Dry eye disease (DED) is common, often chronic and can be challenging to manage.

Dry eye disease (DED) is common, often chronic and can be challenging to manage.1-3

Early detection and treatment with topical lubricants — such as MURINE® Dry eyes — is an important first step in managing mild to moderate DED, helping to relieve uncomfortable symptoms while aiding maintenance of a stable tear film.3,4

Why patients seek help

DED is one of the most common eye problems a GP or pharmacist has to deal with, and the leading reason patients visit optometrists and ophthalmologists.4,5

Patients with DED frequently describe irritation of the ocular surface as feelings of dryness, grittiness, burning or stinging sensations, and itching.6 Eye discomfort may also trigger reflex tearing, fluctuating vision, blurring, light sensitivity or redness.6

Although common — affecting an estimated 20% of adults4 — DED is often difficult to identify and can go unrecognised.4,5 Symptoms can vary day-to-day and from person-to-person, often co-exist with other conditions or feel worse under certain conditions.6

Dry eye disease

Dry eye is a complex disease caused by a range of disorders affecting tear film stability and is associated with ocular discomfort or irritation, visual problems and inflammation.2 Most patients are now thought to have varying combinations of the two DED subtypes3:

- Aqueous deficient dry eye — related to tear underproduction

- Evaporative dry eye — related to meibomian gland dysfunction.

There are many predisposing factors that can negatively affect tear film stability and function, many of which are linked to who we are, how we live and other health conditions including:

- Drying workplace or home environments7

- Smart phone, tablet and computer use7,8

- Wearing contact lens7

- Diets deficient in vitamin A9

- Being female7,10

- Aging11

- Some health conditions (e.g. autoimmune diseases, endocrine conditions) 9,11,12

- Certain systemic medications (e.g. antihistamines, beta blockers, diuretics) 12

- Some ophthalmic surgeries (e.g. cataract, refractive or lid surgeries) 12

- Preservatives in topical eye medications may aggravate DED.12

When to treat – when to refer?

Most patients will have mild DED and can be managed in the primary setting with appropriate self-management and over-the-counter topical lubricants (tear supplements) such as MURINE® Dry eyes.4

When symptoms are more severe or there are risk factors present (such as a refractory disease that requires more aggressive intervention to reduce the risk of permanent ocular surface damage) patients need to be referred to an optometrist who can perform specialised eye examinations — with referral to an ophthalmologist and other specialists if required.4

DED symptoms that may indicate a referral is need include4,5:

- Partial or no relief when using eye drops

- Visual blurring and fluctuation

- Moderate to severe eye pain

- Reduced visual acuity

- Eye redness

- Light sensitivity.

The role of lubricating eye drops

Early diagnosis and treatment of DED are important to help prevent disease progression before it becomes a ‘self-perpetuating’ condition.3

The use of lubricating eye drops provides symptom relief and aids in tear film stability. They are an important first step in managing the early stages of the condition along with patient education, dietary and environment modifications, lid hygiene and identification of contributing factors such as topical or systemic medications.3

Topical lubricants have a soothing, palliative effect while decreasing the number of inflammatory cells at the ocular surface, enhancing tear retention time and viscosity, and reducing inflammatory processes caused by increased osmolarity.13 However, their effectiveness can be limited by their duration of action.

Ocular lubricants are first-line therapy for mild DED and an adjunct to more advanced therapies in moderate and severe DED.3,13

Why treat dry eyes with MURINE® Dry eyes?

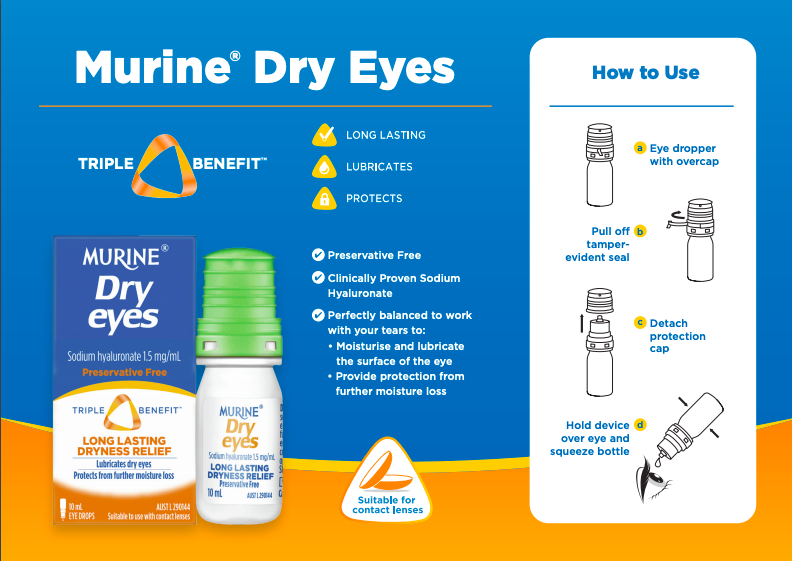

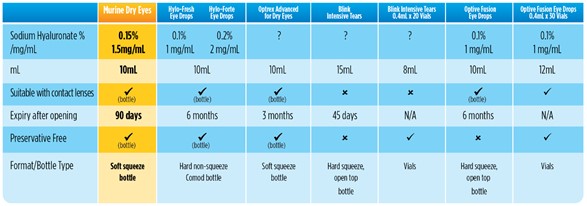

Not all topical lubricants are the same. 3,13 MURINE® Dry eyes is a specially formulated preservative-free ophthalmic solution that is indicated for dry eyes and offers three benefits for the patient:

- Long lasting dryness relief

- Lubricates dry eyes

- Protects eyes from further moisture loss.

MURINE® Dry eyes contains clinically proven sodium hyaluronate3,13:

- A natural component of the tear film

- Has intrinsic properties of water retention, viscoelasticity, and promotes corneal epithelial wound healing

- Increases viscosity, hydrates and lubricates the ocular surface.

Preservative-free MURINE® Dry eyes comes in an easy-to-use soft-squeeze bottle with a patented filtration system to keep bacteria out during use — making it is suitable for patients who are:

- Allergic or sensitive to preservatives

- Want to continue wearing contact lenses

- Have problems using hard non-squeeze bottles.

MURINE® Dry eyes can be found in pharmacy retailers at $14.95RRP.

Download the patient counselling guide for Murine® Dry eyes here.

For further information contact Care Pharmaceuticals: FREECALL Australia 1800 788 870 www.murine.com.au

References

- Uchino M, Schaumberg DA. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2013;1(2):51-7.

- Craig JP, et al. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276-83.

- Jones L, et al. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):575-628.

- Findlay Q, Reid K. Aust Prescr. 2018;41(5):160-3.

- Chan C. Dry eye disease: current status and improving care [Internet]. 16 March 2020. MJA Insight. https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2020/10/dry-eye-disease-current-status-and-how-we-can-improve-patient-care/ (accessed August 2020).

- Nichols KK. Ocul Surf 2006; 4(3):137-45.

- Willcox MDP, et al. TFOS DEWS II Tear Film Report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):366-403.

- Rossi GCM, et al. Int Ophthalmol. 2019;39(6):1315-22.

- Stapleton F, et al. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):334-65.

- Sullivan DA, et al. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):284-333.

- Sharma A, Hindman HB. J Ophthalmol. 2014; 2014:781683.

- Gomes JAP, et al. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):511-38.

- Simmons PA, et al. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015; 9:665-75.