The changes are a capitulation, not a revolution, according to the chair of the Mild Asthma Working Group which reported to Asthma Guidelines committee, Dr Russell Wiseman

It’s been touted as the biggest change to asthma management in 30 years, but at least one Australian expert says PRN budesonide-formoterol is no revolution – it just represents a failure to educate patients and GPs about daily prevention.

The new Asthma Handbook for Australian practitioners previewed last week recommends mild asthmatics use the combination inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta agonist (Symbicort 200/6 Turbuhaler and 100/3 Rapihaler) as needed, in line with the Global Initiative on Asthma strategy. Changes to the PBS effective from June 1 mean this regimen is subsidised for the first time.

The overuse of SABAs, which large trials have shown to put patients at higher risk of exacerbations, is common in Australia where the SABA salbutamol (Ventolin) is cheap and available over the counter. Experts have been raising the alarm about the use of bronchodilators without anti-inflammatories, some going so far as to call the familiar blue puffer a “killer”.

At the virtual OPC event Air Time on Saturday, chair of the Asthma Handbook guidelines committee Professor Amanda Barnard explained the changes and committee member Professor Peter Wark of Hunter Medical Research Institute outlined the research behind them.

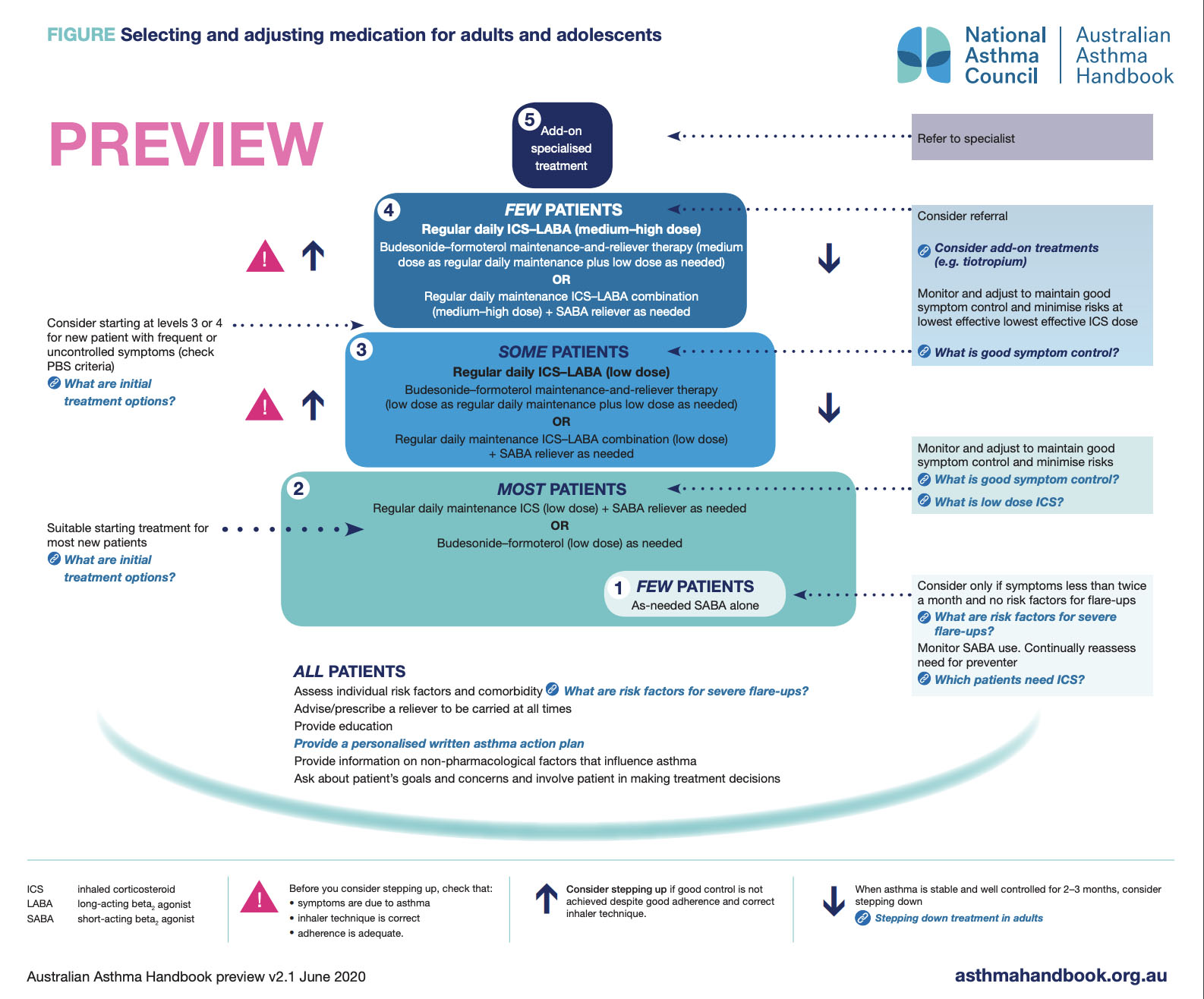

The new diagram for primary care of asthmatics keeps the five-step structure, in which step 1 is SABA as needed for extremely rare symptoms and step 5 is refer to specialist for add-on therapies such as biologics.

Step 2, which applies to “most patients”, now contains low-dose budesonide-formoterol as needed as an alternative to “regular daily maintenance ICS (low dose) + SABA reliever as needed”.

The addition of as-needed budesonide-formoterol in a single inhaler for mild patients is a kind of compromise that aims to reduce the number of severe attacks while being easier to adhere to than the ideal, which is daily preventer ICS and reliever as needed.

The event’s chair Professor David Price – board member/editor of Allergy & Respiratory Republic, among his many titles – described what he called “the Australian challenge” using data on exacerbation rates by severity.

“What you see is the rates of severe asthma exacerbations are rather lower in the UK, especially in step one and step two [the mildest patients], and I suspect that may well relate to the availability of salbutamol OTC here in Australia,” he said.

Professor Barnard said too many asthma patients were on only SABAs and too few were on daily ICS.

But drug adherence in mild asthma posed a unique problem. Sick patients in general were easily convinced to take medication to make them feel better, and asymptomatic hypertensive patients were scared enough of the consequences to take their prescribed drugs; but asymptomatic asthma patients fell somewhere in between and couldn’t see the point of daily medication.

Professor Wark said “mild” asthma was a misnomer, as it still put people at risk of serious outcomes.

Higher use of SABAs was associated with higher risk of emergency presentations (three or more canisters per year) and of death (12 or more), he said. In Australia, 74% of asthmatics failed to adhere to regular ICS treatment.

He said overuse of formoterol was also potentially dangerous, which was why a written action plan was so important. Patients shouldn’t exceed 72 micrograms daily, corresponding to 12 puffs of the 200/6 inhaler or 24 puffs of the 100/3 inhaler.

Professor Wark said it was crucial in every patient to confirm the diagnosis of asthma, ensure compliance with therapy and effective technique, treat factors that worsen asthma control, use a written action plan and refer onwards if control is not achieved.

He cited large trials showing as-needed ICS-SABA reduced the number of severe exacerbations by the same amount as daily preventer use, though the latter was slightly better at maintaining day-to-day control.

But Queensland GP Dr Russell Wiseman, founder of the General Practitioner Asthma Group, said the effect of the new guidelines was to “dumb down” the treatment of asthmatics.

He said his concern when the changes were first floated was that people with a new diagnosis of asthma would be put straight on the new regimen.

“I spend a lot of time un-diagnosing asthma,” he said. “I find that a lot of our people who present with tightness and wheeze, six to 12 months or two to three years down the track, actually turn out not even to be asthmatic.

“My fear was that a new patient would just be put on PRN bud-form, never reviewed and let loose on the community. I’m worried that the whole process attempts to dumb down the treatment of asthmatics and I’m worried that we’ll forget the proper assessment of the symptoms.

“And, you know, bud-form patients will be just as non-compliant, just as non-adherent and have just as poor technique as [those on] any other regimen that we’ve ever tried or invented.”

Dr Wiseman said the profession was sacrificing symptom control and lung function “on the twin altars of ‘no SABA’ and severe exacerbations”.

“I do not think it’s the biggest revolution in 30 years in asthma – that’s a GINA perspective. It’s a new option. But I think we’ve got to keep it in context.

“And I think we’ve failed in the last 30 years to sell the regular mono-ICS story to patients. We’ve tried to do the education to GPs and to patients using too-medicalised terms – we’ve not got the message across in such a way that the lay patient could really understand what control is, what preventers are all about. So I think there’s lots of challenges in front of us.”

Professor Wark conceded that the profession “could well have delivered the education better”.

“But it is difficult to get away from the concept that for people with fairly intermittent symptoms, it may not be something that we’re ever going to be able to sell them [on], to take a medication regularly,” he said.

At the end of the event Professor Price asked the panellists, on behalf of an audience member: given that inhaled corticosteroids take time to work, when a patient inhales the combination for immediate symptom relief, is it only the formoterol that’s working?

Professor Barnard confirmed that was the case.

“But the point is that the people are getting some steroids as well,” she said.

“If they’re getting symptoms three times a week and they’re using budesonide-formoterol, they’re getting a small dose of steroids, which is going to do something for the underlying inflammation. So you do reduce flare-ups and exacerbations.

“But it’s not an absolute panacea or the right thing for everybody – some people are going to do better symptomatically if they take regular steroids.”

Given the lethality of thunderstorm asthma for susceptible patients – worse in those only using bronchodilators – they should use ICS every day in the lead-up to pollen season.

Professor Price agreed that the combination model was about getting a build-up of steroids.

“Regular ICS should be the norm, but this is a good strategy for the more intermittent and those who won’t take it regularly,” he said.

Dr Wiseman had the final word, saying that in the SYGMA trials that formed much of the evidence base for the changes no treatment arm reached clinically important difference for symptom control, and the daily preventer message was not really that hard to reinforce.

“Just take it [ICS] once a day when you clean your teeth – it’s a good each-way bet,” he said.

More information:

https://www.nationalasthma.org.au/news/2020/australian-asthma-handbook-2-1-update