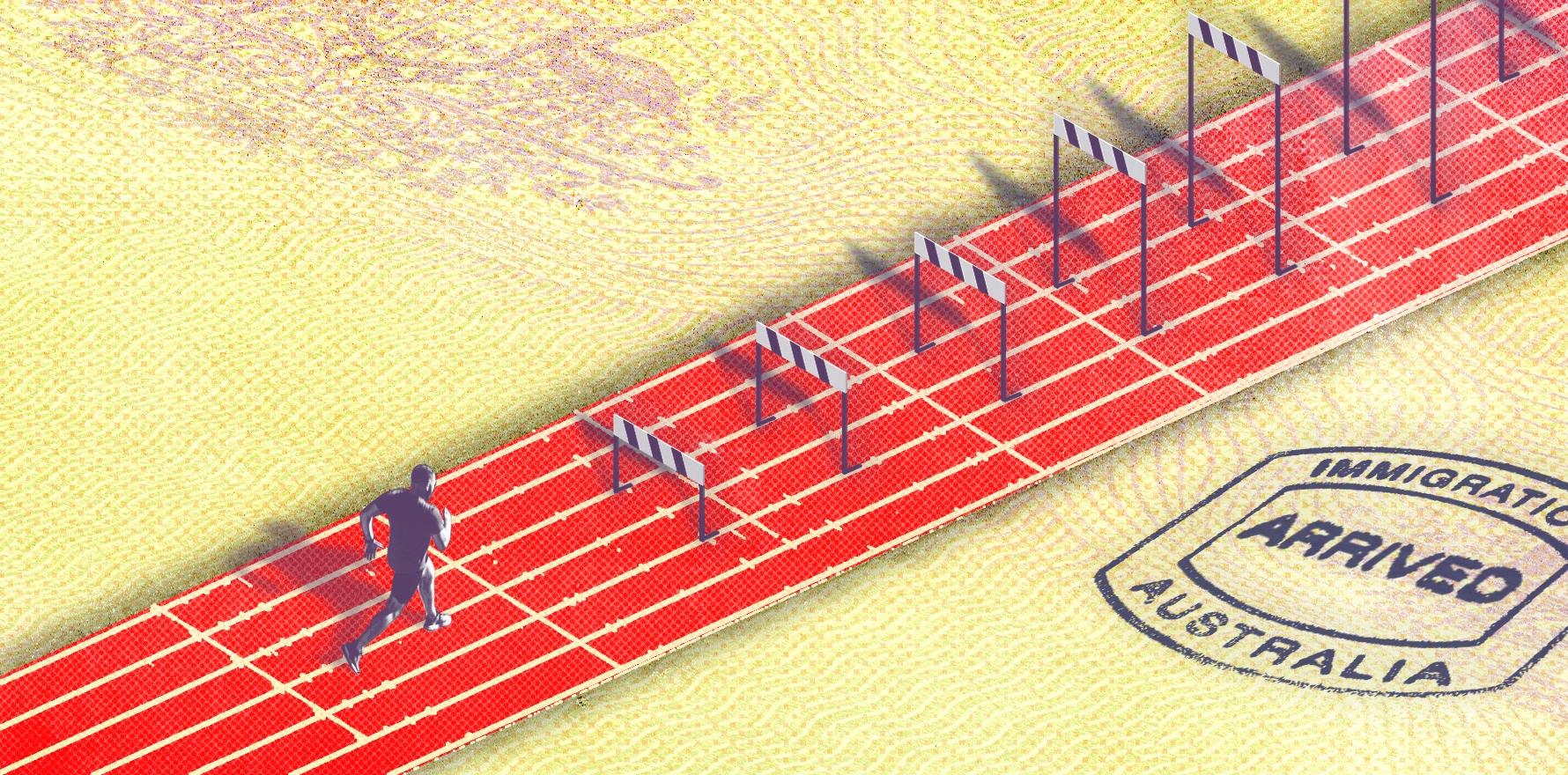

IMGs are essential to our workforce but they must navigate a rigid, difficult system with little support and no allowance for life’s surprises.

Dr K has worn many medical hats.

In Pakistan, he was a cardiothoracic surgeon.

When he moved to Australia in 2007, he became a father for the first time. Almost 30 and not wanting to miss his daughter’s childhood, he opted to do an emergency medicine fellowship rather than go back through surgical training.

When his wife, also a doctor, was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer, he had to scale back his night and late afternoon shiftwork. Unable to complete the last stretch of emergency medicine training, Dr K became a GP registrar.

When he failed the RACGP’s key feature problem exam the first time, it wasn’t necessarily a surprise. His wife, after all, was still sick; there was a lot of pressure on him in his personal life. Besides, he had passed the applied knowledge test and the remote clinical exam on his first attempts.

Then he failed again. And again. And again.

Dr K failed the KFP nine times.

Then he had a heart attack.

The system

Dr K, who asked us not to use his real name, is just one of around 33,000 Australian doctors who did their primary medical training overseas.

The Australian medical system, rural general practice in particular, is built off the back of skilled migrants like Dr K and his family.

According to ACRRM statistics, around 40% of doctors in small regional or rural centres were trained overseas, but the RACGP and Rural Workforce Agency Network peg the proportion of international doctors working in rural or remote regions at upwards of 50%.

Despite Australia’s reliance on IMGs, we hardly roll out the welcome mat.

“The system is too difficult for applicants to navigate,” senior public servant Robyn Kruk notes in the interim report of her independent review of overseas health practitioner regulatory settings.

“Requirements and processes are duplicative and inconsistent.

“The same or similar information is often provided to multiple agencies.

“Applicants report they receive little or no support navigating the process.”

This rigid and demanding system means that if things start to go off plan in an overseas-trained doctor’s personal life – like getting out of an abusive marriage or taking care of a sick family member – they often get left out in the cold.

Extenuating circumstances

It’s this feeling, that the institutions meant to support you are not in your corner, that’s been the most painful for Dr K.

Throughout the three years he spent trying to pass the KFP, there have been multiple other complications in his personal life.

Firstly, his wife was still going through chemotherapy for her breast cancer.

Then, while visiting Australia, Dr K’s mother developed blood clots. She was put on blood thinners and ultimately ended up with an internal bleed that required surgery.

As a non-citizen, Dr K’s mother’s care was a financial burden.

It was at around this time that Dr K stopped working in general practice completely, choosing to take up locum work instead.

Even as Dr K’s mother and wife gradually returned to health, other things started going wrong.

One of his brothers in Pakistan developed cytokine release syndrome following a covid infection and spent 25 days in the ICU.

The travel restrictions in place meant he was unable to lend any assistance to either his brother or his father, who was left taking care of two children alone.

Then Dr K’s brother-in-law died of covid. So did one of his cousins.

Throughout this time, he was still repeatedly sitting the KFP.

The odds were stacked against him, although he might not have known at the time – statistically, when it comes to RACGP exams, pass rates decrease with the number of attempts.

Feedback is only given via public reports, not at the individual level.

The questions are also all renewed each exam and each exam cycle, meaning it is theoretically unlikely for someone to be failing on the same question twice.

“Our advice to candidates is to use the public report to reflect on the exam and consider areas where they may be able to improve,” college CEO Paul Wappett tells TMR.

“Rather than seeing this as a failure, it is instead an opportunity learn and grow and apply those learnings when trying again.

“Exam technique is also important, and the public reports reiterate areas that candidates need to take particular note of.

“Again, this is something that candidates can take on board and use to improve their knowledge and expertise.”

Less than a month before he was due to sit his most recent attempt, Dr K received an email alerting him that his name had been removed from the examinations list because the pathway he was on was no longer funded.

While a letter had been sent to ineligible candidates like Dr K the month before, he had missed it.

Commonwealth funding for the Practice Experience Program ended in June 2023 and it was replaced by the self-funded Fellowship Support Program, which comes at a total cost of $32,000.

Registrars only have to pay one semester at a time, but the sum was significant to Dr K.

“They banned me from appearing in the [KFP] exam until I [agreed to] pay them that $32,000 and until I go for another two years of training [in a rural area],” he says.

Dr K joined the FSP, even though it would require him to work in an MMM2 – 7 region.

Not long after, Dr K woke up in the early hours of the morning with chest pain.

His right coronary artery was completely blocked.

He keeps fit, regularly going on 10km runs, and he has no family history of heart disease.

Dr K can’t prove it, but he strongly feels that the stress of trying to navigate the system was a contributing factor.

Empathy

While he was in the coronary care unit, Dr K contacted the college to request an exemption on medical grounds that would allow him to undertake the FSP while living in a metro area.

He says he received conflicting communication from the college, which repeatedly contacted him while he was still in the CCU asking him to submit paperwork.

“I understand this is routine for those in administration, but whilst I was in the CCU I felt a bit of sensitivity would have helped,” Dr K says.

His wife ended up stepping in.

“In the CCU they were sending me messages saying ‘you should send [this or] that document by 4pm tomorrow’,” Dr K says.

“My wife became really, really angry and then … she started speaking to the college saying, ‘please stop sending these messages on his mobile phone. Please. He’s in the CCU right now.’”

For what it’s worth, the college says it is committed to providing strong support to candidates who don’t initially pass exams.

“We realise that all candidates face their own circumstances and challenges and some people do need a helping hand to improve their results,” Mr Wappett says.

“The type of support varies depending on the circumstances of the person involved and we ensure that the help we provide is appropriate to their needs.

“Not succeeding in the fellowship exam the first time may be discouraging, but that certainly does not mean that achieving fellowship is unattainable.”

Dr K says the RACGP continued to send emails, despite his wife’s request.

The request for exemption was knocked back on the grounds that neither Dr K nor his wife were sick enough.

So he decided to quit.

“I want to live for my children, at least,” Dr K says.

“Being alive is more important than having a fellowship.”

Somewhere in his KFP examination prep material, Dr K has notes on the importance of empathy as a doctor.

“Where is the sympathy and empathy after having done nine attempts with no one contacting me, asking ‘what’s happening’?” he says.

“And where was the sympathy and empathy when I was in the CCU?”

It’s not that he wants the college to give him a free pass or an easier go – he just wants to feel like more than a source of fees.

Epilogue

Right now, Dr K is contemplating restarting an emergency medicine fellowship.

He’ll have to train for another three years before he can sit the exit exams, but he’s prepared to wait.

Dr K’s wife is in remission from her breast cancer.

Their two children have decided not to pursue medicine.