Eosinophilic oesophagitis is a chronic, life-long condition requiring regular reviewing to monitor for clinical improvement or regression

Eosinophilic oesophagitis is an increasingly recognised chronic immunological condition of the oesophagus. It should be suspected in children with persistent feeding difficulty or swallowing problems, especially if allergic or atopic conditions are present, including cow’s milk protein enterocolitis in infants, eczema, and asthma.

There is tremendous overlap of symptoms with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), so this should always be considered in children with symptoms refractive to reflux treatment. In rare circumstances, it has been reported in patients at the time of diagnosis of coeliac disease.1

Epidemiology

Meta-analysis studies show incidence ranges from 0.7 to 10/10,000 per person-year and prevalence from 0.2 to 43/100,000.2 The prevalence seems to be highest in children with food impaction or dysphagia (63% to 88%) and it is the most common cause of food impaction in children. In patients undergoing endoscopy, eosinophilic oesophagitis is diagnosed in 2% to 7% of patients.3

It is more common in males in both adults and children4 and multiple studies have confirmed that the majority of children with eosinophilic oesophagitis also have atopic conditions such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, dermatitis and IgE-mediated food allergy.5-7

Pathophysiology

Eosinophilic oesophagitis is defined as a chronic, antigen-mediated oesophageal disease, characterised by eosinophilic inflammation.8 Eosinophilic oesophagitis is thought to occur in genetically susceptible individuals, with atopic tendencies, where T-helper type 2 mediated inflammation is triggered by exposure to either food or environmental allergens.9

In paediatric eosinophilic oesophagitis, the inflammatory process is thought to predominate, leading to feeding difficulties, pain and heartburn, while in adult eosinophilic oesophagitis, fibrosis predominates, resulting in strictures and dysphagia.10

Oesophageal re-modelling has been seen in untreated eosinophilic oesophagitis in even young children.11 Stricture formation is less common in children, and is thought to be a consequence of long-term chronic inflammation.12 There is a clear association between duration of untreated symptoms prior to diagnosis, and likelihood of strictures at diagnosis in adults.

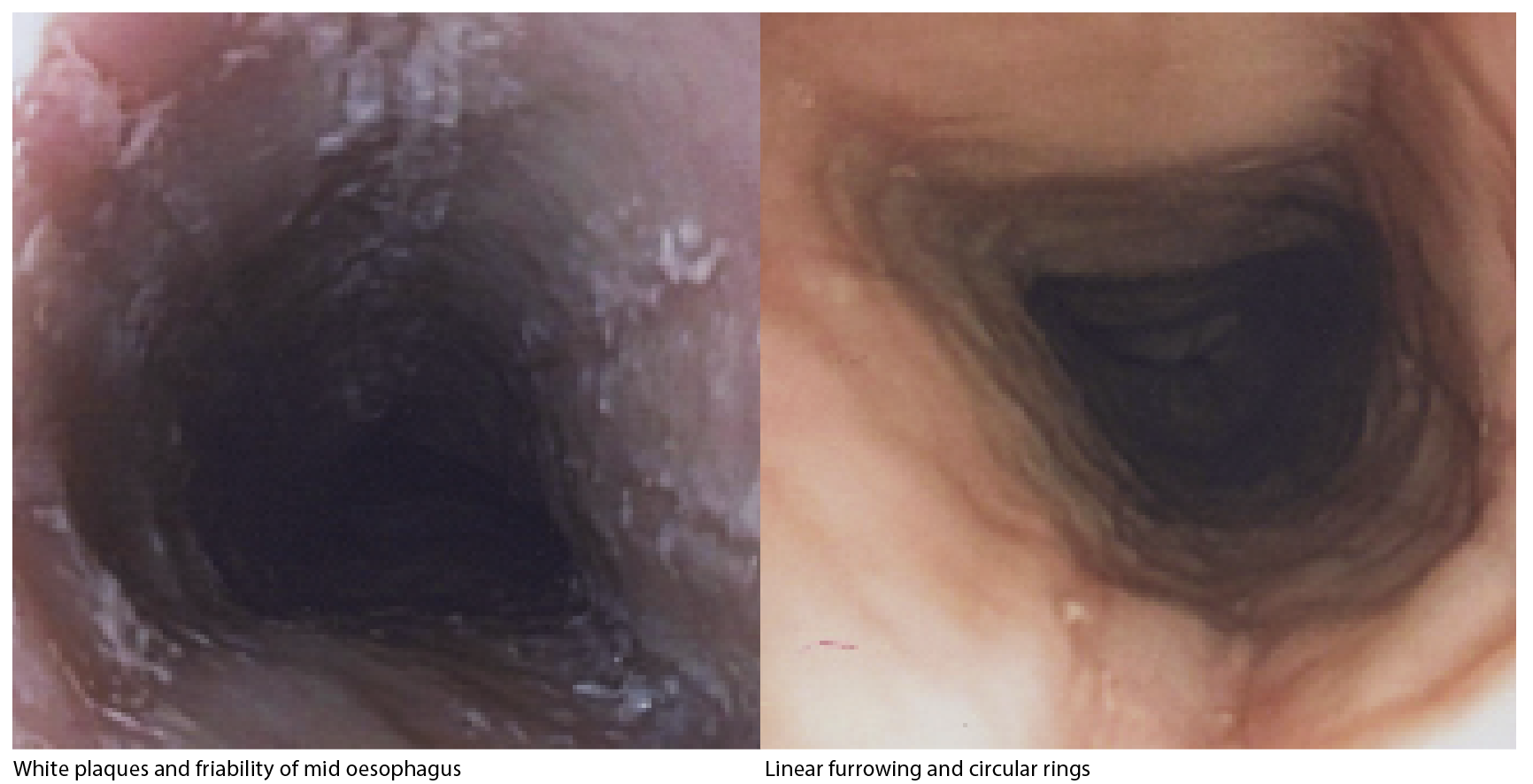

Eosinophilic oesophagitis is diagnosed by histopathological confirmation of eosinophilia following oesophageal biopsy (eosinophil counts ? 15/hpf). Other microscopic findings include oedema, eosinophil degranulation, subepithelial hyalinisation and significant basal cell hyperplasia. Endoscopically the classic appearance includes circular rings (trachealisation), linear longitudinal furrows, white plaques, and friability and, less commonly, strictures. (see images above)

Clinical features

Symptoms of eosinophilic oesophagitis are a result of oesophageal dysfunction and include:

• feeding difficulties

• texture aversion

• failure to thrive

• vomiting

• regurgitation

• food impaction

• abdominal and chest pain

• dysphagia

Although often reported as a separate entity to GORD, our clinical experience is that patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis almost universally have co-existing clinical and endoscopic evidence of GORD, even when eosinophilic oesophagitis treatment is successful.

Eosinophilic oesophagitis should be part of the differential diagnosis in infants with the triad of significant atopic eczema, GOR symptoms and milk/soy protein allergic colitis. Similarly, toddlers and older patients with long-standing history of GOR symptoms with texture aversion (often meat product), and/or a minimal response to proton pump inhibitors (PPI) on a background of atopy, also warrant referral to a paediatric gastroenterologist for further evaluation.

Laboratory findings in eosinophilic oesophagitis are mostly non-specific, and include low ferritin secondary to red-meat avoidance due to dysphagia and texture aversion.

Recent publications have also described elevated TTG antibodies in a number of paediatric eosinophilic oesophagitis patients, in the absence of coeliac disease.13 Other reported laboratory findings include elevated IgE and eosinophilic cation protein (ECP) and high blood eosinophil count.14 Unfortunately, as these are also often raised in allergic conditions, they are of little value in monitoring of disease progression and response to treatment.15

Regular endoscopy and histological review of oesophageal biopsy is the only method of monitoring clinical success.

In infants, the triggers are more likely to be food protein antigen, such as cow’s milk protein, but allergy tests often fail to identify food antigens in older children.

Skin prick testing and serum food specific IgE testing may yield an ingested food trigger, with milk still the most common allergen identified.16

Food-patch testing in combination with skin-prick testing may prove more useful,17 but is difficult to complete due to poor compliance in ensuring the food stays adhered to skin for 24 hours.

Studies have indicated a seasonal pattern to symptom onset,18 suggesting an association with aeroallergens, such as pollen and dust mite, which again may be difficult to identify on standard allergy testing.

Treatment

Treatment for eosinophilic oesophagitis is aimed at symptomatic and histological improvement, and to reduce and prevent complications such as fibrosis and strictures. Steroid therapy and dietary manipulation are the two main arms of consensus treatment guidelines.19

Anecdotally, our highest clinical success is seen with a combination of PPI and an oral topical steroid to coat the lining of oesophagus, along with the oral mast cell stabiliser, ketotifen. Topical steroid can involve using fluticasone inhaler, but given orally by mouth. Alternately, budesonide respule liquid can be mixed with various mediums to create a slurry and given orally. Oral steroids have been successful in reversing oesophageal fibrosis in children, but not adults.20

The high first-pass metabolism of enterally absorbed fluticasone and budesonide help avoid cushingoid side-effects.

A recent publication has demonstrated the safety of long-term topical oral steroids in children, with minimal impact on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and low rate of oesophageal candidiasis.5

In infants with suspected milk protein as the antigen, elimination of dairy protein orally is advised, with amino acid formula as a dairy alternative.

In older children, an empiric six-food elimination diet (milk, soy, nuts, seafood, wheat and eggs) is successful for some, but compliance is difficult long-term, with significant impact on quality of life.21 Recent publications suggest that a four-food elimination diet (dairy, eggs, wheat and soy) has almost equivalent results as the six-food elimination.22

Complications such as stricture formation may require more aggressive treatment, including potential endoscopic balloon dilatation.

Monitoring and follow-up

Eosinophilic oesophagitis is a chronic, life-long condition. Symptoms and endoscopic signs re-occur in the majority of patients, weeks to months after treatment is stopped.23

Children with eosinophilic oesophagitis need regular review to monitor for clinical improvement or regression.

They are likely to need further endoscopies and biopsies, even after symptoms have improved, to ensure that any changes in medications or diet are successful.

Dr Reuben Jackson is a paediatric gastroenterologist at Prince of Wales Private Hospital, Randwick, NSW. Dr Samantha Tilakaratne is a paediatric gastroenterologist practising at Randwick Specialists, NSW. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References:

1. Ooi C, Ooi CY, Day AS, et al. Eosinophilic Esophagitis in children with Celiac Disease; J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008 Jul;23(7 Pt 1):1144-8. Epub 2007 Dec 7 doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007

2. Soon IS, Butzner JD, Kaplan GG, et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013 Jul;57(1):72-80.

3. Dellon E. Epidemiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014 June; 43(2):201-218

4. Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, et al. 14 Years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:30–6.

5. Andreae D, Hanna MG, Magid MS, et al. Swallowed Fluticasone Propionate is an Effective Long-Term Maintenance Therapy for Children with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Aug; 111(8):1187-1197

6. Sugnanam KK , Collins JT, Smith PK, et al. Dichotomy of food and inhalant allergen sensitization in eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy 2007; 62: 1257-1260

7. Spergel JM. Book WM, Mays E, et al. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300-306

8. Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:3–20e6.

9. Merves J, Muir A, Modayur Chandramouleeswaran P, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;112:397-403

10. Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, et al. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014 Apr;79(4):577-85

11. Chehade M, Sampson HA, Morottin RA, et al. Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. . J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;45: 319-28.

12. Singla MB, Chehade M ,Brizuela D, et al. Early Comparison of Inflammatory vs Fibrostenotic Phenotype in Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Multicentre Longitudinal Study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol . 2015 Dec 17;60:e132)

13. Le Fevre AK, Walker MM, Hadjiashrafy A, et al. Elevated Serum tissue Transglutaminase Antibodies in children with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. JPGN 2017;65 :69-74

14. Gupta SK. Noninvasive markers of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2008;18:157-67.

15. Rodríguez-Sánchez J, Gómez-Torrijos E, de-la-Santa-Belda E, et al. Effectiveness of serological markers of eosinophil activity in monitoring eosinophilic esophagitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2013;105:462-467.

16. Erwin EA, James HR, Gutekunst HM, et al. Serum IgE measurement and detection of food allergy in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010 Jun;104(6):496-502.

17. Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A, et al. Identification of causative foods in children with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with an elimination diet. J Allergy Clin Clin Immunol. 2012;130:461-467

18. Fahey L, Robinson G, Weinberger K, et al. Correlation between aeroallergen levels and new diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis in New York City. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017; 64:22–5.

19. Papadopoulou A, Koletzko S, Heuschkel R, et al. Management Guidelines of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Childhood. JPediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2014;58: 107–118

20. Dohil R, Newbury R, Fox L, et al. Oral viscous budesonide is effective in children with eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2010;139:418-429

21. Lucenda AJ. Meta-analysis-Based Guidance for Dietary Management in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:464

22. Kagalwalla AF, Wechsler JB, Amsden K, et al. Efficacy of a 4-food elimination diet for children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastgroenterol Hepatol (Internet)2017. Published online June 8. Available from http//dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.048

23. Menard-Katcher P, Marks KL, Liacouras CA, et al. The natural history of eosinophilic oesophagitis in the transition from childhood to adulthood. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013; 37:114-121