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. BJOG 2016; 123: e15–e55.

6. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. C-Obs 3b. Routine antenatal assessment in the absence of pregnancy complications. 2016.

7. Graham S, Smith LW, Fairley CK, Hocking J. Prevalence of chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and trichomonas in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Health. 2016; 13: 99-113.

8. www.sti.guidelines.org.au

9. https://beta.health.gov.au/resources/pregnancy-care-guidelines/part-d-clinical-assessments/risk-of-pre-eclampsia

10. Lowe SA, Bowyer L, Lust K et al. Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand. Guidelines for the management of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. 2014.

11. Jauniaux ERM, Alfirevic Z, Bhide AG et al. Placenta Praevia and Placenta Accreta: Diagnosis and Management. Green-top Guideline No. 27a. BJOG 2018.

12. www.kemh.health.wa.gov.au/~/media/Files/Hospitals/WNHS/For%20health%20professionals/Clinical%20guidelines/OG/WNHS.OG.AntepartumHaemorrhage.pdf

13. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. C-obs 27. Measurement of cervical length for prediction of preterm birth. 2017.

14. Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R, Da Fonseca E et al. Vaginal progesterone is as effective as cervical cerclage to prevent preterm birth in women with a singleton gestation, previous spontaneous preterm birth, and a short cervix: updated indirect comparison meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018; 219: 10-25.

15. Gyamfi-Bannerman C, Thom EA, Blackwell SC et al. Antenatal Betamethasone for Women at Risk for Late Preterm Delivery. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374: 1311-20.