Who will win out of obesity and diabetes in the Ozempic debate? And welcome to a new world of tax pain for GP contractors.

There are a few things to talk about this week, but don’t worry! The editor is away, and the stand-in is scary and not allowing a word over 2000, so I’m crazily summarising here (crazy for me).

The first topic is more a news story than opinion because no one has reported it yet, but it’s worth alerting everyone that the ATO released a draft ruling in late December. This ruling seems to put individual contract doctors on the spot, in a similar way to how the QRO payroll tax ruling has put a lot of practice owners in a jam.

Instead of a payroll tax problem, the ruling – Draft taxation ruling TR 2022/D3 – poses a potential income tax problem for any doctor who is a contractor, so the ATO is coming at the employee-contractor issue from the other end of things.

The ruling is laying down some ideas around what the ATO feels constitutes an employee as opposed to a contractor, and those ideas are a lot tighter in interpretation than the ATO has ever provided before. I specify “ideas” because a ruling, especially a draft one, is not law and often, as in the case of the QRO ruling, is published with some intent to stir a pot and see what comes of it.

The bottom line, according to our friendly in-house tax problems watcher and HealthAndLife Advisory principal, David Dahm, is that if the draft ruling did end up as law then there would probably be a lot of contractors (or tenant doctors working for service entities) who would need to have a much better look at the various components of their personal set-up (their contracts, their own company structures, how they present themselves to the public, et al) to ensure they are ATO compliant.

Right now, you’re thinking “OMG, governments, what is going on with tax and doctors? Are you not happy with the chaos you’ve rained down on us via payroll tax?” But, the ruling is not directed at doctors per se, it’s directed at everyone who rolls as a contractor. Doctors just happen to fall into the category of professions who work as contractors a lot.

Dahm, who has already written about the ruling on his website HERE (warning: he’s more long-winded and confusing than I am), told TMR that there are upsides.

“In one respect the ruling may be good for GPs because now both the tenant doctor and their landlord [the practice owner using a services entity structure] have to align in getting compliant on tax and if they do, and get their structures aligned to both tax bodies, then this whole horror-show should start to settle down over time”.

Dahm says that the detail, like payroll tax, is probably going to require some proportion of tenant doctors to seek professional accounting and even legal advice.

One interesting aspect of the new ruling is that the ATO is more or less asking a doctor’s accountant to sign off on their client as being compliant or not.

This is an insidious but effective tactic on the part of the ATO.

Accountants don’t like to sign off on anything.

But if you can get your accountant to agree that you are compliant according to this ruling then you can be pretty sure that you are, because accountants won’t do it lightly. So, there’s a personal business goal for you if you are a tenant doctor over the next year or so: get your accountant to put their reputation where their money is.

Once you get your accountant to do this then you will have earnt yourself a spot in what the ATO terms “safe harbour”.

Nothing is guaranteed where tax is concerned, but when you’re at that point you can probably move on to more important things in your life, like treating vulnerable patients, with some sense of security. Safe harbour is like an ATO compliance tick.

We will report in a little more detail on this ruling this coming week.

Bulk billing ain’t dead but it has changed forever

Given the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce steered almost entirely clear of committing any money to GP rebates, at least in the near term, it’s worth reading this week’s analysis of the emotional and practical implications of GPs’ now steady shift towards private billing by Dr Imaan Joshi.

Dr Joshi points out something that should be obvious by now, but which you suspect the government still may not have realised entirely: bulk billing as we knew it, and as the government originally intended, is over and never coming back now GPs have seen the other side.

According to Dr Joshi: “Those who have moved to private billing are all saying, ‘I wish I’d done it sooner’, and ‘there is no amount of rebate the government could offer that would tempt me to return to bulk billing (everyone)’”.

In other words, even if the government did what the RACGP and the AMA were asking and tripled rebates tomorrow, the mixed billing habit is here to stay and the high rates of bulk-billing we’ve all been used to over the years will never again be seen in our system.

Sorry Gough.

You can read it as the government having stuffed up far more than they realise or, as Dr Joshi seems to, that GPs have actually been emancipated by the government forcing them to do what has historically and culturally always been counterintuitive to them. That is, charge people who can afford it (and even some who can’t) more than the government is prepared to rebate their patients.

Dr Joshi points out that slowly but surely the traditional public view (or misconception) that GPs are paid to keep healthcare free for everyone is breaking down and that although a disturbing emotional process, once we get to the other side of this public education process, everyone will be better off for it.

“Is it so strange that the public sees us as public servants, and that the nuance between patient rebate and GP wage has been lost? When you have not had to get your wallet out in 40 years, is it not understandable you think your taxpayer dollars pay for our wages, like ED and public hospital staff?” asks Dr Joshi.

As if to reinforce some of Dr Joshi’s arguments, a Canberra-based GP practice with, presumably, a lot of DVA clients stepped into what would normally be terrifying public reputation territory. It announced this week that it would no longer be honouring DVA white cards (which pump up most items by 15% for a vet). That story is HERE.

The bottom line for this Canberra practice is that the veterans rebate is simply not enough to keep their practice viable. So they sent a letter to all their vet clients and explained the situation.

Can you imagine doing that even a couple of years ago?

“Diggers” are, in the eyes of the public and the government, a special breed of sacred (although from a government perspective that might be more in words than actions).

It will be interesting to see what happens if some of the loony right-wing press get hold of the story: “Greedy doctors abandon our diggers” is a headline you can imagine.

But if you follow Dr Joshi’s logic, such a headline might be the price GPs need to pay to get the public to wake up to the fact that GPs are small businesses going broke and they are getting pretty desperate.

How different really is the process of saying, “Sorry diggers, we can’t afford it”, to saying, “Sorry pensioner, child, obviously financially distressed patient, we can’t afford it” which is what’s starting to happen a lot everywhere now.

Diggers get in line, in other words.

None of this is to say that increasing rebates should not and will not be something important in reforming the system and strengthening primary care in the future.

Increasing rebates substantively is going to help things a lot: it will give practices like this one in Canberra the chance potentially to return to their 115% rebate, and give GPs all over the country far more ability to help out vulnerable patients where they can.

It’s just that now, GPs will probably never be so stupid as to return entirely to a bulk-billing model and let the government dictate terms via a public perception that healthcare is free – and so is your GP (an idea that, long ago, the government decided it was not prepared to fund).

Now, those in the profession who are on the other side of mixed billing know that a mixed model is the right model, and it’s the balance of that mix that they will be able to dictate, if the government ever does return to properly funding the patients of general practice.

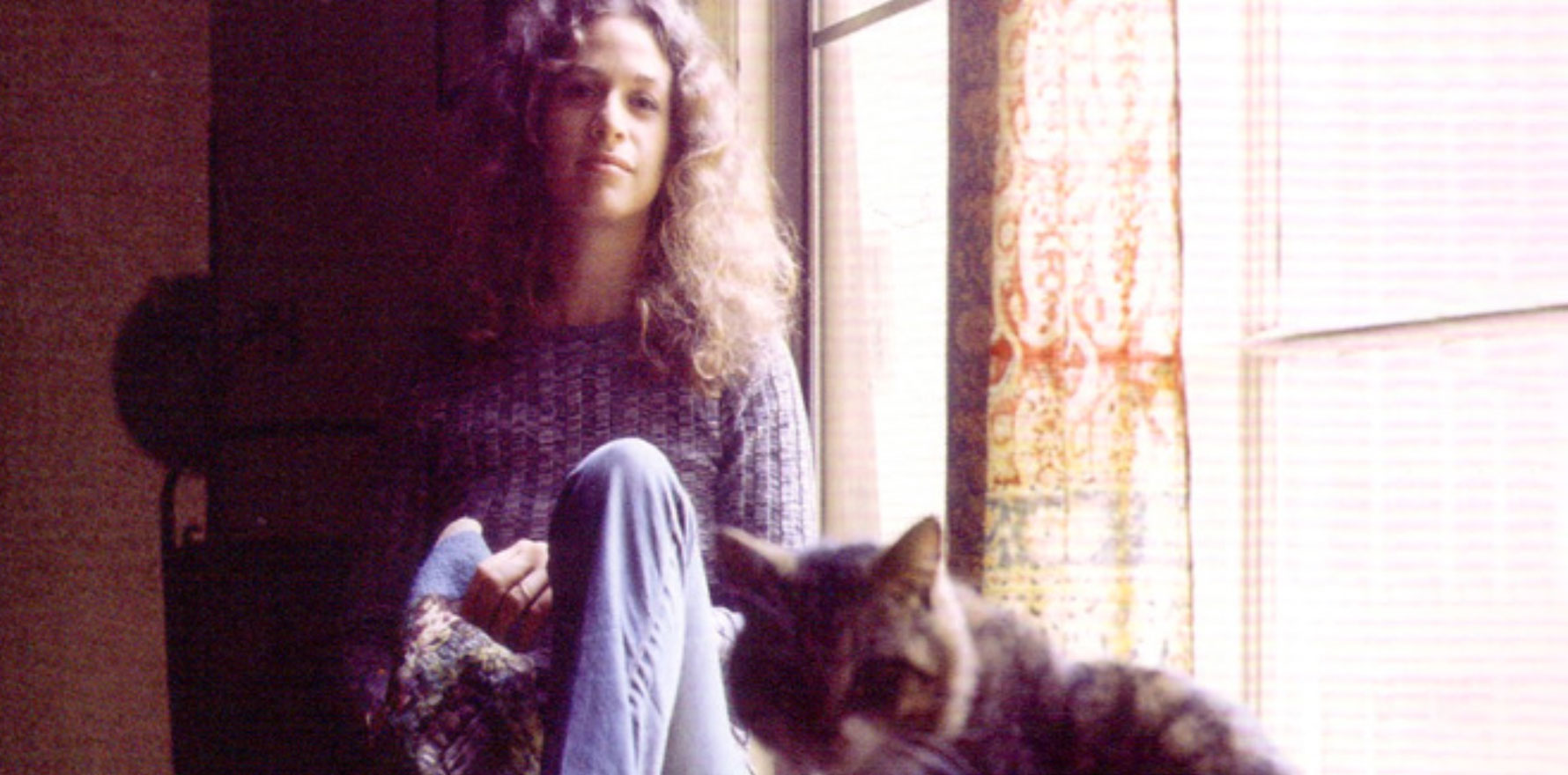

Carole King comes to mind here in terms of where the government finds itself, although it may not have fully realised it yet:

And it’s too late, baby, now it’s too late

Though we really did try to make it

Somethin’ inside has died

And I can’t hide and I just can’t fake it

To take the reputational risk of denying diggers cheaper healthcare, something really has died in that Canberra practice and I doubt they are faking it.

The broader implications for Medicare reform and the Strengthening Medicare Taskforce could not be more wide-ranging.

Medicare isn’t Medicare now. Even if the government did want to go back to the old days and make it all free, they can’t. They’ve killed Medicare, at least as it was conceived.

And the public is only now just catching up on that fact.

Medicare 2.0, if we can get there, is going to take a lot of smart thinking and much better public engagement to get over the line.

Who deserves to get Ozempic?

One more reading recommendation for this week in case you missed it: Who deserves Ozempic, anyway?

This story poses a series of fascinating medical, regulatory and ethical questions for the modern GP, and possibly for modern medicine in general:

- Who decides what a drug should be used for when a drug can do more than one thing, but one of those things is yet to be formally sanctioned by the authorities?

- Is obesity a disease you need to treat to avoid many other diseases as a priority over some of those other diseases, including type 2 diabetes, which is what Ozempic is PBS-approved for in Australia?

- Why do doctors have to make these decisions on behalf of their patients and risk possible blowback from various regulators if they get the decision wrong?

- Why do we still not have a good handle (including decent updated guidelines) on the science, treatment and general approach to obesity?

Holly Payne takes us on a fascinating journey through these questions with views from various stakeholders, right down to the ethical clanger: when a drug like Ozempic is in short supply, who do you choose?

According to Payne, the crux of these dilemmas comes down to the way obesity and weight loss are perceived, both medically and on a social level.

“Despite mounting evidence to the contrary, obesity is still often seen as a lifestyle choice or inherently linked with negative personal attributes like laziness and greed,” she points out.

But this attitude, and evidence around obesity as a disease, seems to be changing quite rapidly.