Lifestyle modification is the first-line of treatment for polycystic ovary syndrome and can significantly improve symptoms and risks, writes Dr Kate Marsh

Women with PCOS have an increased risk of impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk factors, as a result of underlying insulin resistance.1

They are also more likely to be overweight or obese, and carrying excess weight worsens metabolic and reproductive risk factors.2,3

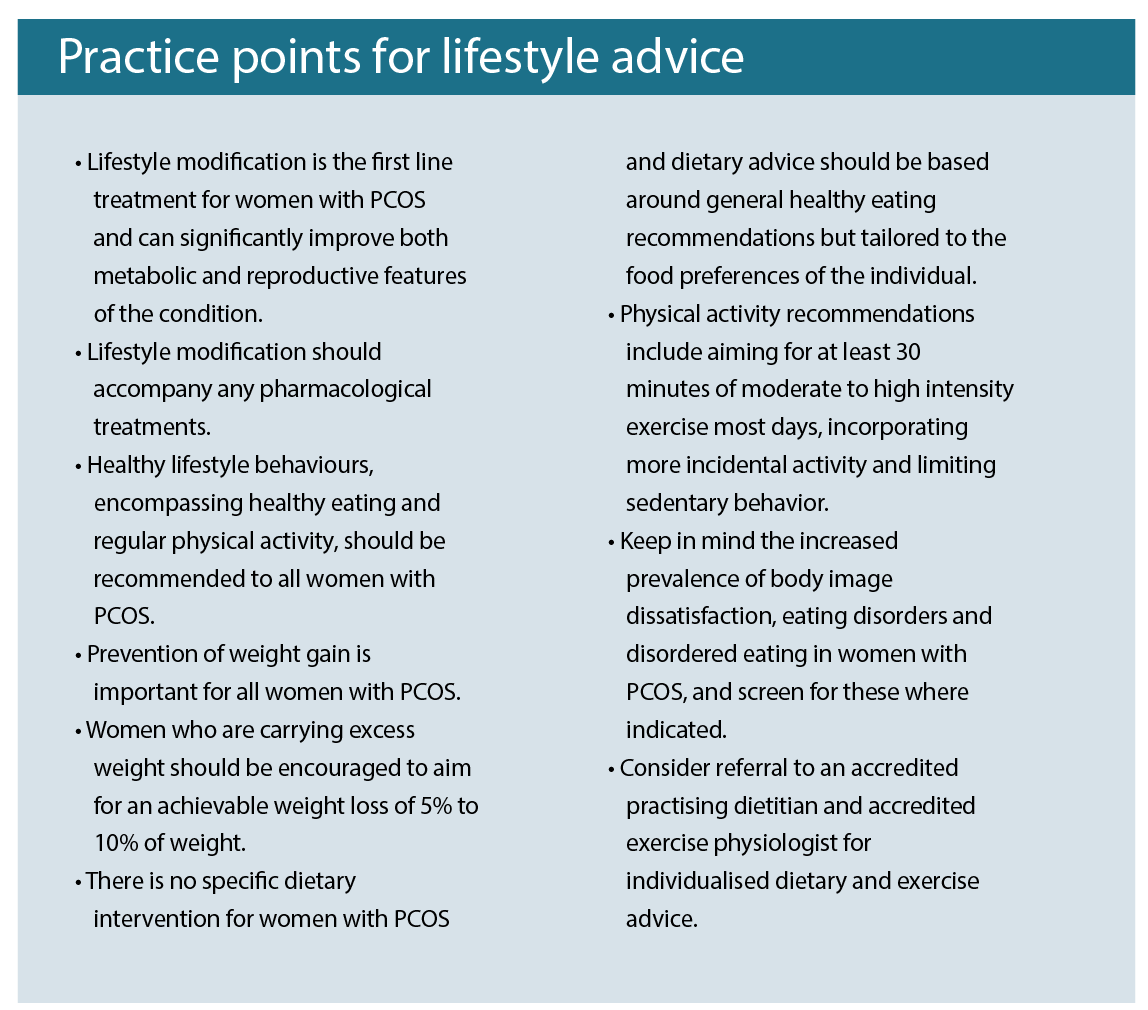

Lifestyle modification, including diet, exercise and weight management, is therefore recommended as the first line of treatment and has been shown to improve body composition, hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance.4-7

While some women may also require pharmacological treatments, these are recommended to be prescribed alongside lifestyle changes.8

Despite the importance of lifestyle modification, studies show that the majority of women with PCOS feel they don’t receive the information and support they need to help in managing their condition.9-11

While women report getting most of their information from specialists and the internet, the quality of this information is variable and a recent study found that few women were satisfied with information about PCOS given at diagnosis, including information on lifestyle management.12

Importantly, one study found that women who perceived receiving inadequate information about PCOS had poorer quality-of-life measures.13

This article will summarise the current nutrition and lifestyle recommendations for women with PCOS, to help health professionals provide evidence-based information, guidance and support to these women.

NUTRITION

Despite the important role of diet, long-term, well controlled studies investigating different dietary approaches in women with PCOS are lacking.8 While dietary interventions resulting in weight loss have shown benefits, there is currently insufficient evidence to support one specific type of diet over another. 8 For this reason, general healthy eating recommendations should be encouraged, focused on weight loss in those who are overweight and prevention of weight gain in those who are of a healthy weight.

Women with PCOS are more likely to be overweight or obese, particularly with central adiposity, and there is evidence that rates of weight gain are greater than in the general population.2,14 Excess weight worsens reproductive, metabolic and psychological features of the condition.3 It is also a significant concern for women themselves in terms of self esteem.

While women with PCOS often report difficulties with losing weight, a recent systematic review of weight loss interventions found no differences in weight loss between those with or without PCOS.15

This is an important message, as a recent US study found that women with PCOS had a greater perceived susceptibility for disease and weight gain and poorer perceived control over these health outcomes.16

They were also less likely to agree that a healthy diet or physical activity could reduce risk of weight gain compared to women without the condition.16

Helping women understand the benefits of lifestyle modification, even with quite modest weight loss (5-10% of weight), may increase their self-efficacy and motivation to make lifestyle changes.

The following list includes the nutrition and weight management recommendations from the 2018 international evidence-based guidelines for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome:7

• General healthy eating principles should be followed for all women with PCOS across the life course, as per general population recommendations.

• There is no or limited evidence that any specific energy equivalent diet type is better than another for women with PCOS.

• In women who are overweight or obese, a variety of balanced approaches could be recommended to reduce dietary energy intake, as per general population recommendations.

• To achieve weight loss in those with excess weight, an energy deficit of 30%, or 500-750kcal/day, could be prescribed, also considering individual energy requirements, body weight and physical activity levels.

• Dietary changes should be tailored to food preferences, allowing for a flexible and individual approach to reducing energy intake and avoiding unduly restrictive and nutritionally unbalanced diets.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Alongside diet, physical activity plays an important role in the management of PCOS. Regular exercise has been found to improve anthropometric and metabolic outcomes in women with PCOS although the impact on reproductive outcomes is unclear.17 Similar to diet, there is limited evidence for the benefits of specific types of exercise for PCOS, and recommendations are the same as those for the general population.7

The following list includes the physical activity recommendations from the same 2018 internatinal guidelines:

• For general health and prevention of weight gain in adults, aim for at least 150 minutes per week of moderate intensity exercise or 75 minutes per week of vigorous intensity exercise or an equivalent combination of both, including muscle strengthening exercises on two non-consecutive days per week.

• For general health and prevention of weight gain in adolescents, aim for at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity per day, including muscle strengthening exercises at least three times per week.

• For modest weight loss and prevention of weight regain, aim for at least 250 minutes per week of moderate intensity exercise or 150 minutes per week of vigorous intensity exercise or an equivalent combination of both, including muscle strengthening exercises on two non-consecutive days per week.

• Aim for at least 10000 steps per day, including activities of daily living and 30 minutes (~3000 steps) of structured physical activity, with a minimum of 10 minutes (~1000 steps) at a time.

• Minimise sedentary, screen and sitting time.

BODY IMAGE AND DISTORTED EATING

Several studies have reported a higher prevalence of body image concerns and disordered eating in women with PCOS and a recent meta-analysis of seven studies found these women had more than three times the odds of having abnormal eating disorder scores or an eating disorder diagnosis.18

The reasons for a higher frequency of disordered eating is unclear but is likely a result of a higher prevalence of risk factors including being overweight/obese, anxiety, depression and body image dissatisfaction, along with concerns about weight. In a survey of 1385 women with PCOS from 32 countries, difficulty losing weight was the most commonly cited concern.12

These findings highlight the importance of screening women with PCOS for disordered eating before recommending weight management interventions. The international guidelines emphasise the importance of health professionals being aware of the increased prevalence of body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating in these women and recommend screening for these conditions where suspected.7

Identification and management is important for improving the psychological functioning and overall quality of life, and reducing associated health risks.7 Further assessment, referral and treatment, including psychological therapy, should be offered where indicated.7 The guidelines provide initial questions to screen for body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating at the time of diagnosis of PCOS.8

BEING PREPARED

Women with PCOS want more information about the condition and its management, including lifestyle management.12 It is important that health professionals working with these women are informed of the evidence-based guidelines and are prepared to answer questions and provide information and support that women need to help in managing their condition.

As part of the translation tools for the new evidence-based guidelines, a PCOS question prompt list was developed, in conjunction with women with PCOS, to help guide them in the questions they may want to ask their doctor or other health professionals.19

In an online survey of 249 women with PCOS, more than two-thirds reported difficulty communicating with healthcare providers about mood, weight management, and how PCOS affects daily life, and the majority (86%) indicated they were very likely to use a PCOS prompt list.19

When pilot-tested, the majority of women agreed the tool was helpful and that they would use the tool again (95% and 90%, respectively).19

The prompt list is now available for women with PCOS to use, and being familiar with the lifestyle-related questions within the tool may help health professionals to understand the types of questions these patients might have and to be prepared to answer them when asked.

These questions include:

• Is lifestyle management better for my PCOS than medication or surgery?

• Do I need to follow lifestyle management as well as medication or surgery?

• Why is lifestyle management a good option or not a good option for me?

• Do I need to maintain my current weight?

• Do I need to lose weight?

• How much weight should I aim to lose?

• How long will it take to lose this amount of weight?

• Can a better diet improve my PCOS?

• Is there one best diet for PCOS?

• What is a low glycemic index (GI) diet?

• Should I avoid certain foods (like sugar) completely?

• Which health professional should I see for more support about how to have a healthy diet?

• Do I need to be more active or exercise more?

• Is there one best type of physical activity or exercise for PCOS?

• I don’t like gyms (or exercise classes or weight training), are there other activities I can do?

• Which health professional should I see for more support about physical activity or exercise?

Providing evidence-based information and tools to women with PCOS can also help to meet their need for relevant and accurate information about their condition.

Dr Kate Marsh is an Advanced Accredited Practising Dietitian, Credentialled Diabetes Educator and Health and Medical Writer working in private practice in Sydney, with a particular interest and expertise in the nutrition and lifestyle management of PCOS. www.drkatemarsh.com.au

References:

1. Gilbert EW, Tay CT, Hiam DS, Teede H, Moran LJ. Comorbidities and complications of polycystic ovary syndrome: an overview of systematic reviews. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). August 2018. doi:10.1111/cen.13828.

2. Lim SS, Davies MJ, Norman RJ, Moran LJ. Overweight, obesity and central obesity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2012;18(6):618-637. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms030.

3. Lim SS, Norman RJ, Davies MJ, Moran LJ. The effect of obesity on polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14(2):95-109. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01053.x.

4. Haqq L, McFarlane J, Dieberg G, Smart N. The Effect of Lifestyle Intervention on Body Composition, Glycaemic Control and Cardio-Respiratory Fitness in Women With Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2014;25:25.

5. Haqq L, McFarlane J, Dieberg G, Smart N. Effect of lifestyle intervention on the reproductive endocrine profile in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocr Connect. 2014;3(1):36-46. doi:10.1530/EC-14-0010.

6. Moran LJ, Hutchison SK, Norman RJ, Teede HJ. Lifestyle changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD007506. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007506.pub3.

7. Teede HJ, Misso ML, Costello MF, et al. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018;89(3):251-268. doi:10.1111/cen.13795.

8. Teede H et al. on behalf of the IPN. International Evidencebased Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Melbourne Australia; 2018. https://www.monash.edu/medicine/sphpm/mchri/pcos/guideline.

9. Avery JC, Braunack-Mayer AJ. The information needs of women diagnosed with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome – implications for treatment and health outcomes. BMC Womens Health. 2007;7(1):9. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-7-9.

10. Humphreys L, Costarelli V. Implementation of dietary and general lifestyle advice among women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J R Soc Heal. 2008;128(4):190-195.

11. Dokras A, Saini S, Gibson-Helm M, Schulkin J, Cooney L, Teede H. Gaps in knowledge among physicians regarding diagnostic criteria and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(6):1380-1386.e1. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.04.011.

12. Gibson-Helm M, Teede H, Dunaif A, Dokras A. Delayed diagnosis and a lack of information associated with dissatisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;102(2):jc.2016-2963. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-2963.

13. Ching HL, Burke V, Stuckey BG. Quality of life and psychological morbidity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: body mass index, age and the provision of patient information are significant modifiers. Clin Endocrinol. 2007;66(3):373-379.

14. Teede HJ, Joham AE, Paul E, et al. Longitudinal weight gain in women identified With polycystic ovary syndrome: Results of an observational study in young women. Obesity. 2013;2(10):20213.

15. Kataoka J, Tassone E, Misso M, et al. Weight Management Interventions in Women with and without PCOS: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2017;9(9):996. doi:10.3390/nu9090996.

16. Lin AW, Dollahite JS, Sobal J, Lujan ME. Health-related knowledge, beliefs and self-efficacy in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(1):91-100. doi:10.1093/humrep/dex351.

17. Benham JL, Yamamoto JM, Friedenreich CM, Rabi DM, Sigal RJ. Role of exercise training in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Obes. 2018;8(4):275-284. doi:10.1111/cob.12258.

18. Lee I, Cooney LG, Saini S, Sammel MD, Allison KC, Dokras A. Increased odds of disordered eating in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord – Stud Anorexia, Bulim Obes. June 2018. doi:10.1007/s40519-018-0533-y.

19. Khan NN, Vincent A, Boyle JA, et al. Development of a question prompt list for women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2018;110(3):514-522. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2018.04.028.