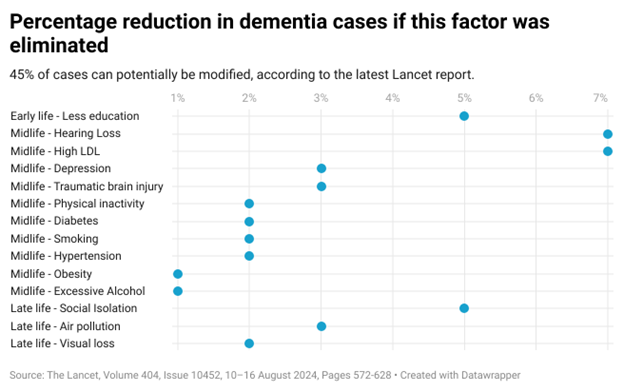

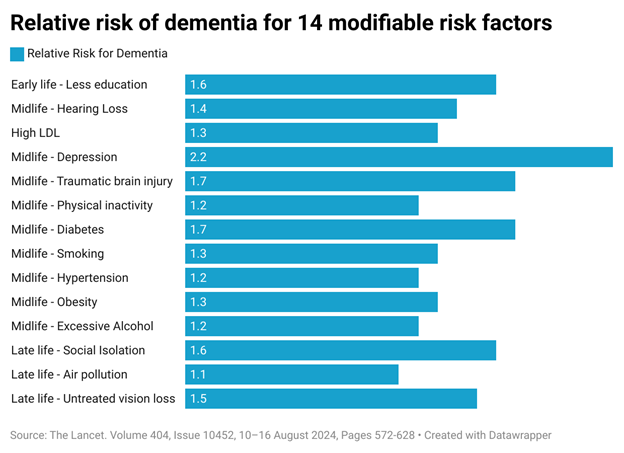

Nearly half of cases could be delayed or avoided with attention to all the modifiable risk factors, researchers say.

Fourteen modifiable risk factors for dementia have now been identified, some of them starting as early as childhood, with the potential to prevent or delay almost half of all cases.

The Lancet Commission on dementia prevention has previously listed lower levels of education, hearing impairment, high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, depression, physical inactivity, diabetes, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, air pollution and social isolation.

In its third update, the commission has added two more. It says 2% of cases could be attributed to untreated vision loss later in life and 7% to high low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in mid-life, from around the age of 40.

As populations age, the rates of dementia globally are expected to triple by 2050. But rates in some wealthy nations are going in the opposite direction in older people with higher incomes who have access to preventative measures, the commission says.

Addressing these modifiable risk factors as early as possible can affect development of dementia, even in cases where there is a family history. However, causality depends on context, it cautions, and addressing risk factors affects populations, with no guarantee for individuals.

The report uses the latest available data and makes 13 recommendations for individuals and governments to address these 14 modifiable risk factors:

Provide education to all children and be cognitively active in mid-life

Research shows that stimulating work and educational attainment are associated with lower dementia risk, which the authors say could build cognitive brain reserve that enables individuals to withstand neuropathology.

“Notably, short-term computerised cognitive training interventions at low intensity, which can be financially costly, have only low-quality evidence of short-term effectiveness and no evidence of long-term effectiveness in maintaining cognition,” they add.

Prevent and treat hearing loss with hearing aids and reduced noise exposure

The association between hearing loss and dementia risk is dose-dependent, with risk increasing between 4% and 24% for every 10dB decrease in hearing ability, according to the latest analyses. But wearing hearing aids significantly reduces that risk. This could be because hearing impairment affects social interaction, reduces stimuli, and requires a person to use more cognitive resources, the authors write.

“Another postulated mechanism is common cardiovascular pathology, whereby vascular disease affects the cochlea or the ascending pathway, causing hearing loss, and the medial-temporal lobe, causing dementia.”

Screen for and treat vision loss equitably

“Our Commission has not previously considered vision loss as a risk factor for dementia, but considerable new evidence has emerged,” the authors write.

In some studies, vision loss is associated with a 35-47% higher risk of dementia compared to people with intact vision. Some evidence shows the risk increases with cataracts and diabetic retinopathy, but not with glaucoma or age-related macular degeneration.

Treatment seems to reduce the risk. A study shows a 29% risk reduction in those who had cataract extraction compared to those who didn’t, and another found no difference in risk between those who had the surgery and those with no cataracts to begin with.

The risk could be due to vision loss itself, underlying illness, or neuropathological pathways shared by the retina and the brain, the authors say.

Treat depression

People with depression across the across the adult years have more than double the risk of developing dementia, according to the commission’s analysis. Some later-life depression could be caused by preclinical dementia but midlife depression is a clear risk factor.

Although the reasons are unknown, it’s been suggested that depression might lead to lower self-care and social interaction. It might also be due to an inflammatory response or hippocampal atrophy from oversecretion of cortisol.

“[F]indings on the effect of medication and therapy for depression in reducing the risk of dementia suggest the importance of treating depression both for quality of life and because it might reduce the risk of dementia in the future,” the paper says.

Encourage participation in exercise and sport

“We previously concluded that the balance of evidence is that the link between exercise and dementia is likely to be bidirectional,” the authors write. But since then, research has shown that exercise decreases the risk of dementia by around 20%, regardless of when people start exercising. This might be because of changes to blood flow and function from lowered hypertension and increased nitric oxide leading to lower neuroinflammation and increased brain plasticity.

“Outcomes might depend on not only the duration but also the type and intensity of physical activity,” the authors write.

“People who engage in moderate-to-vigorous exercise on more days have relatively larger brain volumes than those who do less or no exercise. Evidence from mouse models also suggests that irisin, a myokine released during exercise, might be neuroprotective.”

Wear a helmet in contact sports and cycling

Traumatic brain injury, especially before the age of 65 and in men, brings dementia onset forward by two to three years, research has shown. Two recent meta-analyses found an increased risk of 66-81%. Even a single mild traumatic brain injury could increase risk by around 60%, according to a Danish population study.

Dementia could be caused or exacerbated by direct trauma to the head, including axonal injury promoting early generation of proteinopathies (hyperphosphorylated tau and amyloid β), cortical atrophy and microglial activation, the authors said. But they warn this should not stop people from playing sport, which is, on the whole, good for them.

“Protection from head injury, for example, by appropriate head protection equipment, limiting heading practice and high-impact collisions, preventing playing immediately after TBI, and possibly adaptation of the rules to limit injury, should now be an individual and public health priority,” they write.

Increase social contact with supportive communities and age-appropriate housing

Evidence continues to show that social isolation is linked to developing dementia. Depending how it is measured, social isolation is estimated to increase the risk by 14% to over 50%. Socially isolated people also have less grey matter.

Studies looking specifically at loneliness and lack of participation in social events find a correlation with dementia. Many trials continue to investigate multidomain interventions including in nutrition, medication optimisation and physical, cognitive and social activity. Some studies already show benefit, but data is scarce on the long-term success of programs.

“Social contact in any form has a potentially beneficial effect on dementia risk by building cognitive reserve, promoting healthy behaviours, and reducing stress and inflammation,” the authors write.

“Overall, even interventions with modest effects could theoretically have substantial preventive effects at the population level, including for people who are less affluent or in low-income settings. Interventions for individual and multiple risks would potentially be cost-effective but scalability is challenging, and interventions might need to be repeated at intervals to achieve sustained benefits.”

Related

Reduce smoking

Smokers have an increased risk across the lifespan, but midlife smoking confers the highest risk with some studies showing three times the risk for midlife male smokers and nearly twice the risk for midlife female smokers compared with non-smokers. Ex-smokers have no increased risk.

Control hypertension, especially in mid-life

It is recommended to keep systolic blood pressure down to 130mmHg from the age of 40. Midlife hypertension increases the risk for all-cause dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia, with mixed evidence about whether it continued to do so in older age.

“Although there is a scarcity of direct comparisons of the effect of different antihypertensives, a network analysis and systematic review identified that treatments with angiotensin 2 receptor blockers and calcium channel blockers (CCBs) were associated with lower dementia risk than other antihypertensives,” the authors write.

Treat high cholesterol from midlife

Every mmol/L increase in LDL cholesterol comes with an 8% increase in risk of all-cause dementia, evidence shows. A cholesterol reading higher than 3mmol/L increases risk by 33%, with the highest risk in people under 65 for a dementia diagnosis within 10 years.

Policy measures should be used to reduce sugar and salt content in foods sold, the paper says.

People taking lipid-lowering medication have no increased risk, while individual counselling and diet advice have “a small effect” in reducing LDL.

Prevent and treat obesity as early as possible

Midlife obesity is associated with a 30% higher risk of subsequent all-cause dementia than for those without obesity, and people with a larger waist circumference, especially over-65s, have a 10% higher risk of cognitive impairment and dementia than people with smaller waists.

Intentional weight loss of just 2kg is associated with improved cognition at six-month follow-up, with benefits more pronounced in people who lost weight through diet and exercise than through surgery. This suggests health behaviour has an impact on dementia, the authors say.

“Additionally, stigma in people with high BMI is associated with increased cortisol concentrations, inflammation, and negative health consequences, which might in turn contribute to the association with dementia,” they write.

Controlling obesity also mitigates the known risk factor of diabetes. This link is probably vascular, with insulin resistance also increasing amyloid β toxicity, tau hyperphosphorylation, oxidative stress and neuroinflammation.

Poorly controlled diabetes and long illness increase dementia risk, but “[n]ew evidence suggests that age of onset makes a difference”.

In people aged 70 and under, the risk increases by 24% for every five-year decrease in age of type 2 diabetes onset.

Results are mixed for the effect of diabetes medications on dementia risk. Some studies show that SGLT2 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors reduce risk but sulfonylureas increase it. Metformin studies show both no effect and significant reductions.

“Overall improved control of diabetes, but not very low blood sugar or weight loss without improved diabetic control, might attenuate the risk of dementia and be a way of decreasing dementia risk,” the authors conclude.

Reduce alcohol use

Drinking more than 21 units of alcohol per week in midlife is associated with a 22% higher risk of dementia than drinking under that amount, and also reduces grey matter.

Studies have found that occasional, light-to-moderate and moderate-to-heavy drinking all have less risk of dementia than heavy drinking, and there is a link between drinking and earlier onset of Alzheimer’s disease.

Reduce air pollution exposure

There have been nine systematic reviews since 2019 involving very large cohorts further demonstrating that particulate matter air pollution increases risk of dementia and cognitive impairment, and lessening air pollution lowers the risk.

Indoor pollution includes the use of solid fuels, in wood or coal burning stoves. “Residential wood- and coal-burning stoves are a source of indoor air pollution, and are reported to contribute 38% of the UK’s PM2·5 emissions and associated health risks,” the authors write.

The report also recommends evidence-supported interventions to help people live well with dementia once diagnosed. These include:

- Treating neuropsychiatric symptoms with care-coordinated multicomponent psychosocial interventions including stimulating activities. (There is no evidence that exercise alleviates these symptoms.)

- Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for people with Alzheimer’s disease and Lewy body dementia. “These drugs are cheap, with relatively few side effects; attenuate cognitive deterioration to a modest extent, with good evidence of a long-term effect; and are available in most high-income countries.”

- Caution over amyloid-β-targeting antibodies. Some trials show “modest efficacy” in terms of reducing deterioration – 27–35% after 18 months, but they’ve only been trialled in people with mild disease and few other illnesses, they have notable side effects and they’re expensive, the authors warn. They recommend full disclosure about lack of data and careful monitoring of patients.

- Caution over cerebrospinal fluid or blood biomarkers for people already diagnosed with dementia or cognitive impairment to exclude Alzheimer’s disease. Amyloid β biomarkers are common even in older individuals who mostly don’t go on to develop dementia. These tests also have limited generalisability outside White populations, the authors say. “The vision of blood biomarkers, such as phosphorylated tau, as a scalable test to predict who will develop dementia is progressing but is not yet realised.”

- Protect physical health, ensuring people are eating and drinking, as cognitive deterioration occurs faster for those admitted to hospital.

The commission considered other potential modifiable risk factors, including insufficient sleep, an unhealthy diet, infections and mental health conditions, but concluded that a high enough level of evidence does not yet exist. Stay tuned.