The NDIS has good intentions, but it doesn't seem to support the unique needs of Indigenous people living with a disability in remote areas

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with severe disability face many barriers to fully accessing the support offered by the NDIS. This group of people has already experienced long-standing isolation and are particularly vulnerable to being left behind, again.

The prevalence of disability among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is twice that experienced by other Australians. It is more complex in terms of more than one disability or health issue occurring together, and it is compressed within a shorter life expectancy.

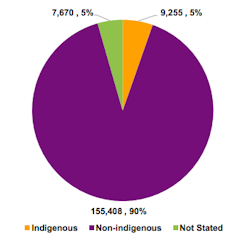

The latest NDIS quarterly report states 9,255 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are participating in the NDIS (roughly 5.4% of the total). Though, being a “participant” means they have been signed up to an insurance policy. It doesn’t necessarily mean the policy has been paid out. And many others aren’t on the scheme at all.

There are an estimated 60,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across Australia with a severe or profound disability. In 2014-15, around 45% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15 years and over said they experienced disability – 7.7% of whom needed assistance with core activities some or all of the time.

My recent research shows Indigenous people who live with disability experience far greater inequality when it comes to social, health and well-being, compared to other population groups. This includes Indigenous people without disability, and people with disability who are not Indigenous.

Many struggle with basic survival needs

My research consisted of statistical data and the personal testimonies of 47 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. It showed the NDIS isn’t accommodating the unique needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability.

People in one Aboriginal community said while the NDIS was providing support packages – in some cases at around A$50,000 per person per year – these were not translating into actual expenditure as there weren’t any disability services in the community that NDIS participants could purchase.

Members from another Aboriginal community pointed out that some families needed food and blankets because they were homeless and hungry. But while the NDIS is legislated to provide “reasonable and necessary” supports, food and blankets don’t meet the requirements of the definition. As one Aboriginal community Elder said:

Swags and blankets are something that our families ask for all the time, help with making sure that they’ve got somewhere warm and safe to sleep, and that’s a real practical thing […] And now the NDIS is saying ‘No, we don’t buy swags and blankets for people. That’s not reasonable and necessary’. But if you’ve got nowhere to sleep, of course blankets and swags are necessary.

In another community, wheelchairs provided to people with a mobility impairment weren’t suitable for an environment with no footpaths and where the heat can sometimes melt away the tyres.

We also spoke with people who said the houses built for them under a remote housing scheme didn’t have disability access in mind.

These cases highlight an unfolding design fault of the NDIS: if a person with a disability doesn’t have survival basics, the scheme falls short in its capacity to ensure the choice, control and independence it was set up to achieve for people with disability.

Read more: The NDIS is delivering ‘reasonable and necessary’ supports for some, but others are missing out

Social policies must work together

Proponents of the NDIS might point out it is designed as an insurance scheme and not intended to provide welfare. Basics such as blankets and food would be more the purview of the Closing the Gap framework to address Indigenous disadvantage.

But the NDIS and Closing the Gap live on two separate government islands, with no bridge in between. The NDIS is a market-based scheme devoid of a strategy that fills the gaps in basic public structure that make markets work. Nor does it have a plan to develop a workforce to meet the demand for disability services in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Meanwhile, despite the link between disability and social inequality, there is no reference to disability in any of the Closing the Gap targets.

Addressing the core public infrastructure needed to make the NDIS work in remote communities, or developing the workforce to meet the demand for disability supports in the hard-to-reach markets are not quick fixes. We need a longer term strategic approach that focuses on community development to overcome the sustained inequality that comes with being both Aboriginal and living with disability.

PhD student, University of Technology, Sydney

Disclosure:

Scott Avery received research funding funder the National Disability Research Development Agenda jointly implemented by Commonwealth, state and territory governments, and from the Lowitja Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health for this research. He is the Research and Policy Director at the First Peoples Disability Network (Australia), a community-based Indigenous disabled peoples organisation.

This blog was originally published on The Conversation