How do you abide by an unintelligible law? Here are a few items that no one knows how to bill correctly – including the Medicare folks.

There is a common view that medical billing is easy, that anyone can do it and doctors can learn what they need to know on the job – apparently, it’s a cinch!

A university dean once tweeted that outsourcing medical billing was like outsourcing hospital laundry services – so, basically donkey work.

Odd, then, that the justice system takes it so seriously.

Judge:

This may seem a silly question, and I apologise if you have already answered it, but I am still unclear about one thing. How do doctors know which fees to apply?

Witness for the prosecution:

That’s actually a very good question your Honour. Doctors will usually just do what everybody else does. So, basically what they have heard, or what someone has told them – could be a colleague, a practice manager, secretary – anyone really.

This is not a screenplay but a real exchange between me and the judge earlier this year when I was summonsed to appear as a witness for the prosecution in a criminal trial concerning alleged medical billing fraud by a doctor.

After more than six hours over two days in the witness box, I suspect my evidence ended up being much more valuable to the defence than the prosecution. Why? Because the truth revealed that our medical billing system is a mess.

I knew the prosecutor had his work cut out. It is no mean feat to prove to the requisite criminal burden of proof (beyond a reasonable doubt) that a doctor acted with deliberate intent to defraud when relevant laws are so opaque and interpretive they could mean anything. My evidence alone would have sprayed the prosecution case with reasonable doubt holes. I’ve checked on AHPRA, and the doctor is still practising with no restrictions.

The bottom line is that if the government wishes to control the medical billing behaviour of doctors through law, then the law must conform to certain minimum standards to enable it to be obeyed. It currently does not.

Imagine how traffic would be affected if road rules said: stop at a red light not being a light that appears orange; give way to the right except when approaching from the left; indicate when turning a corner but only if you are over 75 or a concession card holder and attend up to a maximum of 10 corners during any single driving episode.

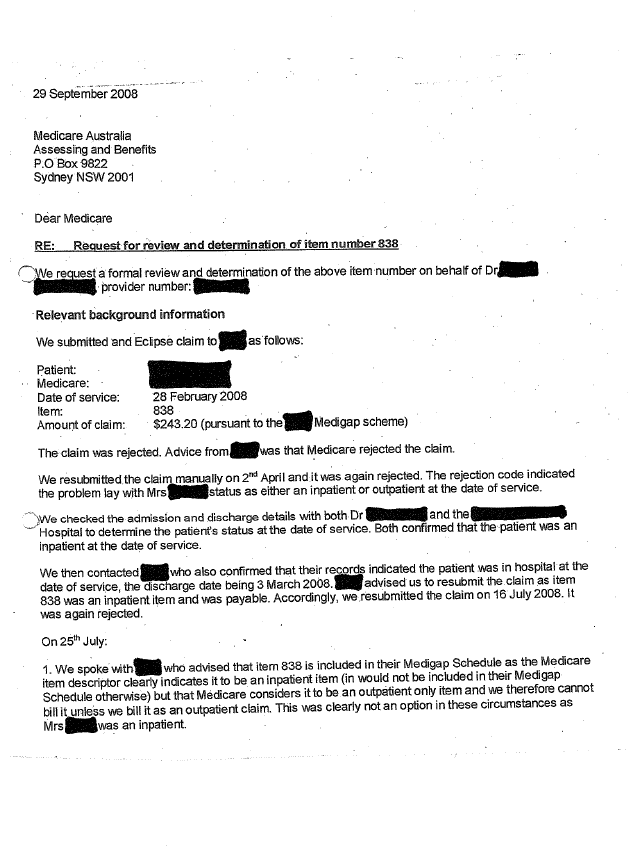

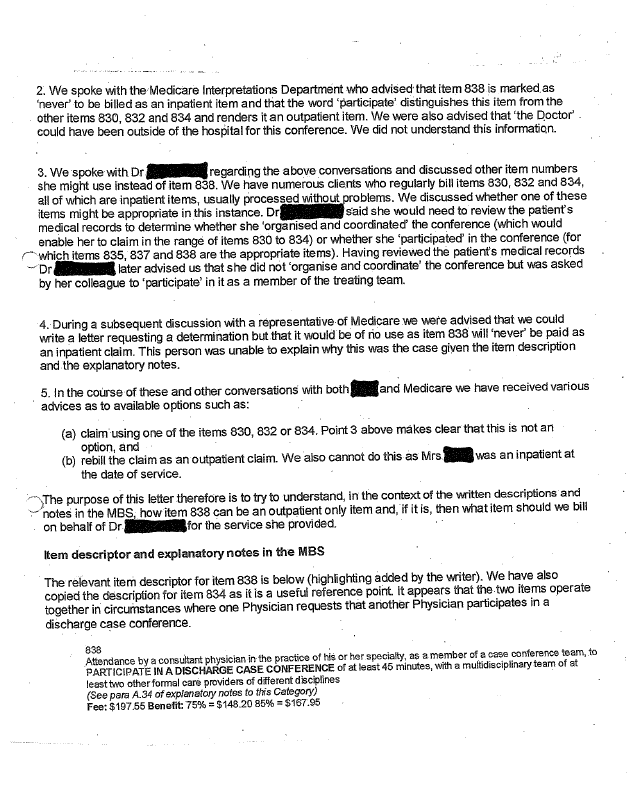

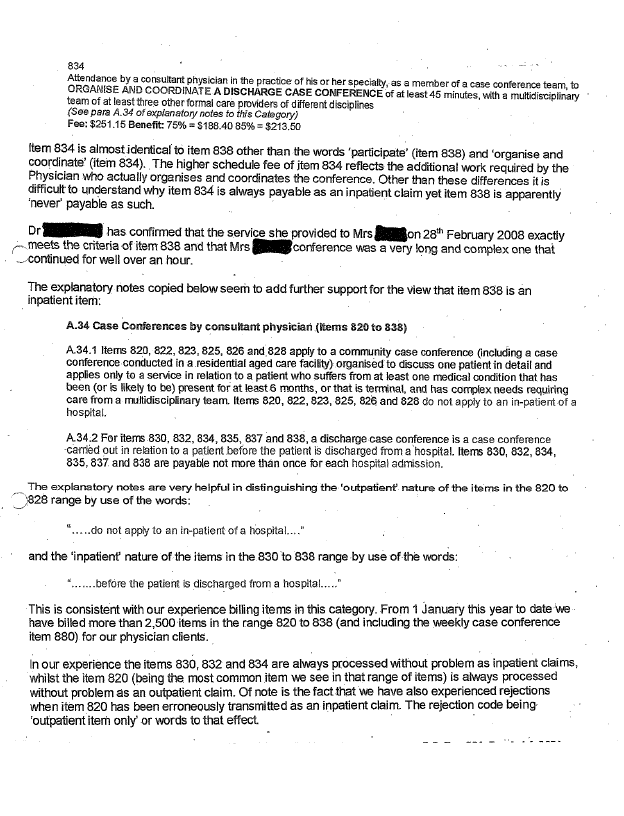

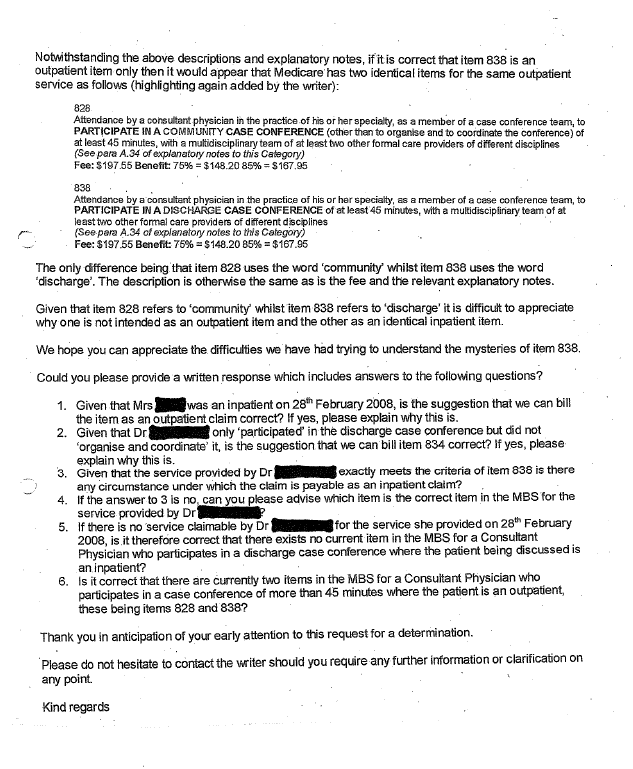

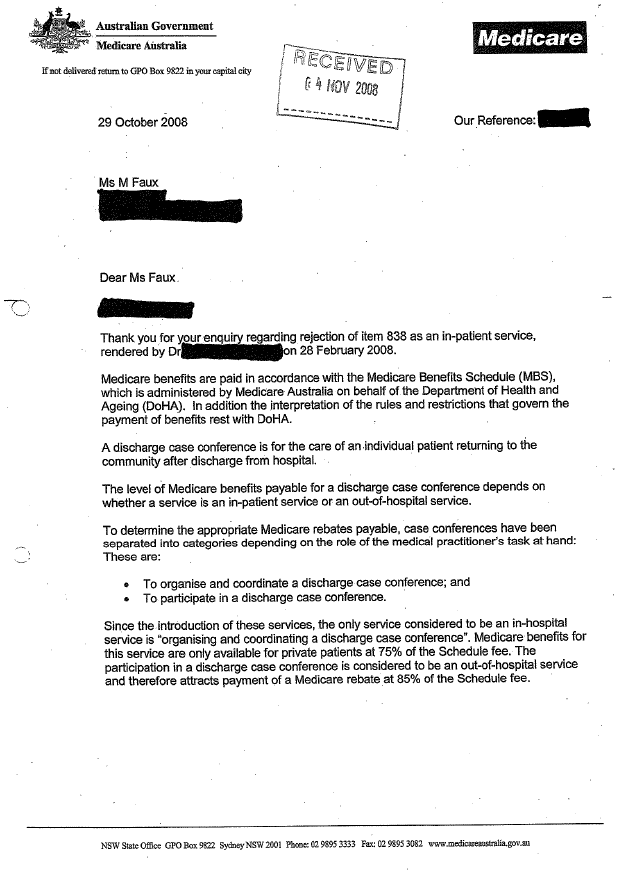

These analogous examples are unfortunately not exaggerations of the types of incomprehensible descriptions that litter Australia’s medical billing landscape. The appendix at the end of this article is a good example relating to item 838. Item 838 clearly states the service must be provided before the patient is discharged from hospital, but the convoluted correspondence concludes the item can only be claimed after the patient has been discharged. This has not changed since the date of the letters. There are many more examples.

Item 14245 is not clear about whether the doctor who claims the item has to remain in attendance for two hours during an infusion with a risk of anaphylaxis and given the anaphylactic risk, whether the patient should be admitted and treated as an inpatient, and how that is possible given an adverse reaction does not satisfy relevant private health insurance admission rules, and nor does the short two-hour infusion period.

Item 132 (complex initial physician attendance) is unclear as to whether the 45-minute requirement is for face-to-face consultation with the patient or whether it can comprise face-to-face and administrative time.

Items 4001 and 16500 (both antenatal care) should not be co-claimed, but this is not clearly stated anywhere, and on one not unreasonable interpretation the two items should always be co-claimed.

Item 21070 describes initiation of anaesthesia for intraoral procedures and item 22900 describes initiation of anaesthesia for extraction of teeth; both items obviously relate to the mouth but there is no clarity around which should be billed when, and an anaesthetist who regularly delivers anaesthetics for general oral procedures could easily make the mistake of billing item 21070, innocently assuming it would cover teeth.

Item 47981 is in the orthopaedic surgery section of the schedule even though it is an operation a general surgeon may provide, and it is unclear whether a general surgeon (rather than an orthopaedic surgeon) can claim it.

In the highly specialised area of radiation oncology, at least three reasonable interpretations of a common item number combination are possible for a cancer patient receiving radiation treatment to two separate anatomical sites (such as their hip and spine) on the same day. In that case, our client was concerned because the item combinations were being paid or rejected arbitrarily, meaning they had no way of knowing which was right or wrong. We telephoned the MBS provider advice line twice on the same day during that project, to discuss the correct approach. One representative said two of the items should always be co-claimed, the other said the opposite, and neither knew how to approach the fee calculations. They said it was complex! Well on that point at least, they were right.

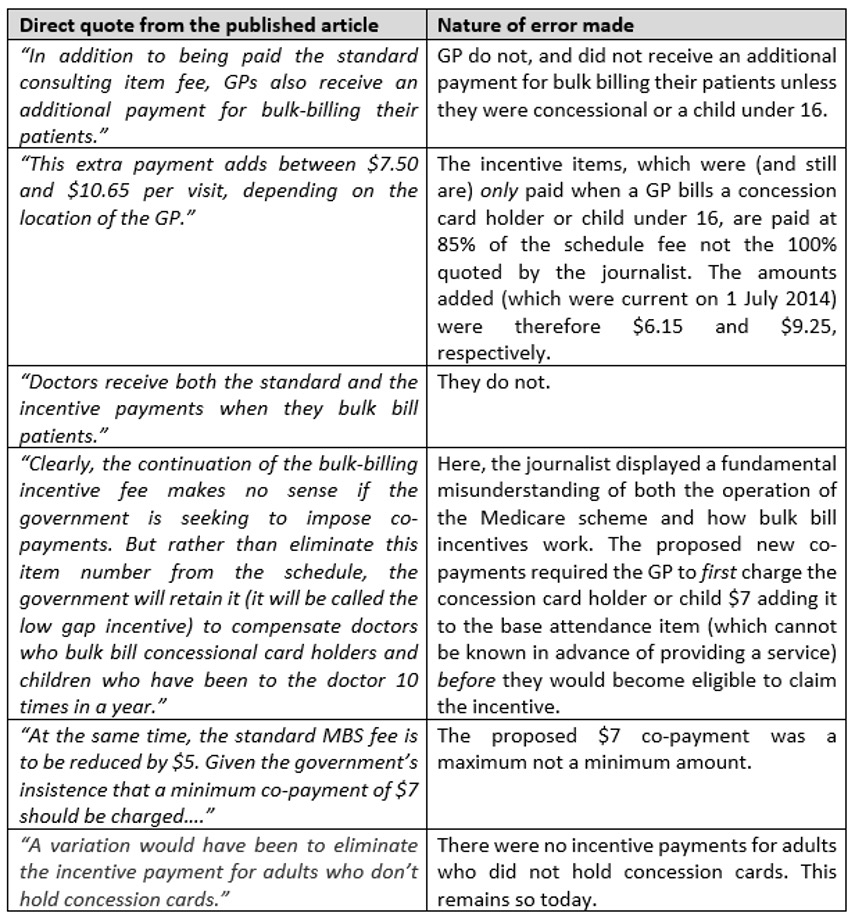

In addition to Medicare finding Medicare complex, well intentioned journalists also struggle. During the 2014 co-payment debate, a well-respected professor of economics, reporting in a leading Australian newspaper, was unable to understand how the bulk-billing incentive items and proposed changes would work. Here’s what was published, and the errors made.

Yet, while highly capable journalists may be forgiven for finding Medicare and medical billing difficult to understand, no such generosity is afforded doctors should they experience similar confusion.

And like the judge in the case earlier this year, other members of the Australian judiciary have also found medical billing anything but simple once it is dissected. In one case a judge forcefully stated that a not unreasonable interpretation of an item number should not render a doctor criminally liable. On that I think we can all agree.

Medical billing is neither easy, nor is it donkey work and doctors are not clairvoyants. My PhD has put these facts beyond dispute, with the evidence having been rigorously tested through peer review. We now know that Australian medical billing is a profoundly complex system of laws that doctors do not understand (no one does if truth be known), and administering it is one of the most important and responsible jobs in the entire health sector – spending taxpayers money with every click.

Reforming this mess must start with the law – to make it make sense – but at the same time we must facilitate harmonisation of our bedrock clinical terminology product (the MBS) with international standards on health data governance. If we wish to preserve Medicare there is no time to waste.

Margaret Faux is a health system administrator, lawyer and registered nurse with a PhD in Medicare compliance, and is the CEO of AIMAC, which offers courses and explainers on legally correct Medicare billing