New HIV infections can be easily missed and testing isn’t always straightforward. Here’s how to get it right

In Australia, key groups to target for routine, regular HIV testing include gay and homosexually active men, sex workers, people who inject drugs, people with culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, and Aboriginal people.1

Of new HIV diagnoses in Australia, 70% occur in men who have sex with men (MSM), but only 50% of this high-risk group report testing at their GP.2 For heterosexuals, testing for HIV in primary care is much more common.

UNAIDS has committed to end AIDS by 2030 – a fast-tracked target, which builds upon the goal of 90-90-90:

• 90% of all HIV-positive people to know their status

• 90% of those diagnosed on treatment

• 90% of treated patients achieving viral suppression by 2020

Timely HIV diagnosis is key, and general practice has been identified as a priority setting for the testing to occur.1 Australia has committed to achieving the 90-90-90 goal, and primary care practitioners will play a vital role in its success. However, it can be tricky to identify the members of the priority populations in a primary healthcare setting, as distinguishing behaviours may not be readily volunteered.

Certainly, HIV infection is not limited to high-risk groups, and testing requires a low threshold of suspicion. In a HIV seroconversion study, over 10% of the respondents who had not tested for HIV in the previous 12 months, reported that their doctor didn’t suggest it.3

While regular HIV screening may help with early detection of the infection, another not-to-be-missed opportunity for early diagnosis occurs when patients present to their GPs with an acute HIV infection, or HIV seroconversion. Early diagnosis is extremely important for the patients and their partners, expediting engagement into care and offering the opportunity for early access to treatment.

Starting treatment in this early phase is associated with many long–term benefits. It can reduce the duration and severity of the acute infection and alter the virological set point, leading to the relative preservation of the immune function and a reduction of the rate of progression, resulting in reduced morbidity and better prognosis. Suppression of the initial burst of viral replication may dampen the extent of viral dissemination, thereby limiting the dimensions of the viral reservoir.

Suppression of viral replication offers a possibility of reducing the emergence of viral mutations, which may affect future medication efficacy. Suppression of rapid HIV replication and resultant viraemia during seroconversion may decrease the high risk of onward transmission during that time. Furthermore, a timely diagnosis of HIV infection provides the opportunity to affect behavioural change, also potentially decreasing the onward transmission risk. Starting treatment early may also give the patient some sense of control.

There are potential risks associated with early treatment, such as potentially longer exposure to antiretroviral drugs, development of medication resistance, drug toxicities and effect on quality of life associated with daily medication.

Early infection

In sexual transmission that follows the contact of HIV with the mucosal epithelium, infection occurs at local cells at the site of exposure within 12-24 hours. The dendritic cells located in the mucosa and lymphoid tissues are believed to be among the first cells to encounter HIV during sexual transmission. Within 48-72 hours, these dendritic cells mediate the spread of HIV to regional lymph nodes, where rapid viral replication occurs.

Simultaneous spread to other systems, including the gut, genital tract, skin and CNS occurs. In response to this surge of viraemia, host antibody is produced over the following 5-40 days, resulting in a decline and levelling out of plasma viral load, followed by relative host immune restoration and recovery of the CD4 T-cell population.

HIV seroconversion

HIV seroconversion describes the period post-HIV infection when antibodies to the virus are first produced and rise to detectable levels, from infection to seropositivity. Antibodies usually begin to appear about one to two weeks post-exposure, and are typically detectable within three weeks, depending upon the detection method; however rare cases have been reported of seroconversion many months post-infection.4

The interval following a new HIV infection is described in several ways:

• Acute HIV infection describes the period immediately after exposure and infection, during the initial burst of viraemia. During this time, HIV antibodies are undetectable, but HIV RNA or p24 antigen is present

• Acute primary illness, also termed seroconversion illness or acute retroviral syndrome, (ARVS) describes the group of symptoms characterising primary HIV infection

• Recent infection or primary HIV infection (PHI) is the interval from infection up to six months post infection

• Early HIV infection refers to either acute or recent HIV infection

Symptoms and signs

Clinically, a primary HIV infection can be accompanied by a seroconversion illness, a constellation of non-specific signs and symptoms, often described as a mild to severe flu-like illness. It is estimated that 40-90% of patients experience clinical signs and symptoms, which typically occur 10-14 days post-infection, but may occur from three days to 10 weeks.

Most commonly, symptomatic people will experience fever, lethargy, anorexia, myalgia/arthralgia and headache. Night sweats and diarrhoea occur less commonly. Clinical findings include lymphadenopathy, a maculopapular rash that can affect the palms and soles, face and trunk; mucosal ulceration is less common. In addition to signs of aseptic meningitis, rare neurological presentations include cranial nerve palsies, radiculopathy, encephalopathy and Guillain-Barre syndrome, which may necessitate hospital admission. Symptoms typically spontaneously resolve within two to three weeks, and most cases require only supportive management with bed rest and simple analgesics.

Given the non-specific nature of the seroconversion illness, diagnosis requires the watchful clinician to have a low threshold of suspicion for HIV testing. Recent diagnosis of another sexually transmitted infection (STI), sexual or other HIV risk in the context of a glandular fever-type presentation may alert the perceptive clinician to the possibility of HIV infection.

The New York State Department advises testing for HIV for anyone, regardless of reported risk, who presents with a flu-like illness, particularly when the patient reports a recent exposure or a newly-diagnosed STI, presents with a rash or aseptic meningitis, is pregnant or breastfeeding or is currently taking HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).5 Other triggers for testing include a recent change in sexual partner, or simply patient request.

Laboratory testing

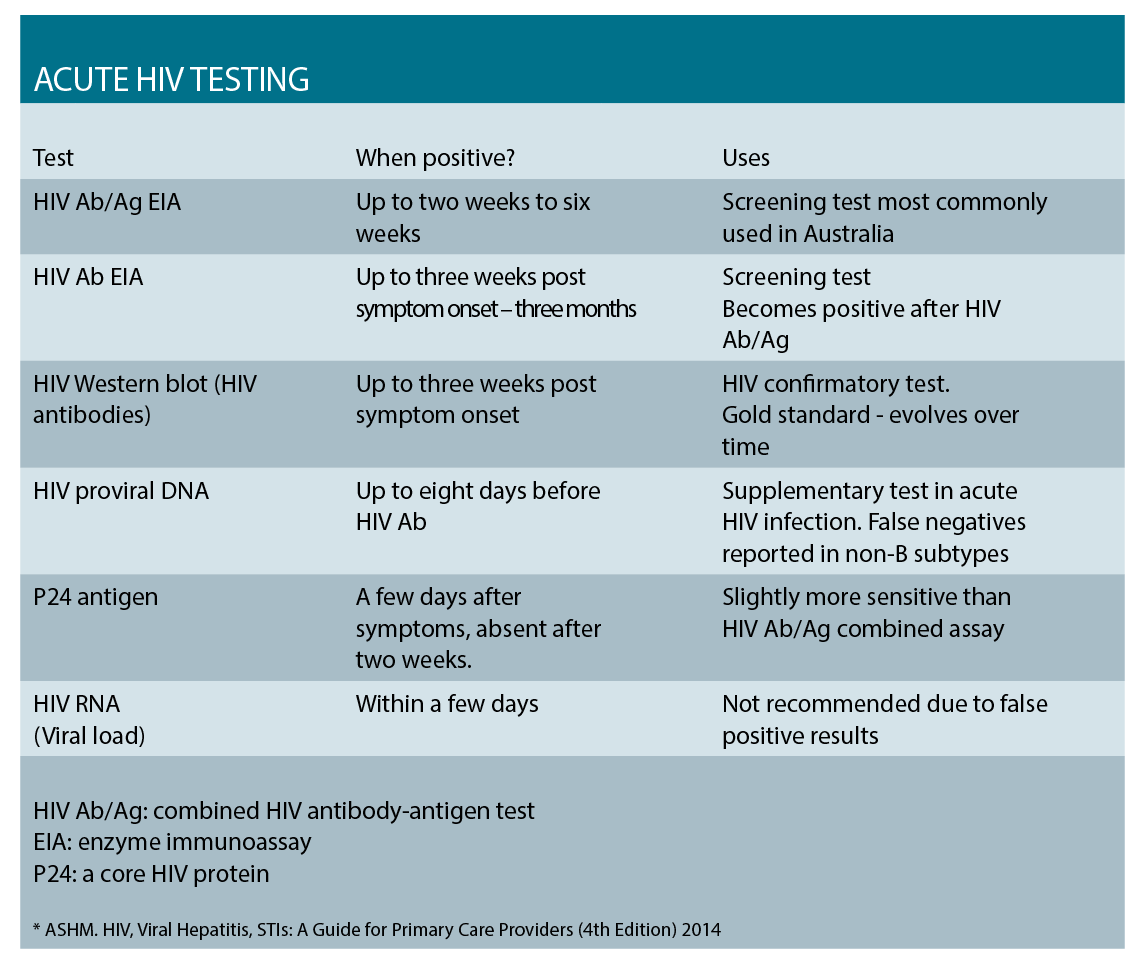

In the Australian context, the screening assay is usually the combined HIV antibody/antigen test. This combination assay can become positive two to six weeks post-exposure, boasting a six-week window period. This is a vast improvement over the previously used HIV antibody test with the window period of three months. Reactive screening assays are repeated in the laboratory, and HIV western blot (WB) – the gold standard for HIV diagnosis – is performed.

In the very early stages of infection, the western blot result may be negative or indeterminate, and supplementary testing may be required. Generally the first test to become positive in acute infection is the HIV viral DNA assay, followed by the p24 antigen, and then the HIV antibody. No single test is infallible, and often diagnosis is made considering the pattern of evolving results and clinical presentation.

Management

The great majority of patients can be managed in the community. Bed rest and symptomatic relief using simple analgesics and emetics are usually adequate. Patient counselling and psychosocial support should be considered, particularly where a definitive diagnosis is pending. Exploring patient supports and key concerns is important, and information regarding the implications of a positive result and current-day HIV prognosis should be discussed.

The risk of transmission and a range of harm minimisation issues should be addressed, including safe sex using condoms, no blood or tissue donations, avoiding breastfeeding and not sharing injecting equipment. Testing for other STIs should be offered, including chlamydia, gonorrhoea, syphilis and hepatitis B and C. As with all new HIV diagnoses, baseline testing is comprehensive and can be done by, or in consultation with, a sexual health clinic or a hospital-based HIV service. Some of these offer specialist counselling services.

Contact tracing is important for all newly diagnosed HIV infections, and while not an immediate priority, should be sensitively addressed soon after diagnosis. Tracing contacts within the previous 72 hours requires urgent attention, as these people may benefit from post-exposure prophylaxis. For other contacts, the time to trace back is determined by the onset of risk behaviour or last known negative HIV test result. As with sexual health contact tracing, the identity of the patient remains confidential. The preferred contact tracing method is provider referral, and patient consent is required.

Large studies have demonstrated the benefits of treatment in early infection.6,7 Antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV is recommended for all HIV-positive people, and Australian guidelines recommend that ART should be offered to people with early infection and started in all pregnant women as soon as possible.

A new HIV diagnosis is a time of

significant adjustment and upheaval for most people. Prior to commencing therapy, patients should be informed about the pros and cons of treatment, including medication side effects and risks, and the importance of adherence. Patients or providers may elect to defer treatment depending upon the individual patient circumstances and preferences.

Case scenario

Jan is a single, divorced mother of two teenagers, and has recently returned from a trip to Spain. She presents with non-specific flu-like symptoms including muscle aches and pains, fever and headaches,

and has been confined to bed for the last few days. You notice she has a rash and conduct a brief risk assessment for HIV.

Jan says that while on holiday she met Clive, a Briton, with whom she had sex a few times, only using condoms on the first occasion. As well as testing for other potential causes of Jan’s symptoms, you advise testing for HIV and STIs. Jan has been vaccinated for both hepatitis A and B.

After explaining the reasons for HIV testing and the implications of possible results – positive, negative and indeterminate – you obtain informed consent. You collect serology for HIV screening (HIV Ab/Ag combined assay), STI testing (syphilis serology, a patient-collected vaginal swab for chlamydia and gonorrhoea PCR) and arrange for Jan to return for her results a week later. During this time you advise

Jan to abstain from donating blood. Jan reports she feels too unwell to have sex. Jan had not considered HIV and feels this is unlikely. Despite this, you explore her support networks and advise against unnecessary disclosures.

Three days later, the lab reports that the HIV Ab/Ag combined screening assay test was indeterminate, and the vaginal chlamydia PCR positive. Further testing is required. You recall Jan to the clinic and she returns, anxious. You explain the HIV screening test result was indeterminate, which could represent a false positive result or early HIV infection.

You collect further serology for repeat testing and supplementary tests: HIV proviral DNA, p24 antigen and western blot. You emphasise that HIV is a treatable, manageable, chronic infection; that current therapy is simple and effective, and that the prognosis is good. Jan is provided with HIV information, online resources and contacts for psychosocial support. You provide her treatment for chlamydia with 1gm azithromycin. You arrange a return visit in one week and advise Jan you will phone her the following day to see how she’s going.

The HIV antibody, proviral DNA and p24 antigen tests are positive, confirming HIV infection. The western blot is indeterminate, however will evolve with time. You relay these results to Jan and discuss the next steps including referral, monitoring and follow-up. You explore Jan’s concerns including ability to work, transmission risks and implications for her children. Jan presents well and explains that since the original indeterminate HIV result and chlamydia diagnosis, she has contacted a specialist HIV counselling service.

She reports that she had been ready for the “worst case scenario” and thanks you for advising her not to disclose in these early stages. She admits concerns about privacy and confidentiality and disclosure, particularly to her children. You discuss the legalities regarding HIV.8

The topic of contact tracing is broached. Jan was divorced two years ago and last had sex with her ex-husband three years ago. Since this time she has had sex with two men – with an old boyfriend three months after her divorce, and with Clive. She has not had an HIV test since antenatal testing for her youngest child who is 14.

Given her recent seroconversion, the most likely source is Clive. Jan consents to contact tracing and provides an email contact for Clive. She is concerned about her confidentiality, despite anonymity, and for this reason, contact tracing is referred to a sexual health clinic, which organises for a UK-based service to contact Clive. Jan states that she wants to start treatment as soon as possible, and referral options are discussed.

Dr Catriona Ooi is clinical services lead and senior staff specialist, Western Sydney Sexual Health Service

References:

1. NSW Ministry of Health. NSW HIV STRATEGY 2016-2020. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/endinghiv/Publications/nsw-hiv-strategy-2016-2020.PDF

2. The Kirby Institute. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia. Annual Surveillance Report 2015. The Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia, Sydney NSW 2052

3. Morpeth SC et al. Time to HIV-1 Seroconversion similar among patients with acute HIV-1 infection; but there are exceptions… Thirteenth Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Denver, poster 389, 2006

4. Experiences of HIV: the seroconversion study final report 2007-2015. Monograph, The Kirby Institute, UNSW Australia, Sydney Australia

5. New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute 2015 www.hivguidelines.org

6. The INSIGHT study group. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptomatic HIV Infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373(9): 795-807.

7. The TEMPRANO ANRS Study Group. A Trial of Early Antiretrovirals and Isoniazid Preventive Therapy in Africa. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015; 373(9): 808-822.

8. ASHM. Guide To Australian HIV Laws And Policies For Healthcare Professionals. http://hivlegal.

ashm.org.au/