Figuring out the links between Kawasaki’s disease and the virus that causes COVID-19 is ‘multiplying unknowns by unknowns’

Children have escaped the worst of the pandemic, but a hyperinflammatory syndrome is emerging that resembles Kawasaki’s disease and could be a rare complication of COVID-19.

There have been no cases in Australia yet of what has been dubbed paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS), but Chief Medical Officer Professor Brendan Murphy has sought advice.

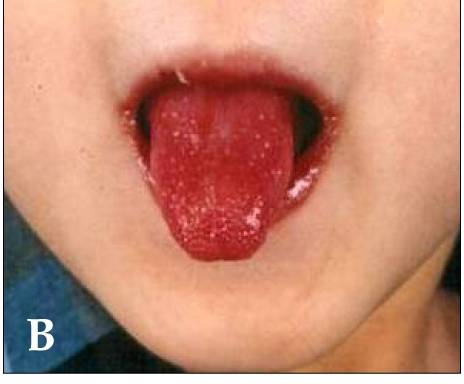

The first publication was a letter in the Lancet describing a cluster in London in April of eight children who presented at hospital with no respiratory symptoms but with prolonged fever, rash, conjunctivitis, abdominal pain and GI symptoms, swollen tongue papillae, peripheral oedema and pain in the extremities. They had inflammation in the coronary arteries and the heart muscle.

This same constellation of symptoms, together with swollen lymph nodes, constitutes Kawasaki’s disease, a rare multisystem vasculitis that affects mostly children under five, with a few hundred cases a year in Australia.

Its causes are still mysterious, but it requires a genetic predisposition and a trigger such as an infection. It’s more prevalent in Japan and Korea thanks to a genetic variant that is far more common in those populations. Untreated it can cause coronary aneurysm.

There is no test, and diagnosis is based on having four or five of these non-specific symptoms, a cardinal one being coronary artery abnormalities, says Dr Angus Stock, a research scientist developing immunotherapies for Kawasaki’s at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

The children in London all went into warm vasoplegic shock – which is one outcome of typical Kawasaki’s disease, affecting about 5% of cases – and were given a range of treatments including IV immunoglobulin, the standard treatment for Kawasaki’s disease.

Reports of similar presentations followed from New York, then around the US, and most recently from France and northern Italy – but not, interestingly, from Japan or South Korea.

Dr Stock told TMR the symptoms fitted quite well with Kawasaki’s but there were also some inconsistencies, such as the older age range.

“There’s a lot of unknowns with Kawasaki’s disease, and now you’re multiplying those unknowns by another unknown in COVID-19,” he said.

Most cases have been PCR-negative for the virus, but serology-positive, suggesting a past infection, Dr Stock said.

The fact it was appearing in teens could be due to the novelty of SARS-CoV-2 – for the more common infectious triggers, older children have had the chance to develop immunity.

But Dr Stock said it was interesting that this presentation had not been reported in Japan or South Korea.

“Either it’s not Kawasaki’s disease or the genetic predispositions are different to what we would normally associate with Kawasaki’s disease,” he said.

There had been speculation that the virus had mutated to become more inflammatory after it left Asia for Europe, Dr Stock said.

Or obesity could be the key. All but one of the children described in the Lancet were “significantly above the 75th percentile for weight”.

Obesity is a major risk factor for poor COVID-19 outcomes in adults. Recent papers have found high proportions of paediatric ICU patients had comorbidities including obesity and an inverse relationship between age and BMI in ICU patients.

“There’s a direct link between obesity and hyperinflammation,” Dr Stock said. “So certainly it is possible that obesity exaggerates the inflammatory response to this virus.”

Ultimately, whether this was true Kawasaki’s was just “a nomenclature issue”, and what was critical to ascertain was whether the therapies that work in that disease would also work in this setting – namely IVIG, anti-TNF and anti-IL-1beta drugs.

In contrast, the IL-6 blocker tocilizumab – which has shown some promise in adults with hyperinflammatory reaction to SARS-CoV-2 – had a negative effect in children with Kawasaki’s disease so should be avoided.