The system is stacked against GPs, who do the vast bulk of mental health consults for a fraction of the money that other specialists are paid.

There is a much-quoted figure asserting that 30% of all healthcare is low value.

This figure is, of course, nonsense. It’s no more accurate than saying 30% of the population are unhappy, or 30% of political discourse is courageous.

I have no doubt that if we took a part of medicine where outcomes are quantifiable, like orthopaedics, we could identify that certain procedures are low value in certain circumstances. In my world as a GP with deep expertise in mental health, the situation is much less clear.

As a qualitative researcher, this tendency to think numbers provide some sort of accurate understanding of non-qualitative concepts is at best irritating and at worst manipulative. Using a graph to represent complex mental health outcomes makes no more sense than asserting that a flower is efficient, or a spreadsheet is insipid.

The tendency to try to turn medicine into a selected, quantifiable cluster of small mechanical parts is not new. But it used to be levelled at the medical profession. Ivan Illich wrote a scathing commentary on the qualitative experience of healing, and the way doctors privilege scientific analysis of disease over the experience of illness: “Medicine tells us as much about the meaningful performance of healing, suffering, and dying,” he wrote, “as chemical analysis tells us about the aesthetic value of pottery.”

Now, it’s the economists, data entrepreneurs and policy makers thinking that biochemical analysis of a single species will give them a perfectly valid understanding of the entire Amazon.

Value in healthcare is measured by dividing the outcomes that matter to patients by the cost of care. Let’s look at what we know about both in general practice and specifically in GP mental health care.

GPs provide good outcomes

There has been a lot of rhetoric around patient-centred outcomes applied to general practice from other settings. The ideal place to implement outcome measures is where there is a definable disease or condition (e.g. cataracts) with a measurable impact on the patient (reduced vision) and then a distinct intervention at a moment in time (lens replacement) with a measurable outcome (improved vision).

It shouldn’t need stating, but mental health is not like that.

The fact that mental health is not, in essence, a quantitative experience hasn’t stopped many services weaponising numbers to drive government investment. I’m sure healthcare economists would be a lot happier if we all stuck to the formula that cataracts manage so effortlessly. In mental health, it is easy to produce outcome data. It’s just not easy to make it valid.

There has been extraordinary investment in the glitter of data. Whether it produces value is a different question. When do I measure “outcomes” in a patient who lives with fluctuating mental health over decades? What “data” is valid? Is my understanding of “worthlessness” on an outcome tool the same as yours? Is the tick box outcome tool I use “real” the way an X-ray is “real” or is it a tool to help a patient communicate with me? If a patient knows a score on a tool or an interview influences their access to care, will they make sure they meet the cutoff? I would, and so would everyone else, if they knew. The people who know, of course, are more likely to be privileged, which has an equity impact, but that’s another story.

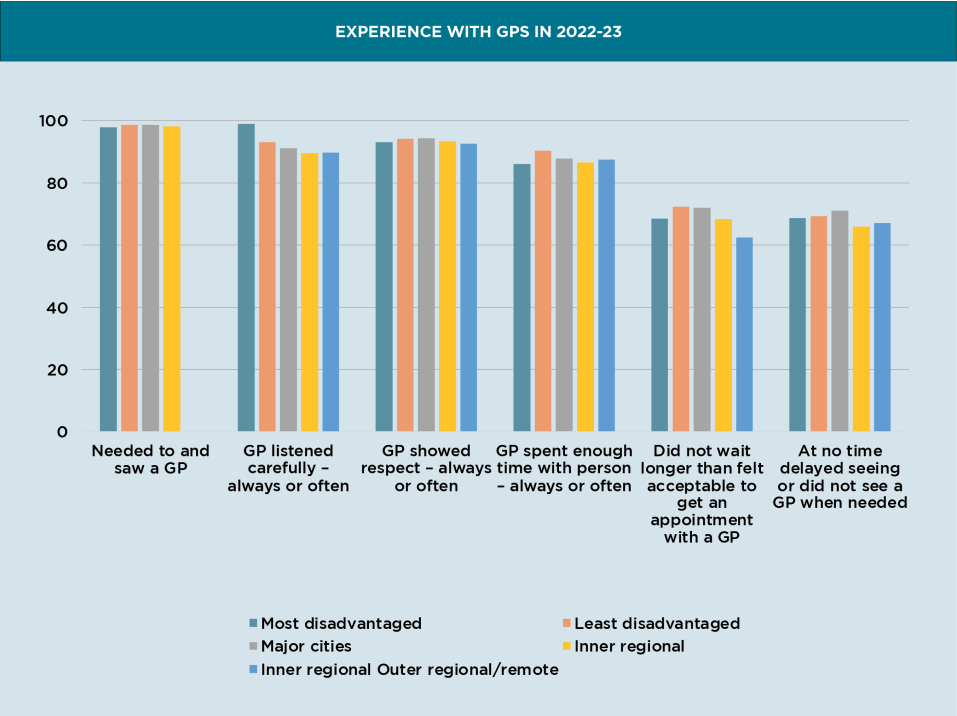

When we look at outcomes, we need to start with a benchmark of current care. Are GPs providing anything useful? We know they keep patients alive for longer and improve the health of communities. I can talk all day about the data proving the worth of generalist care or the data that shows that the impact of empathy or the quality of the therapeutic relationship is greater than any evidence-based technique, but overall, we have Australian evidence that GPs are pretty good at what they do. We can’t break it down to individual interventions, but I would argue that this is not the point.

GPs provide care that patients value, and they provide that care across socioeconomic strata and geographic contexts. GPs are providing services to patients in a timely way and they choose to spend time with patients, even though there is a profound cost when they do so. Patients are satisfied (or they were).

Mental health services, on the other hand, are highly inequitable with the poorest fifth of the country having three times as much mental illness and only a third of the access to services.

Cost

The other side of the value equation is cost. How much does it cost the community when GPs do mental health care? Should we be rationalising this and nudging patients towards cheaper care?

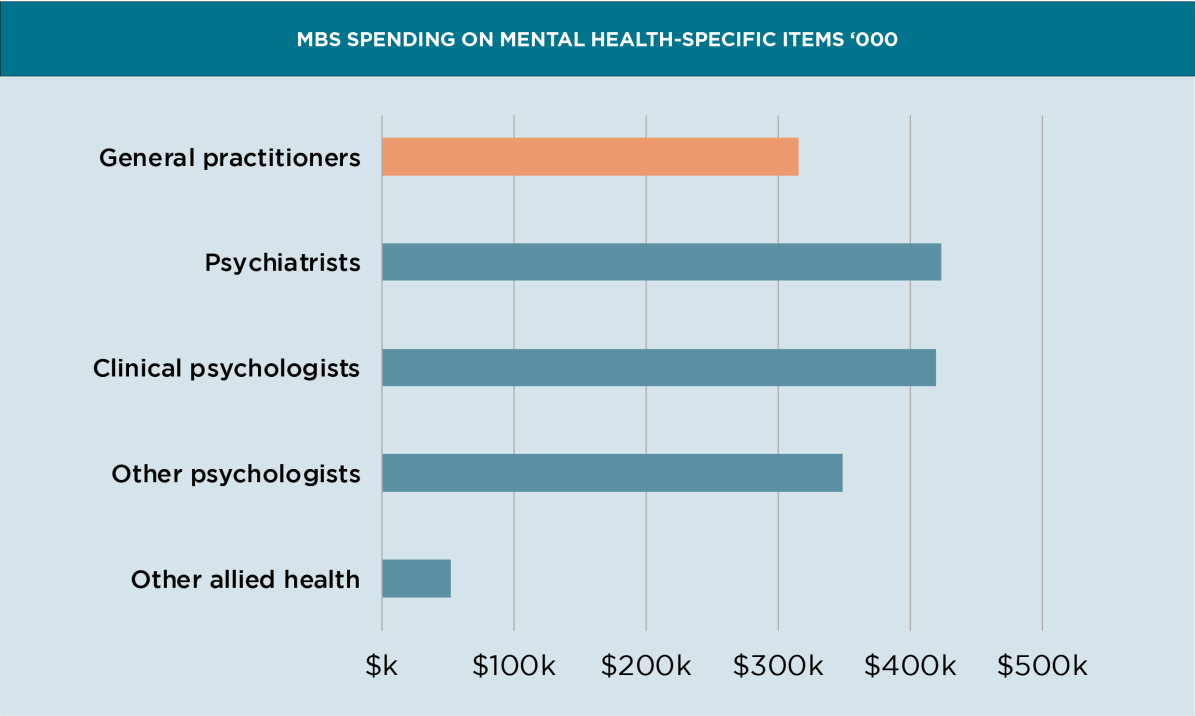

The short answer is no. This graph shows the total Medicare spending, with GP mental health item numbers highlighted in the grey sliver. Of course, we could argue that most GP mental health care is not provided using mental health item numbers, but let’s not muddy the waters just yet.

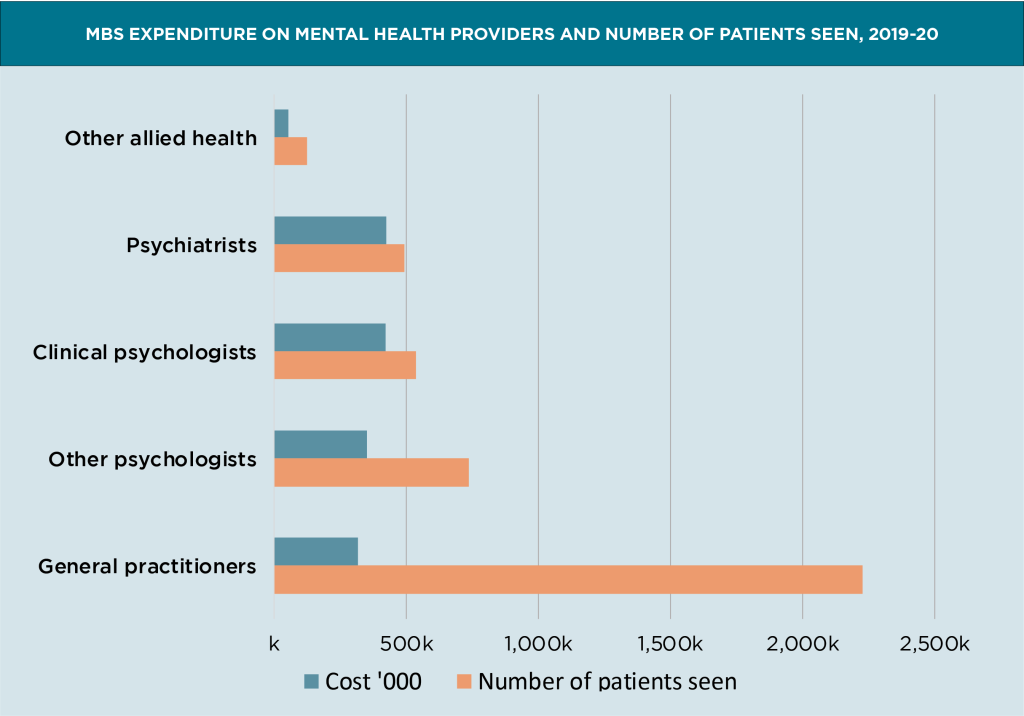

We see more patients than psychiatrists, psychologists and other allied health professionals combined while receiving less than a quarter of the money.

It is even more obvious if you count what we do, rather than using the default metric, which is counting the mental health items we bill. This graph shows how ridiculously efficient we really are. Here, the orange bars show the number of patients who get care, and the blue bars show the cost. Conclusion? We are very, very cheap.

We also charge very little co-payment compared with any other mental health professional.

So, GPs provide, on average, a service that patients find accessible, affordable and satisfactory for a much lower cost than other services. GPs provide excellent value for money. We would expect, therefore, that any policy maker would try to use the levers available to them to encourage patients to see GPs for their mental health care, rather than use much more expensive services. Unfortunately, this is not what the policy levers are designed to do.

Low-value policy

There are several government policies that are impacting general practice mental health care. The economic drivers of Medicare were always towards shorter consultations. Before MyMedicare, an hour of my time doing 10-minute consultations attracted Medicare funding of $300. An hour with a patient with a mental health concern, or seeking antenatal care was $76.

MyMedicare increased the incentive payments for all consultations, EXCEPT for mental health and antenatal care.

There is now a widening financial discrepancy between those who are responding to the economic levers in the Medicare system and those who aren’t. The policy is screaming at me to cease my current practice immediately, and find a way to redirect complex patients elsewhere.

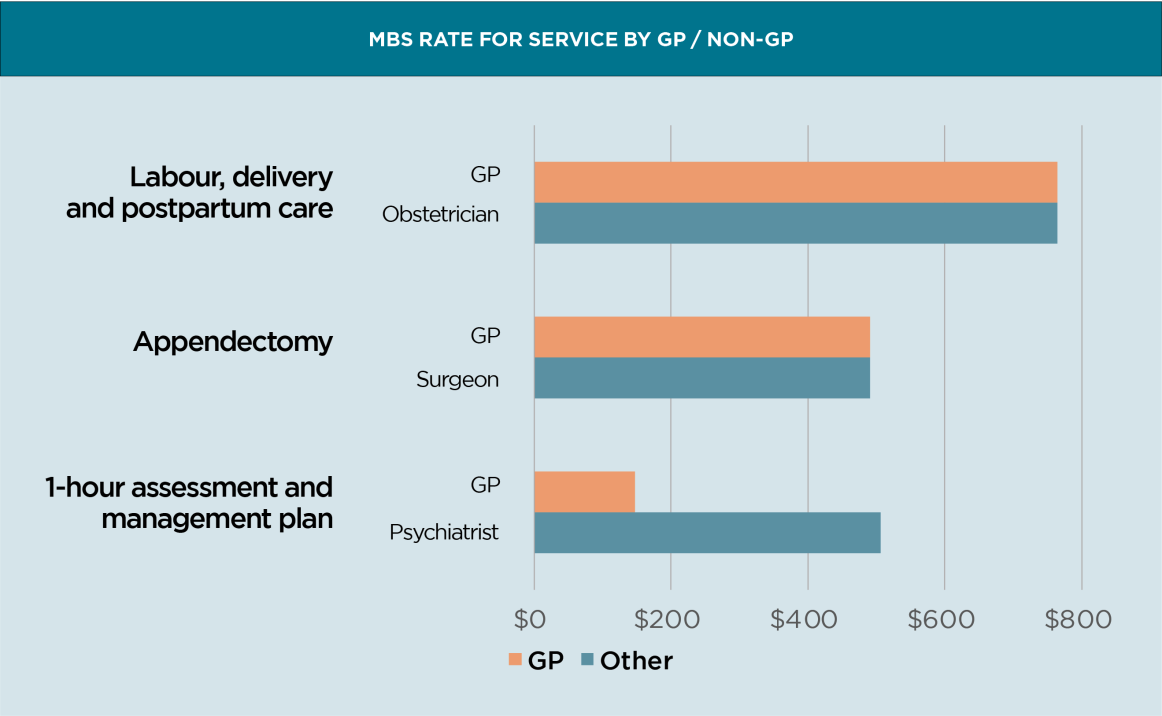

It’s not the only economic driver. Some time ago, we decided that equal pay for equal work might be a reasonable thing. A GP surgeon, anaesthetist or obstetrician earns the same as their non-GP specialist colleagues for doing the same job. This is not the same as a GP with expertise in psychiatry.

However, financial levers are only one set of nudges in a whole integrated set. I now need to do audits as part of my compulsory CPD, which is a whole lot easier if I see patients who generate numbers. No wonder it’s easier in a hospital where someone else in the team or the research unit can extract the data. The benefits to the government and the data entrepreneurs of GPs producing such nice, juicy data are not lost on me, and neither are the privacy risks to my vulnerable patients.

Governance drivers push me away from complex care too. AHPRA causes harm. Being named and shamed on the public register causes harm. The PSR telling me to have a good, hard think about billing long consultations causes fear. The nudge letters from the federal government cause fear AND harm. All of those regulatory levers impact workforce. GPs are leaving the profession.

And just to add to the gaslighting and crazy-making environment in which we practise, apparently being afraid of audit means we are “paranoid” – an old barb that still rankles.

Shame is a powerful motivator, particularly for doctors who tend to at least start out with the desire to do some good in their communities. When Mark Butler told the community they should “vote with their feet” and shop around for GP practices that bulk bill, he was suggesting that GPs take a good hard look at themselves and stop behaving badly. I think this is a bit like the upper classes in the early 20th century accusing their underpaid domestic servants of being uppity when they expected to be paid.

Every single policy lever I can think of drives GPs to bill less, choose simpler patients, practise defensive medicine and avoid anyone who could possibly misconstrue or complain about anything. In other words, I should stick to straightforward 10-minute interactions with an agenda and outcome I can defend. Preferably with patients for whom it is easy to collect data.

These are not the patients who have deep mental health concerns, difficult psychosocial circumstances or multimorbidities. We should avoid consultations where emotions run high, needs are deep, consultations are complex and resources (especially in mental health) are almost non-existent. These patients need us, but we cannot keep them safe because we can’t access the resources they need to survive. It hurts to watch them harmed by a dysfunctional system. The moral distress we have when we can’t do what we are trained to do burns us out. Do you blame any GP for wanting to walk away from this sort of repeated trauma?

Every systemic driver there is pushes me away from the job governments say they want me to do.

Related

Butler recently commented that the problem with attracting doctors was a cultural one within medicine. “We’ve got to get away from this idea that general practice, the backbone of our healthcare system, is somehow a B grade,” he said. So even when the government has used every lever it has to show the community how little general practice should be valued, it is surprised that junior doctors are not clamouring to become the next generation of scapegoats for a failing health system.

Holding policy makers accountable for value

To be clear, I have no problem with reducing low-value care. I have a problem with the validity of the metrics defining it in my discipline. General practice is highly complex, and I believe we are falling into the trap of using over-simplified models for complex biopsychosocial systems. Complexity theory is an ideal place where AI adds value, but it needs to be more than individual measurement of individual components of care to add value.

General practice is cheap, efficient and effective. We are investing an enormous amount of public money on the assumption that measuring it will make it more cheap, efficient and effective. The side effect is that we have a severe shortage of workforce because general practice has become financially and emotionally unsustainable. GPs are donating increasing amounts of time to meet the needs of low value bureaucracy. Our governments are diverting resources from clinical care to health economics, data infrastructure and policy analysis. The question is whether Australians are getting better healthcare for their investment.

As a community, we do a lot of things without evidence. Collecting evidence is an intervention and it has a cost as well as a potential benefit. Perhaps the best expression of this is from a doctor and health economist partnership:

“Should clinicians be allowed to be the final arbiters of low-value care? In making complex and highly individualised clinical decisions, nuanced clinical judgements of experienced, well-informed clinicians will arguably outperform any service-level measurement and incentive program aimed at recognising and reducing low-value care. Attempts to distil and apply evidence-informed ‘do not do’ rules at the population level are bedevilled by the rule of legitimate exceptions when care is directed at specific individuals.”

Pruning the Amazon

The Amazon is reaching a critical turning point, with deforestation threatening all of us. It is estimated that over a million species are yet to be identified, but they all contribute to the “lungs of the world”. The edges of the Amazon are now colonised by domestic animals preferred by people in power, and those who profit by the products. The people who were stewards of the land are losing their livelihood and communities and whole ecosystems are dying.

Primary care is an ecosystem that supports the rest of the healthcare world. We do not really understand how healthcare works, in all it’s complexity. We cannot identify all the interventions we provide, and the interdependencies they have. When we try to reshape general practice, by managing what we can see, we change the ecosystem. We are seeing the cost of that strategy in a dying workforce and the fall in access to care.

At the moment, general practice is absorbing the patients no one else wants, no one else manages and no one else will fund. The lucky patients, who respond to protocols, who can read, who have carers to advocate and money to spend find their way into care in the rarified world of hospitals, institutes and initiatives. The rest remain with us.

Before we nudge GPs out of their habitat and replace them with introduced species, it may be timely to consider what there is to lose. I’m not sure they will be easy to replace.