None of us signed up for what general practice has become.

I am one of those people who knew at an early age what they wanted to be when they grew up.

At three years old, I drew a very primitive picture of “Elizabeth’s Hospital” (a box-shaped building with oblong windows and triangular roof, complete with TV antenna and flowers) on a pre-school placement. While my drawing skills are pretty much the same now, the dream of being a doctor in Australia has been transmuted from placemat to reality.

I’m one of the lucky ones.

Or am I? Is living your dream all it’s cracked up to be?

Honestly, the constant negative chatter around general practice is soul-destroying.

From celebrities who publicly declare that anyone can do what a GP does (happy to supervise a session any time, by the way; celebs and politicians both welcome), to expanded scope of practice for pharmacists and nurses (with commensurate reduced scope for GPs who, therefore, see less of these presentations, or worse, shared liability), as well as the introduction of other service providers who feel it’s permissible to offer cherry-picked elements of general practice for the cost of a gap fee that I’m forbidden from charging. I’m looking at you Bupa, HealthyLife and Priceline, among others.

It’s no wonder GPs and clinics are feeling disillusioned and burnt out.

To these issues, add the heightened complexity of what’s covered in a consultation (personally, my caseload is more than 95% chronic health conditions, mental health and domestic violence), that Medicare billing seems to be in a constant state of flux (with the PSR spectre haunting the background) and the perpetual battle to balance the financial needs of the patient, practice and clinician.

Truly, it’s a miracle most of us aren’t rocking in a corner.

And it’s not like the list stops there either.

CPD changes must be complied with, AHPRA fees have increased and are markedly above what other healthcare professionals pay (why being the obvious question), and college membership and CPD home considerations must be weighed up.

Then there’s practice accreditation, privacy and financial consent legislation and that whole pandemic thing. Personal matters might occasionally need some attention too.

And don’t even get me started on the payroll tax minefield … a state government-based anti-growth tax that bludgeons (sorry, incentivises) practices to comply with the federal government’s Medicare bulk-billing targets.

Anti-growth, really? For example, I’m aware of a practice that’s considering reducing its hours just to stay under the payroll tax threshold.

Potential political gain from bulk-billing aside, the assumption that “free” healthcare equals good healthcare is flawed.

Does anyone stop to ask patients and GPs what they reallywant in their healthcare experience? Bulk-billed, high-turnover, low-value, up-sized “would you like fries with that shared health summary upload so we can hit our quarterly PIP target” medicine is unsatisfying medicine.

GPs are all too aware of the cost-of-living pressures that exist in our communities and are open to considering bulk-billing patients experiencing financial hardship.

Related

The problem is in the lack of choice and control over our fees for the services that we, as independent businesses, provide, thanks to the threat payroll tax poses to the clinic’s business. Is anyone expecting their non-GP specialist, solicitor, accountant, hairdresser, grocer, school etc. to halve their fees? And is that person or business financially penalised for charging its listed fee? And will channelling WIP payments through the clinic’s account help or hinder the cause?

Hmmm …

With my clinic owner’s hat on, the other impact of payroll tax that I’ve not seen discussed anywhere is whether we’re inadvertently white-anting the value of our clinics to avoid payroll tax exposure and vicarious liability for medical malpractice.

If contracts give ownership of the patient notes/list to the independent/tenant doctor who is servicing his/her own patients, not practice patients, what do I now have to sell?

Chairs, desks and some very nice, only slightly out-of-date wall art, yes, but no longer a practice-owned patient base. I’m just going to leave that here for us all to think about. Those with more knowledge on the matter are most welcome to weigh in.

In our clinic team meetings, we GPs discuss all of the above and the toll it takes on morale.

We know there’s a shortfall in doctors taking up GP registrar positions. Some GPs, myself included, choose to remain in part-time practice due to competing priorities and, frankly, a lack of desire to pick up more consulting time.

Now, with AHPRA considering “fitness to practise” assessments for doctors aged over 70 years and some medical indemnity insurers offering “retirement reward” payments, it’s clear that the pool of practitioners available to meet demand is diminishing.

I’d much rather spend my team meeting time discussing how we can improve, expand or diversify patient care, especially rurally where I’m based. But alas. The negative narrative often prevails and we ponder whether there is, in fact, an engineered system failure occurring for the sake of steering Australian general practice towards an NHS-style model of care.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I don’t believe that the solution lies in opening more bricks-and-mortar GP services.

The rate-limiting step in the system is the lack of troops, not buildings. Establishing yet more urgent care clinics or entirely new “free” GP clinics (1000 of them if you’re the Greens – but they’re not free, taxpayers are paying) doesn’t add anything, except perhaps the photo opportunity to cut a ribbon. Rearranging chairs on the Titanic is the image that comes to my mind.

I am absolutely an advocate for redirecting money earmarked for these new GP premises that will be staffed from the existing GP pool in direct competition with existing GP practices (whose doctors have now been poached) towards improved remuneration for GPs and clinics via higher Medicare rebates.

Medicare rebates that approach (or even exceed!) the modern pay rates of equivalently trained and experienced professionals could send GP bulk-billing skyrocketing overnight while maintaining existing therapeutic relationships, addressing the out-of-pocket expense concerns of patients and the flow-on effects to emergency departments, to say nothing of its effect on GP morale, recruitment and retention.

I challenge you to find another job that pays the same rate to someone working their first day as another working their last day of a 40-year career.

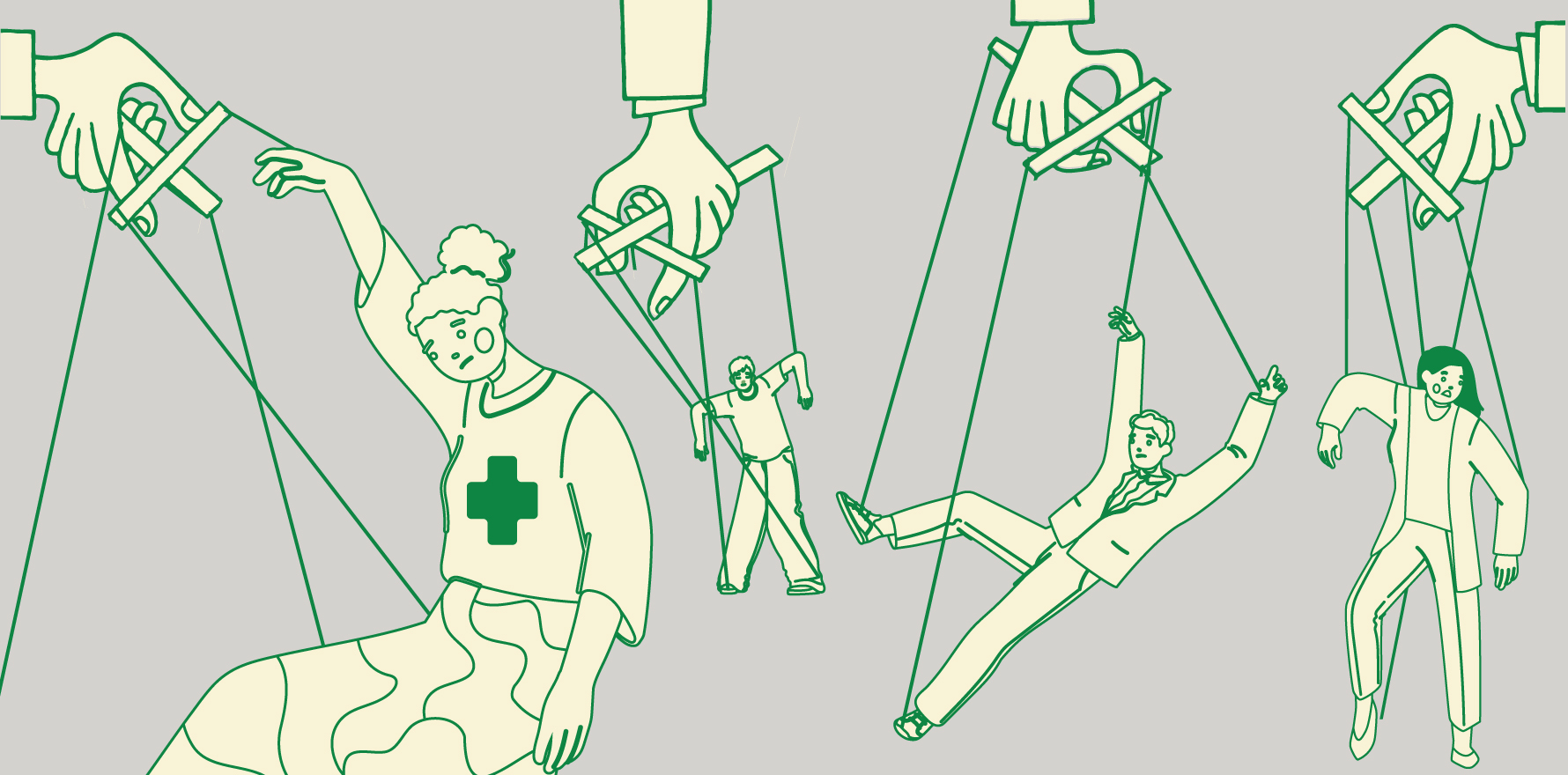

Ultimately, the heart of the matter is the feeling that what GPs do is not valued adequately and that we are powerless to change it. It’s only by addressing this properly and permanently that the negative narrative tide will turn and I’ll feel less like a medical marionette.

For what it’s worth, I still have that placemat from pre-school. The dream of being a contented, productive doctor in Australia lives on.

Dr Elizabeth Hicks is a GP and author from the northern rivers region of NSW.