This summer’s bushfire smoke killed hundreds and caused thousands of additional hospitalisations

Air pollution from the devastating bushfires this summer was responsible for more than 400 deaths and several thousand extra hospitalisations for heart and lung problems, early research reveals.

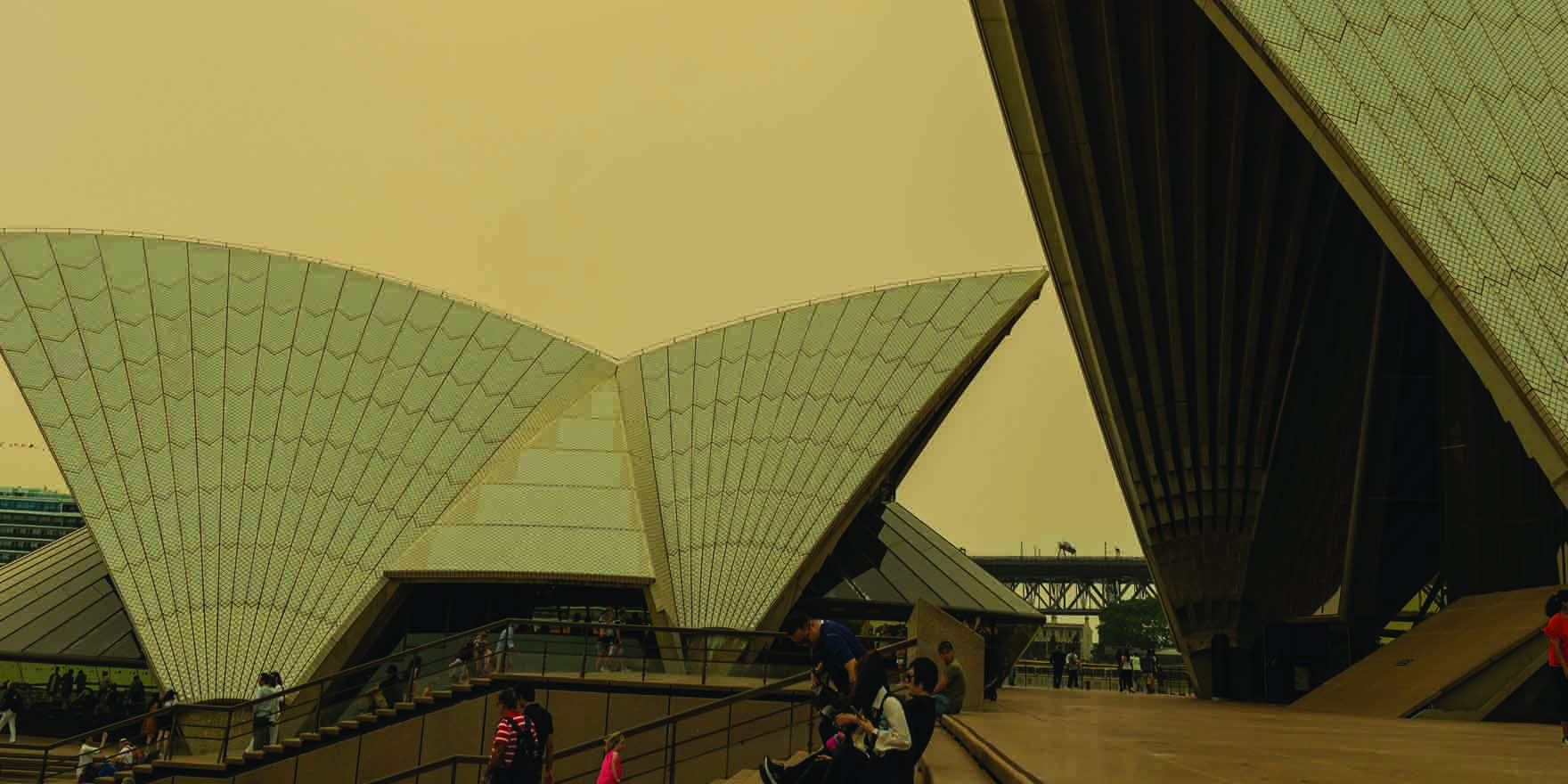

The unprecedented bushfire season razed almost 20 million hectares, killed possibly one billion animals and choked towns and cities in eerie smoke. Despite warnings from public health experts to stay inside as much as possible and be alert to exacerbations of chronic diseases, it appears that thousands of people were unable to protect themselves.

Research from Associate Professor Fay Johnston, at the University of Tasmania, and colleagues, shows that compared with normal years, the poorer air quality from the bushfires led to an additional 417 deaths, 1124 hospitalisations for cardiovascular issues, 2027 for respiratory problems and 1305 presentations to emergency departments for asthma in the eastern states.

More than half of the population was affected by the smoke, a separate study from the Australian National University suggests.

“So even though the effects can be subtle, if you are already at high risk of a heart attack or an asthma attack, then it’s really serious,” Professor Johnston, a public health physician and epidemiologist, said.

“When we are talking about exposing millions of people, and for a few months, not just day or a week, which is more common for fire smoke, the numbers add up, and add up dramatically.”

To understand the burden of the bushfire smoke on the health of Australians, Professor Johnston and her colleagues analysed the publicly available air quality monitoring data from NSW, Queensland, Victoria and the ACT in the last quarter of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020.

They looked at the number of days where people’s exposure to fine particulate matter was elevated above usual background concentrations measured in summer months over the past 20 years. They then modelled the effects of the increased smoke using population and health data to calculate excess numbers of deaths and hospital presentations attributable to the increased air pollution.

Researchers are interested in fine particulate matter, called PM2.5 because the diameter is 2.5 microns or less, because the tiny particles can get deep into our lungs and even blood streams. Exposure has been linked to death, lung and heart problems.

This study found that on 125 out of 133 days, at least one monitoring station saw concentrations of fine particulate matter exceed levels recorded on 95% of the other days in the historical data.

At its worst, the average concentration of fine particulate matter across all the regions that were studied reached 98.5 ?g/m3 on January 14, which was more than 14 times the usual background levels and some individual places experienced many days with concentrations far higher.

As well as preparing patients for the impact of fire smoke, Professor Johnston said health professionals had a role in advocating for the mitigation of climate change.

These death and hospitalisation rates are supported up by previous research on shorter term exposures of one or two days, Professor Brian Oliver, at the University of Technology Sydney, said.

Professor Oliver said he was surprised the number affected wasn’t higher, suggesting that the consistent public health messaging might have helped people protect themselves from the worst of it.

Nevertheless, these early figures on deaths were only the “tip of the iceberg”, he noted.

“We don’t yet know what it has done to children or middle-aged people, and what this kind of exposure means to their long-term health.”

Professor Johnston and her team are planning more extensive research into the effects of the bushfire smoke.

MJA; Doi: 10.5694/mja2.50545