We increasingly rely on international graduates to fill the GP workforce, but many feel isolated and unsupported. The RACGP exam fiasco was the last thing they needed.

Fiona* woke up to a quiet house, got dressed, had breakfast and turned on her computer.

Usually, she would be able to hear her two young children padding around the house, but she’d paid handsomely to make sure no desperate cry of “mummy” this weekend could throw out her concentration.

So, with her family safely tucked away in a local hotel, Fiona was finally feeling confident to face two of her GP fellowship exams.

Her family had made countless sacrifices to get her to this day: 9 October, 2020.

A lot was riding on these exams. As an international medical graduate on a working visa, her bid for permanent residency hinged first on passing and then locking down an RACGP fellowship.

Worried about the spread of COVID-19, the college had delayed the Key Feature Problem and Applied Knowledge Test exams earlier that year. This left Fiona spending every spare moment working extra hours at the surgery and studying for the new remote testing format.

But as she began her KFP exam that morning from her home, she realised something was not right.

Fiona was just one of more than 1000 GP trainees who tried to attempt their Key Feature Problem exam in October, only to find the website frozen after 40 minutes with nothing but silence filling those anxious moments, staring at her computer screen in disbelief.

Fiona sat for two hours, hoping the exam would resume and unsure if it would be appropriate to use her phone – strictly prohibited in the exam rules – to contact the RACGP.

Eventually, at the time her exam was scheduled to conclude, she saw a statement on the RACGP’s website that a technical outage had occurred, and that the exam start times had been pushed back.

The second announcement from the college, almost three hours later, revealed that the KFP had been cancelled.

Tired, angry and confused, Fiona was only more disappointed to read on the RACGP website later that evening that the AKT scheduled for the following morning was also cancelled.

In the days and weeks following, the College board held emergency meetings to arrange a full refund of candidates’ exam fees and schedule a new paper-based exam, which would take place in early December.

It would not promise to pay for any other costs GPs in training might have incurred in preparing for the exams.

This left candidates on the hook for childcare, unpaid leave, hotel accommodation, travel and parking. For some, these bills were due not only for the original exam date in October but also for the re-sit in December.

Despite this setback, some candidates were happy to re-sit the exams at the end of 2020 and put an end to this exhausting and disappointing chapter of their fellowship.

But another group of doctors were furious with the RACGP’s pleas to “move on” from the blunder.

The last straw for IMGs

International medical graduates who contacted TMR said the exam debacle only exacerbated what felt like years of mistreatment in general practice.

Despite often being lumped together as one group, IMGs come from a diverse range of cultures and languages.

In the eyes of the Department of Health, an IMG is anyone who received their medical degree outside of Australia or New Zealand or completed their degree in Australia or New Zealand as a temporary resident.

Some IMGs have spent most or all of their careers as Australian citizens.

But for those seeking permanent residency, which is tied to them passing their fellowship exams, the bungle has added an intolerable amount of pressure to an already difficult situation.

“I’ve actually worked in Australia from my second year out of university, but I’m still classified as an IMG, and I will forever be an IMG,” says Carly*, a doctor who is currently on an independent pathway to RACGP fellowship.

Now this latest botched exam has reminded Carly of other experiences of discrimination she has faced as a woman of colour practising medicine in Australia.

In her experience, employers exploit the vulnerable position IMGs are in, recognising many are too scared to speak up for their rights, she tells TMR.

This is particularly the case when negotiating rostered hours.

“I’ve seen workplaces push IMGs around, and those practices who predominantly hire IMGs because of the reputation that we don’t raise our voices, and we do what we’re told,” she says.

“Just last week a colleague of mine, also an IMG, said that they had been rostered on every public holiday for the past year, but of course they are too scared to raise this concern with their employer.”

It’s perhaps unsurprising that bosses push the envelope, when the laws surrounding IMG work are so restrictive.

For example, there are already many hurdles to practising medicine as an IMG in Australia, including Medicare billing restrictions under the Health Insurance Act 1973.

Under this same legislation, IMGs are required to work in a Distribution Priority Area for a minimum of 10 years as a GP, or a District of Workforce Shortage as a non-GP specialist (known as the 10-year moratorium).

And as non-permanent residents, these doctors and their families are not eligible for any government assistance in the form of Medicare, public schooling or tertiary education – meaning all these expenses are paid for in full.

“IMGs are scared to speak up about mistreatment from a practice because their visa is literally in their employers’ hands,” says Carly.

Similarly, any negative reports from a supervisor could affect that individual’s temporary AHPRA registration and road to fellowship, Carly says.

Employers sometimes just lack understanding. At worst, they can be exploitative.

And if concern over her working visa and fellowship wasn’t enough, Carly has also experienced the challenges of taking maternity leave while trying to complete her general practice training.

Following the RACGP exam fiasco in October, Carly had to ask her employer for more leave ahead of the exam re-sit in December.

“He told me that I’d taken too much leave during my training,” says Carly. “The reality is that I’ve had two children in two years, and legally, that shouldn’t come up in a workplace conversation.”

Seen but not heard

The October exam meltdown wasn’t just a case of two missed days of work. It was in some ways an existential threat for some IMGs.

Doctors emigrating to Australia are granted provisional medical registration on the condition they are eligible to complete a specialist training pathway, or a pathway to enhance their existing specialist skills.

For IMGs on limited registration with AHPRA, they are given three years to complete all their fellowship exams, with an option to extend by two additional years.

For Nathan*, a doctor from Egypt on the independent pathway, the RACGP exam failure has put his immigration status in jeopardy.

“The RACGP has told us through this fiasco how important we (IMGs) are, and how much we are contributing to general practice in Australia, but our number one concern is that a lot of international medical graduates are on visas that are about to expire,” he says.

With his limited AHPRA registration only able to be extended by one more year, Nathan says if he finds out he failed the re-sit in December of last year, his life in Australia could be at an end.

The College has tried to be conciliatory, offering all candidates the opportunity to sit one KFP and one AKT at no cost over the next 18 months.

RACGP president Dr Karen Price says the college is moving to improve communication to all its members, and make sure everyone feels like a valued part of the GP community.

She says IMGs are the backbone of primary care, now making up more than half of the Australian general practice workforce and bring valuable skills to the role.

“Not only have they gone to rural and remote regions – and I know there was a moratorium that they had to – but more recently during COVID some IMGs used their language skills to help people in the community, who also spoke their language, understand the public health messages,” she says.

Recently, a move to transition non-vocationally registered doctors onto a fellowship pathway through the Practice Experience Program (PEP) has attempted to remedy issues raised by IMG doctors about the need for adequate support when emigrating to Australia.

Nevertheless, Dr Price acknowledges that while many international medical graduates are training on the AGPT pathway, those on independent pathways to fellowship are probably not as well supported with mentorship.

Dr Price says the moratorium presents another issue of isolation for IMGs, further exacerbated by existing rural workforce issues of doctors being reluctant to work in a certain location where they may feel unsupported.

And the fellowship exam delays happening amid a global pandemic, with doctors already under increased stress, doesn’t help.

“When you look at COVID, the water temperature in general practice has been at boiling point, and on top of that if you don’t have family in the country and you’re having to live and work hard, it’s a very stressful situation,” Dr Price says.

A biased exam?

The isolation faced by foreign doctors has long been thought to put them at risk of higher failure rates in the RACGP’s fellowship exams.

For the last decade, doctors completing an independent pathway to fellowship have been mainly left to prepare for the college exams with little external help, unlike the registrars completing training through Australian General Practice Training.

In early 2019 this changed, with support programs run by the RACGP and ACRRM finally offered to all non-vocationally registered GPs who were not in the AGPT program.

The RACGPdoes publish the pass rates for fellowship exams but does not break down the numbers for IMGs and domestic graduates.

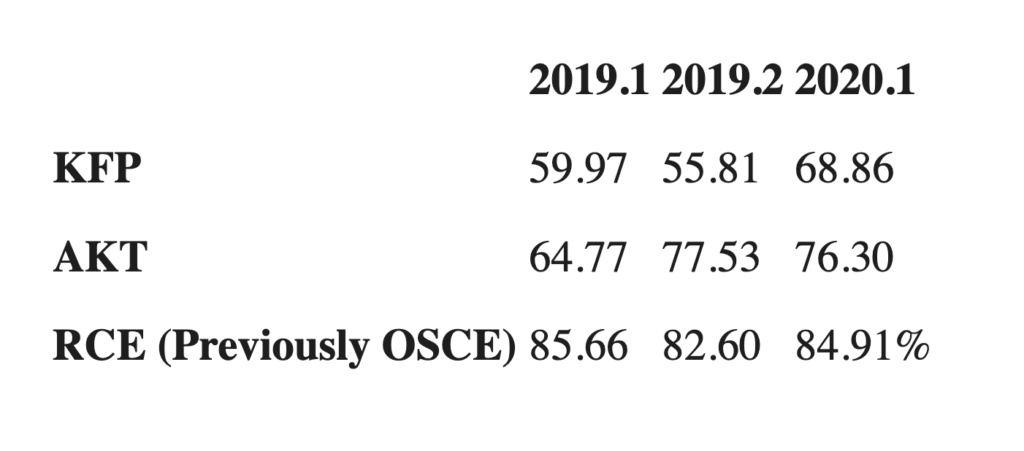

But the fellowship exam pass rates reveal that candidates struggle with passing the KFP exam, when compared to the higher pass rates seen when candidates attempt the AKT or Remote Clinical Exam (previously the Objective Structured Clinical Examination).

Pass rates of the RACGP fellowship exams:

Anecdotally, TMR was told that when attempting the KFP exam, more than 80% of IMGs fail at their first attempt.

TMR has also been contacted by a number of IMGs who are calling out the KFP exam for biasing the success of domestically trained doctors.

“It’s the people in the training programs that are getting through more easily with the KFP,” says Nathan. “Doctors on the independent pathway – which is predominantly IMGs – don’t get through.”

He notes that local students are taught as undergraduates how to succeed in these types of exams and have had additional training in the AGPT program in how to handle those questions.

“I think the testing system is flawed and that’s a big issue. And even more concerning is that we’ve known the statistics of IMG failure rates and just let it be, and there’s no real help provided.”

But Dr Tess van Duuren, RACGP acting censor-in-chief, says the RACGP acknowledges the KFP is a harder exam, mainly because it is not an assessment of knowledge recall.

“We do have a number of people who for various reasons are attempting this exam repeatedly. Unfortunately the more times you attempt and fail, the less likely you are to pass,” she says.

Some of that could come down to exam anxiety, says Dr van Duuren, but it could also come down to whether candidates are properly prepared.

“We know that the exams will drive the way that people prepare and when it comes to KFP, its main focus is on clinical decision-making as an output of clinical reasoning, which is a very important skill for any doctor, not just a general practitioner,” she says.

“The KFP is not just assessing that the candidate has the ability to know and recite knowledge but that they can demonstrate an ability to interpret information, place it within a defined clinical context with the patient that is sitting in front of them, and use that information to get the outcomes that they need for that patient.”

Dr van Duuren says while different colleges might use different styles of exams to assess their trainees’ clinical reasoning skills, there remains no standardised mode of assessment.

In addition, the RACGP says the exams are written and reviewed by a large pool of fellows who reflect the working demographics of general practice.

“These fellows (who write the exams) come from very many different backgrounds, countries, language groups and also pathways to fellowship,” says Dr van Duuren.

Unity, within diversity

Dr Hash Abdeen, chair of the AMA Council of Doctors in Training said that with IMGs in Australia being so diverse, it’s a significant challenge toencompass all the needs of this group of doctors.

“In terms of representation from an AMA perspective, we’re very keen to make sure that the AMA as an organisation reflects the profession and its diversity,” he says.

“With the AMA Council of Doctors in Training that goal includes increasing our representative roles in terms of IMG representation, so we can make sure that we’re trying to do better to advocate for these trainees.”

But Dr Abdeen said the GP training colleges also have a responsibility to all trainees to make sure everyone is receiving a training experience of equal quality.

“We also need to go one step above that and make sure it’s equitable training as well, because different trainees have different needs, whether that be someone from an IMG background, someone with a disability or someone with a mental health condition,” he says.

And it’s not only in the best interest of these individual doctors for colleges to pay attention to these issues now, but also because the future of general practice depends on IMGs being happy and highly skilled doctors in the future, Dr Abdeen says.

General Practice Registrars Association president Dr SamaBalasubramanian said one of the ways medical colleges could better support IMGs is to ensure they don’t ignore the experiences or feedback provided by trainees.

“The only way we can change the system for the better is to support these people and so when we do hear these things from IMGs, the question is now ‘What do stakeholders do with that information to ensure that problems are resolved and rectified?’ Because the last thing we want is people working where they don’t want to work, disempowered and disenfranchised,” he says.

For Dr Balasubramanian, who migrated from India to Australia in the early 90s as the child of an overseas-trained doctor, IMGs’ negative experiences hit him personally.

“For me it’s a real tragedy how many of our IMG colleagues feel forgotten, especially considering the good work that they do, and the fact they certainly deserve better from the system that they’re in,” he says.

“The only way that’s going to change is if we can appropriately tell this story, represent international medical graduates appropriately, and let them be actively involved in changing the system.”

*Names have been changed.