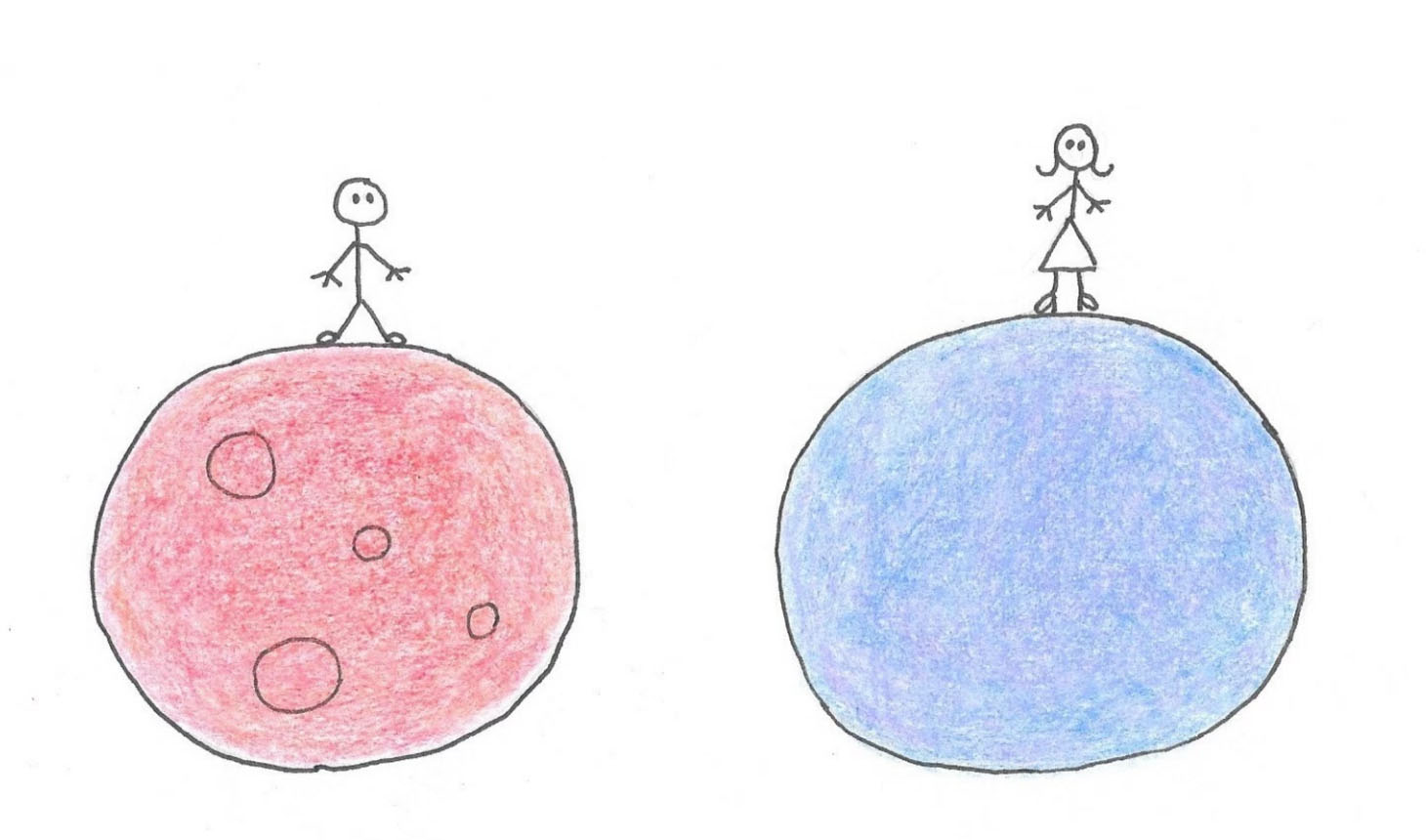

Men think no one shops for health care. Women think everyone does. How does that affect healthcare reform?

although they don’t control the money, 90% of Healthcare decisions are either made or significantly influenced by women. Ex New York Times journo and now healthcare cost comparison start-up founder Jeanne Pinder ponders what that might mean for the future of healthcare reform

Men and women think very differently about health care costs. When I talk about the topic, it’s common for me to see half of my listeners zoning out — the male half. Why? Well, because women make or influence 90 percent of health care decisions, according to a study by the American Academy of Family Physicians. Of course, men go to the doctor. But they make fewer health care decisions, and they don’t think about pricing the same way women do.

Women are more in touch with health care pricing and more affected by it than men. Women own reproductive health. Women make pediatricians’ appointments and run elder care. Women nag their spouses, be those spouses husbands or wives or none of the above, to get their cholesterol checked, to pick up a prescription, to go to that physical therapy appointment.

So when we talk about shopping for health care, about our business, we’ve grown accustomed to having dudes say “Hm, interesting, can we talk about wearable devices?” or “We have some big data, we’re not really interested in the prices.” At the same time, women tell us how excited they are that we’re attacking opacity in health care pricing.

Now don’t get me wrong: I like men. A lot. But by and large, they don’t get this issue.Women see the doctor more than men do. Women make 4.6 doctors visits a year, three times more than men do and twice as many as their children, according to a study by the Centers for Disease Control. And women have a lot of purchasing power generally, as marketers know. Fleishman Hillard Inc. estimates that women will control two-thirds of the consumer wealth in the U.S. over the next 10 years,” Inside Radio reports about women and their purchasing power.

The coffee shop test: A telling example

Beyond the studies, here’s one from my personal experience: When we took the embryonic version of our software to a local coffee shop to test it with real people, we had a telling series of reactions.

We took three sample “explanation of benefit” forms with real reports to a Starbucks, with a handful of Starbucks gift cards and set up a sign saying “Earn a $10 gift card testing our software.” The task was simple: use the benefits forms, put information into our PriceCheck tool, and help us learn how to make it better.

Six men and five women volunteered. The six men, to a man, looked at the explanation of benefits and complained bitterly about it — then told her her software didn’t work.

The five women? They wrestled through the E.O.B. (yes, they’re confusing, but they can be deciphered) and input their data. Then they said, to a woman, some variation of this: “I’m so glad you are doing this — it’s really important. Let me tell you what happened to [me, my mom, my daughter, my sister, my girlfriend] with a health care bill. Thank you for what you’re doing!”

Here’s another story from my personal experience. I was talking to married friends — he’s a Manhattan specialist doctor and she does many things, including taking charge of the kids’ medical events. She told of how one child needed a sleep study, so they were given equipment for an in-home test — to take home, hook up the child overnight, and then send data back to the doctor. As she described the $3,000 sleep study bill, and her fight to get it reduced to $200, he listened with amazement. This was her issue, her job — not his.

Another story: I run a start up called Clear Health Costs. In general, I don’t spend a lot of time talking to wealthy venture capitalists (who are predominantly male) about this topic. I learned early on that I would spend a lot of time explaining the idea of an opaque marketplace and vast pricing disparities, generally to a lot of questions. But one V.C. asked to meet by phone and so I agreed. His motive? He had just switched his firm from a standard insurance plan with a low deductible and low co-pay to one with a high deductible. He took his daughter to the local Pediatric Clinic, and got a $260-plus bill for a 15-minute visit, and wanted to tell me about it.

No, he didn’t want to invest — he was just surprised, and wanted to tell me. (Sigh.)

By and large, it’s women

Women earn less than men: an average of 79 cents for every dollar men make. So high health costs have a disproportionate effect on women: that $1,000 medical bill for a woman is a $790 medical bill for a man. Two-thirds of minimum wage workers are women. (Related: Lower wages combined with higher health costs, as well as child care, mean that that women lose multiple opportunities to save for college, plan for retirement, buy a better car, move into a better home.)

In single-parent families, health care costs are a constant threat to economic stability. This is true not just for the poor and uninsured, but also for the middle class and the working poor.

Women run more single-parent households. 40 percent of working mothers with children under 18 are their families’ sole or primary breadwinners, and 83 percent of single parent families are headed by women.

The gender lens

We could argue about my next statement, but experts in marketing will tell you that gender makes for a huge blind spot. “Gender is the most powerful determinant of how we see the world and everything in it,” writes Forbes contributor Bridget Brennan. “It’s more significant than age, income, ethnicity, or geography. Gender is often a blind spot for businesses, partially because the subject is not typically addressed in most undergraduate or graduate-level business courses, or the workplace itself.”

Of course, many men get this issue of rising health costs. But they’re the exception, rather than the rule.

To be sure, many women don’t care much either: If they’re healthy, or have great insurance, or wealthy enough not to care — or for whom the problem is an abstraction. And then things change.

And of course, there’s this video, which never fails to worry me.

What does this mean for us, when we talk about shopping for health care? If I’m talking to a woman, she’s often informed and excited. If I’m talking to a man, I often need to explain the entire landscape, and detail who’s shopping for health care, how the marketplace works, and so on. By the time I’m done explaining the givens, our time is up and he doesn’t get it.

So what does this all add up to?

We have a wide gender disparity in people’s perceptions of our key problem.

Jeanne Pinder served as an editor and reporter and human resources executive at The New York Times for 23 years before leaving to found Clear Health Costs, a startup based in New York City. This is an edited version of a blog that appeared on the Clear Health Costs blog HERE