This deceptively simple question exposes some shaky philosophical foundations of medicine

In the deep south in the 1850s, an American physician noticed that the catalogue of human diseases was missing an entry. Nowhere in the medical literature was a description of the “disease of the mind” that caused slaves to run away.

And so, reflecting the racist views of the era, he coined the term “drapetomania” in a report read before the Medical Association of Louisiana and published in the New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal.

“In noticing a disease not heretofore classed among the long list of maladies that man is subject to, it was necessary to have a new term to express it,” Dr Samuel Cartwright said.

The “troublesome practice” of slaves bolting for freedom could be almost entirely prevented with the “advantages of proper medical advice, strictly followed”, he wrote.

History, sadly, is littered with perverse uses of medical authority, many of which hinge on the re-drawing of disease boundaries.

Throughout the 19th century, female masturbation was described as a “moral leprosy” that caused (among other things) “hopeless insanity”, cancer and heart problems, and some surgeons performed clitoridectomies in an attempt to cure it.

Homosexuality was inappropriately pathologised in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until 1973, and extremely unethical attempts were made to treat it through electric shock therapy, ice-pick lobotomies, and chemical castration.

Today, the American Psychiatric Association strongly opposes any psychiatric treatment based upon the assumption that the patient should change their sexual orientation.

But historical evils cast long shadows. It was only this year the WHO removed all mention of homosexuality from the new International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), saying there was no evidence that homosexuality needed to be medicalised.

The earliest version of the ICD, released in 1948, listed homosexuality as a sexual deviation related to an underlying personality disorder. From 1992, homosexuality was loosely associated with a psychological disorder known as “egodystonic sexual orientation”.

Another major transformation this year was the removal of gender incongruence from the mental health chapter of the ICD, and its placement in a newly created “sexual health” chapter in an effort to prevent stigma.

You could view these developments through the lens of objectivity; as science marches forward, our ignorant, damaging ideas about what counts as a disease are slowly being corrected.

Or you could say that disease is a relative term, which simply gets attached to whatever society deems undesirable or abnormal at the time. We aren’t getting closer to an objective truth, we’ve just changed our values.

Philosophers sit at both poles, and, despite 40 years of arguing, they are no closer to reaching an agreement on the question of what makes something a disease.

Professor Christopher Boorse, a philosopher at the University of Delaware in the US, first articulated his view in his famous 1977 paper, which dispassionately defined diseases as “internal states that depress a functional ability below species-typical levels”.

Essentially, every organ, cell, structure and genetic code inside the human body has a specific function, and a disease is a theoretical notion that flags when something is so broken that it puts the individual outside the norm for their sex or age.

In an email exchange with The Medical Republic, Professor Boorse said the motivation behind his “biostatistical theory” of disease was to provide an objective framework for criticising political distortions of psychiatry, such as the former Soviet Union’s diagnosis of political dissidents with “sluggish schizophrenia”.

But, as Professor Boorse readily admits, hardly anyone in the literature agrees with him.

In a recent paper, Professor Jenny Doust and her colleagues, used the example of polycystic ovary syndrome to demonstrate that Professor Boorse’s theory was “irrelevant” and “unhelpful”. Polycystic ovary syndrome is diagnosed according to three variables: circulating androgen levels, regularity of ovulation, and presence of cysts in the ovaries. But there are two competing ways of mashing these three variables together. The Rotterdam criteria diagnose 18% of women with the condition, and the NIH criteria diagnose 9% of women.

Biostatistical theory offers “insufficient and counterintuitive guidance”, and cannot resolve this conflict, says Professor Doust, who is an epidemiologist at Bond University in Queensland.

Professor Boorse’s theory also cannot solve the line-drawing problem that arises as diagnostic tests for myocardial infarction become extremely sensitive. His theory labels the presence of minute amounts of myocardial necrosis a “trivial disease”, the authors say.

“I recognise species-atypical dysfunction at any level, including cellular, as pathological – and so does the discipline called pathology,” Professor Boorse responded.

“Whether a condition is pathological is a scientific question, not a value judgment, and it has none of the practical implications that people often assume it has.

“These and other writers seem to be asking how serious a pathological condition must be for us to call it a disease. But there is no medical answer to this question. In my view, it’s all disease of greater or lesser severity.”

On the opposite end of the spectrum, philosophers such as Joseph Margolis, William Goosens, Peter Sedgwick, and Hugo Tristram Engelhardt believe that definitions of disease are solely a function of our values.

It is the meaning that humans attach to certain conditions that gives rise to concepts such as disease, not the intrinsic characteristics of the conditions themselves, they argue.

“The fracture of a septuagenarian’s femur has, within the world of nature, no more significance than the snapping of an autumn leaf from its twig,” writes philosopher Peter Sedgwick.

In the middle of these two extremes sit the hybrid theories, which twist objectivity and value-based thinking together.

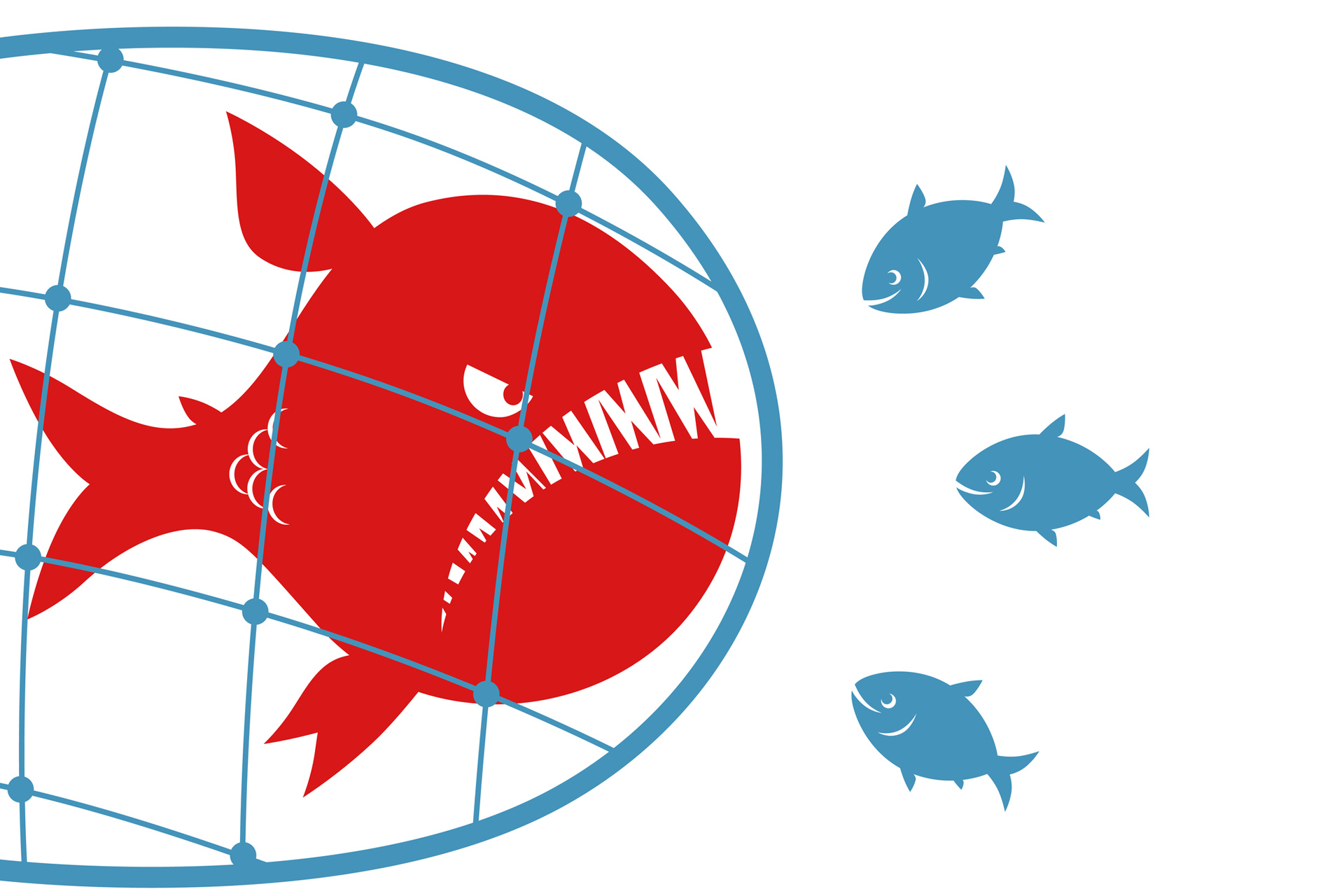

Two such theories include Jerome Wakefield’s harm-dysfunction analysis and Lennart Nordenfelt’s conceptualisation of disease as something interfering with major life goals, such as welfare and happiness. Each of these theories acts like a fishing net, trying to catch the true diseases while letting non-diseases swim through the holes.

But, as Professor Boorse describes in his 2011 overview, each has its own inadequacies; biostatistical theory makes one prematurely dead cell pathological, Wakefield’s theory states that conditions such as fused toes and albinism aren’t disorders (even though these are listed in the ICD-11), and Nordenfelt’s theory allows a patient who is very frustrated by a normal physical condition to be seriously ill.

After decades of thought, Professor Boorse says he feels “less confident” about the definition of disease than when he started.

The wars over disease definitions have high stakes and many stakeholders.

For doctors, disease labels are a shortcut for explaining the underlying biology and arriving at treatment options. For epidemiologists, having a lingua franca through the ICD aids global data linkage. Words describing disease carry the medical profession’s stamp of authority, which helps communicate the seriousness of a problem to government and the public.

But these different agendas don’t always align.

For instance, sarcopenia gained a disease label in the ICD in 2016, which helped spread awareness, attract funding and spur research. But the Australian Rheumatology Association still prefers to talk about “age-related muscle reduction” caused by disuse, as this inspires people to think of physical activity as the obvious treatment.

Values often clash, too. Society at large views autism or deafness as profound disadvantages, but the people living with these conditions are often deeply hurt by language that pathologises a core part of their identity. Deafness isn’t a disability, they say. It’s a difference that grants deaf people access to a cultural and linguistic minority group. And some people with autism find more comfort and truth in words like “neurodiversity” than blunt words such as “disorder”.

Other patients cling to the disease framework because it helps them understand the problem they are experiencing, gives them hope there is a treatment, relieves them of personal responsibility for their symptoms, and makes them feel less alone.

For example, chronic fatigue syndrome isn’t recognised by the ICD, but it’s used by millions of patients around the world to describe their debilitating condition. Similarly, patients have united under the umbrella term “Lyme-like illness” to fight for recognition in Australia. These patients believe they contracted the same chronic disease from the bite of a tick, but there is no research, as yet, to back up their claims.

The benefits of diagnosis are sometimes given to one group at the expense of another, which seems unfair. Dyslexia, for instance, is a term that medicalises poor reading ability.

But some people argue that diagnosing dyslexia is inherently inequitable. Children from less privileged backgrounds who struggle to learn how to read, but do not qualify for a diagnosis of dyslexia, are not given access to the same resources as richer children with dyslexia.

Sometimes doctors engage in academic disputes about disease definitions among themselves. Obesity, for example, is listed as a disease the American Medical Association, and is labelled a “nutritional disorder” by the WHO. But in Australia, the AMA and the RACGP still describe it as a risk factor.

Those in favour of calling obesity a disease say it is a form of dysfunction associated with genetic factors, co-morbidities and a lower quality of life. Those on the other side of the debate argue that people put on weight in response to an obesogenic environment, not because of an underlying dysfunction.

Disputes over disease seem so intractable and get so heated because there are too many conflicting priorities, Associate Professor Dominic Murphy, a philosopher of science at the University of Sydney, says.

“It’s hard to capture our existing notions of disease in a scientific way because they have a whole lot of non-scientific baggage that they carry,” he says.

Without a clear set of principles around what makes something a disease, there is little conceptual resistance to the runaway expansion of disease definitions, Professor Wendy Rogers, a philosopher at Macquarie University who was previously a general practitioner, says.

At the stroke of a pen, the majority of the population can go from being fit and well to plagued by chronic disease overnight; for example, the prevalence of osteoporosis in US women over 65 swelled from 21% to 72% after a definition change in 2008. The cavalier re-drawing of disease boundaries means that people at very low risk of future ill health are now being told they have very serious and worrying conditions, such as cancer, hypertension, prediabetes, and chronic kidney disease.

Overdiagnosis, or the slapping of disease labels on healthy people, causes distress and diverts health resources away from genuinely sick patients.

Many diseases sit on a continuum, where any cutoff point becomes a battleground.

But there are more rational ways to make these hard calls, says Professor Rogers.

In her recent paper, she hammered in a few signposts to guide doctors through the philosophical swamp. She proposed using a definition of disease that combined the idea of “significant risk” with traditional concepts of “dysfunction” and “severe harm” in order to combat overdiagnosis.

GPs use this conceptual framework intuitively when they avoid using words such as cancer, chronic kidney disease and hypertension to describe conditions that are easily managed and pose no serious threat to the patient, says Professor Rogers. “Sometimes the disease label is harmful,” she says.

Who benefits from the confusion?

As novelist George RR Martin warns us, “chaos is a ladder” for those with sinister intentions. Commercial groups have much to gain from manipulating disease definitions; with every new disease label you can almost hear the associated “ka-ching” of the cash register.

“My response to overdiagnosis has been to look at who is medicalising risk and why,” Dr Ray Moynihan, a researcher at Bond University, says.

“I, and others, have been throwing more critical scrutiny onto the actual groups of people who sit in hotel rooms and draw lines on graphs that define cut offs for ill health.

“We’ve worked out that it is pretty much open slather. There are no rules, there are no government regulations.”

His 2013 PLOS Medicine paper found that 75% of the members of panels involved in lowering disease thresholds were tied to multiple drug companies. “And they were the same drug companies that stood to benefit if the disease definition had been expanded,” says

Dr Moynihan.

Accepting sweeping overdiagnosis as the new norm is “a total surrender to professional and commercial forces that have, for their own interests, been increasingly targeting the healthy”, he says.

Bond University’s overdiagnosis team published a basic checklist in 2017 to reform the process. The checklist, which lead author Professor Doust described as “the most important thing I’ll ever do”, lays out the steps that experts need to go through to justify widening disease boundaries.

The team has applied the checklist to the American Heart Association’s decision to lower the threshold for hypertension in a recent paper in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Their analysis found that 31 million more US adults would be diagnosed with hypertension under the new definition. Out of these, 4.2 million people would be recommended treatment.

But only about 20% of those receiving a new diagnosis would see a modest or large reduction in CVD risk. Around 80% were unlikely to benefit.

As “astounding” as it seems, the American Heart Association did not systematically examine the potential harms before making their decision, Professor Doust says.

The move was frowned upon by the American College of Physicians and the American Academy for Family Physicians, which both rejected the widening of the definition of hypertension.

Vera Dimitropoulos, who co-directs the organisation responsible for modifying the ICD for Australia, says governance structures, stakeholder engagement and communications are the best way to resist the influence of lobbyists and make meaningful, evidence-based decisions on what should be included in health classifications.

The Australian Consortium for Classification Development engages with many different stakeholders in developing each edition of the ICD-10-AM, including clinical advisers, the public, states and territories, the federal health department, the private health sector and The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care.

The Australian ICD technical group members understand that they are required to declare any conflicts of interests with the items on the agenda of each meeting. These minutes are not made public, however.

The WHO “cuts through the lobbyists” by taking public submissions and running all proposed changes through a series of committees and reference groups, says Ms Dimitropoulos.

The WHO is very mindful of the fact that clinical specialists may have their own particular agendas, so it enlists broad-based generalists, such as internal medicine specialists or researchers on their Medical Scientific Advisory Committee to offset this influence.

Members of ICD working groups need to fill in “foreseen conflict of interest” forms, but these are not made public, a WHO spokesperson says.

Jumping outside the framework

Philosophy has always been better at destroying concepts than creating them. But maybe this is why it is such a powerful discipline.

Over the past 40 years, philosophers have tried to define the category of disease in many different ways. Every attempt has been torn down by other philosophers, leaving a wasteland of broken theories.

For some, this failure to define the word disease paves the way for a language revolution.

“We could keep looking for the correct definitions of ‘health’ and ‘disease’ but this paper advocates a different approach,” Professor Marc Ereshefsky, a philosopher at The University of Calgary in Canada, writes.

“Instead of trying to find the correct definitions of ‘health’ and ‘disease’ we should explicitly talk about the considerations that are central in medical discussions, namely state descriptions (descriptions of physiological or psychological states) and normative claims (claims about what states we value or disvalue),” he says.

Whether or not a particular state fits into the disease category is irrelevant to most medical decisions, he argues. By separating state descriptions from claims about whether those states are good or bad, “we get to the issues that matter in medical discussions, thus rendering the terms ‘health’ and ‘disease’ superfluous”, he says.

Some philosophers have adopted this approach, “but not all”, Professor Ereshefsky tells The Medical Republic. “Some worry that value judgments will always creep into state descriptions,” he says.

Professor Ereshefsky does not deny that science is infused with normative values. The goal of his theory is to expose normative claims masquerading as neutral statements wherever possible.

“State descriptions will never be completely value-neutral, but we can do our best to label value judgments as such when they are identified,” he says.

But, even if doctors recognise the defects in the notion of disease, they will never abandon it, Richard Smith, the editor of the British Medical Journal until 2004, says in a call from London.

“One thing I think doctors never really realise is that behind every way of thinking there is a theory,” he says.

“They just think this is how the world is.”