Expectation creep, protecting patient data from government and caring for outlier patients are a few things to worry about.

Last month I attended the WONCA conference in Ireland, where AI featured heavily.

I’ve been thinking a lot about it since and the impact it is likely to have on my practice.

There are several ways in which AI is likely to change my world.

Administrative load

The first is the most obvious: the administrative advantage of using AI to take notes in my consultations. While I recognise that AI is like having a student take notes, with all the omissions and potential errors, it at least gives me a working draft.

I think I’m going to respond to this initiative by including an edited form of the AI summary, including a title saying it is from an AI transcript. However, I then want to write a formulation paragraph at the end, to capture my thoughts about what really happened in the consultation. Like a diagnosis and formulation in psychiatry.

I suspect AI note-taking will come at a cost to the profession. I have learned to be suspicious about anything that claims to “reduce the load of GPs”. It usually means delegating work no one else wants, to me. Remember when computers were supposed to reduce our paperwork by creating paperless general practices? How did that go?

My daughter is a historian, and tells me every time someone invented a domestic labour-saving device we increased our expectations of what constitutes good enough housework. When we had card files in general practice, note taking was cursory. Now we have better notes, true, but our administrative load is metastasising as we expect our notes to perform a multitude of functions, including audit. AI will be another step up.

Data and compliance

I think it’s a short step from using AI as a tool to enabling governments to mine transcripts for data. The logical next step is to use it for further nudging. Or PSR action. GP data is just too attractive for governments to ignore.

During TMR’s Burning GP conference, Adjunct Professor Karen Price and I performed what we thought was a typical consultation to get the mixed audience to decide how much was “mental” and how much was “physical”. The point was to engage them in the Medicare nonsense of charging a consultation item number AND a mental health item number (23 + 2713). We used a case of a woman several months postpartum with ongoing vaginal issues after a complex delivery, including the psychosocial challenges of sexual dysfunction, relationship stress and lack of knowledge and understanding of the impact of breastfeeding on vaginal dryness.

After the play, I was astonished that a very senior person leading a digital health record strategy came up afterwards and said “That consultation was REALLY sensitive – privacy is a challenge isn’t it?” I think the data geeks forget how sensitive our data is. And I am not reassured by the multiple data breaches of recent times. As an individual, my data is not that attractive. If my data is in a large health database, it becomes highly desirable.

I am very worried about mental health specifically, because I have never seen a government content with less data than they had in the past. If Medicare decides to axe the mental health item numbers, there will be no way of tracking mental health activity in general practice. Counting mental health item numbers was never a good surrogate for mental health activity, but the risk is that without the 2713, it will look like we do no mental health work at all. They will continue to count treatment plans, but doesn’t that support the view that we are merely “glorifed referrers”?

The alternative, of course, is to use a lucrative AI tool which will, of course, benefit the tech entrepreneurs. We can mine the transcripts, they will say to governments, and have an easily managed way of seeing if GP diagnosis and management are “up to scratch” in mental health. That should be an easy win, and reduce low-value care, don’t you think?

I shudder to consider what that would mean with our most complex and vulnerable patients. Will those people avoid us altogether to maintain their privacy? And how will we manage the tech entrepreneurs with their aggressive marketing, and desire to co-opt physicians to champion their products?

When clinician entrepreneurs sit on our highest level of policy generation, and generate statements that “encourage” GPs to place digital health “at the centre of their care”, aren’t they behaving exactly like the drug companies who championed oxycontin in the 1990s?

Policy

I do think there is potential to use AI to map policy. This may not seem important, but it is. Imagine being able to ask AI to map the shortest way to secure care for a patient with an unusual constellation of disorders. Or to draft a practice policy. Or to detect the gaps or contradictions in a policy framework. This is difficult work, and I find it mind numbingly challenging. But AI can construct a flowchart. The next step is to examine that flowchart and determine whether the written policy matches “the way we do things around here” and deal with the gap.

Diagnosis

Diagnostic complexity is also a possibility for AI but could be a double-edged sword.

Remember that AI is based on what is available in the academic literature, where the researchers, subjects, grant leads, editors and guideline writers are all more likely to be white men from privileged countries and contexts. Even the standard research rat is white and male.

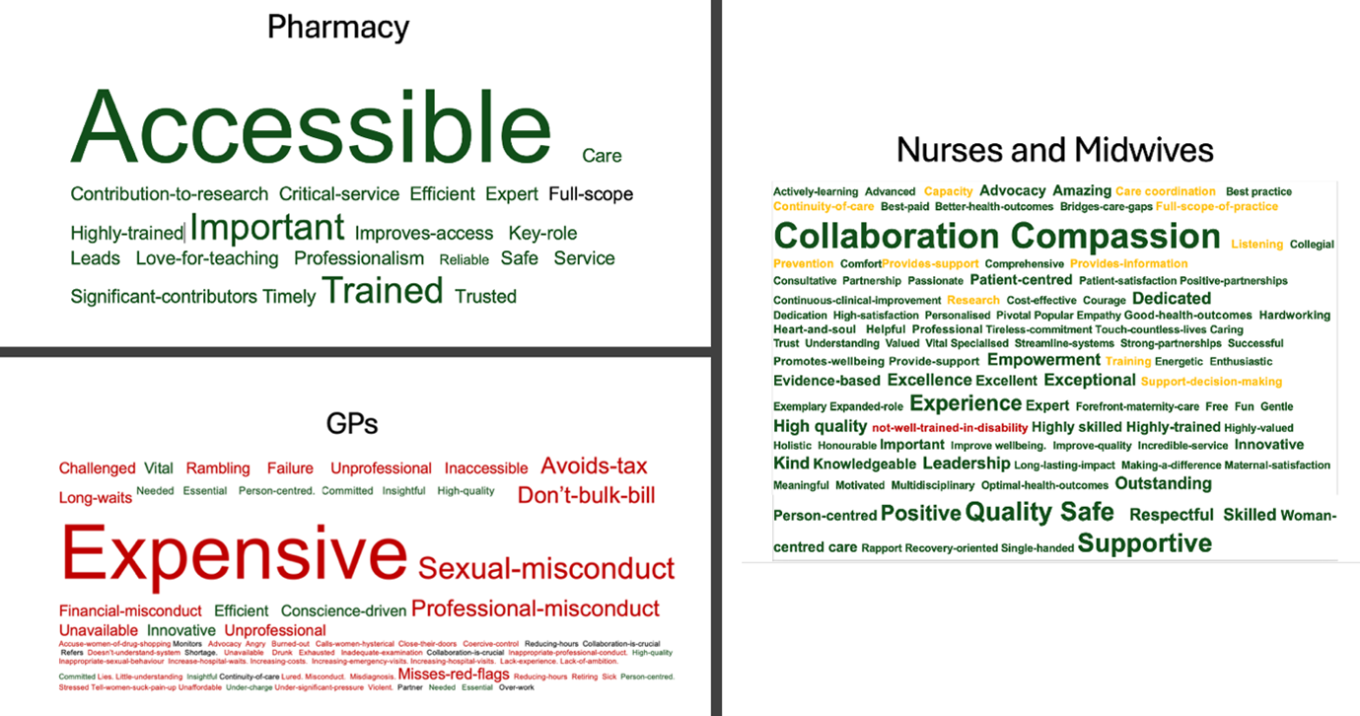

In this context, AI is likely to increase inequity by providing appropriate care for the average, and overlooking the outlier. I can see pharmacy and nursing, two professions with excellent skills in complex management, using these tools for diagnosis, and, in my opinion, that is a disaster for outliers. The problem is that politically, the greatest number of people will be absolutely fine.

The ethical question is whether the people on the margins matter. It may “waste” the doctor’s time seeing all the kids with a cold, but if you send all the kids with a “cold” to a less experienced diagnostician, the one kid with meningitis may well be missed. Do they matter enough to give everyone a more experienced diagnostician?

Related

Big qualitative data

I’m finding that synthesising qualitative data is a powerful communication tool. By synthesising, I don’t mean adding quotes, I mean analysing huge blocks of text and extracting word use.

I’ve published this before, but analysing 430,000 words of text generated by ACT Health (websites, reports, communications, Hansards etc) allowed me to extract the words used to describe the professions. It was painful, tedious, exhausting work that took weeks. But it enabled me to demonstrate bias very fast, and with minimal opportunity for the minister to refute the prejudice that has been obvious to GPs for years. AI will make implicit bias easier to find, I think.

So watch this space, and hopefully we will be able to do what we have always done and resist the temptation to overemphasise shiny new innovations in our care.

After all, we have always known that slow, complex, relational general practice has impressive outcomes for low cost. And I suspect we have the least inequity in the whole health system.

Associate Professor Louise Stone is a working GP who researches the social foundations of medicine in the ANU Medical School. She tweets @GPswampwarrior.