Why have we been waiting so long for an effective, reversible male contraceptive?

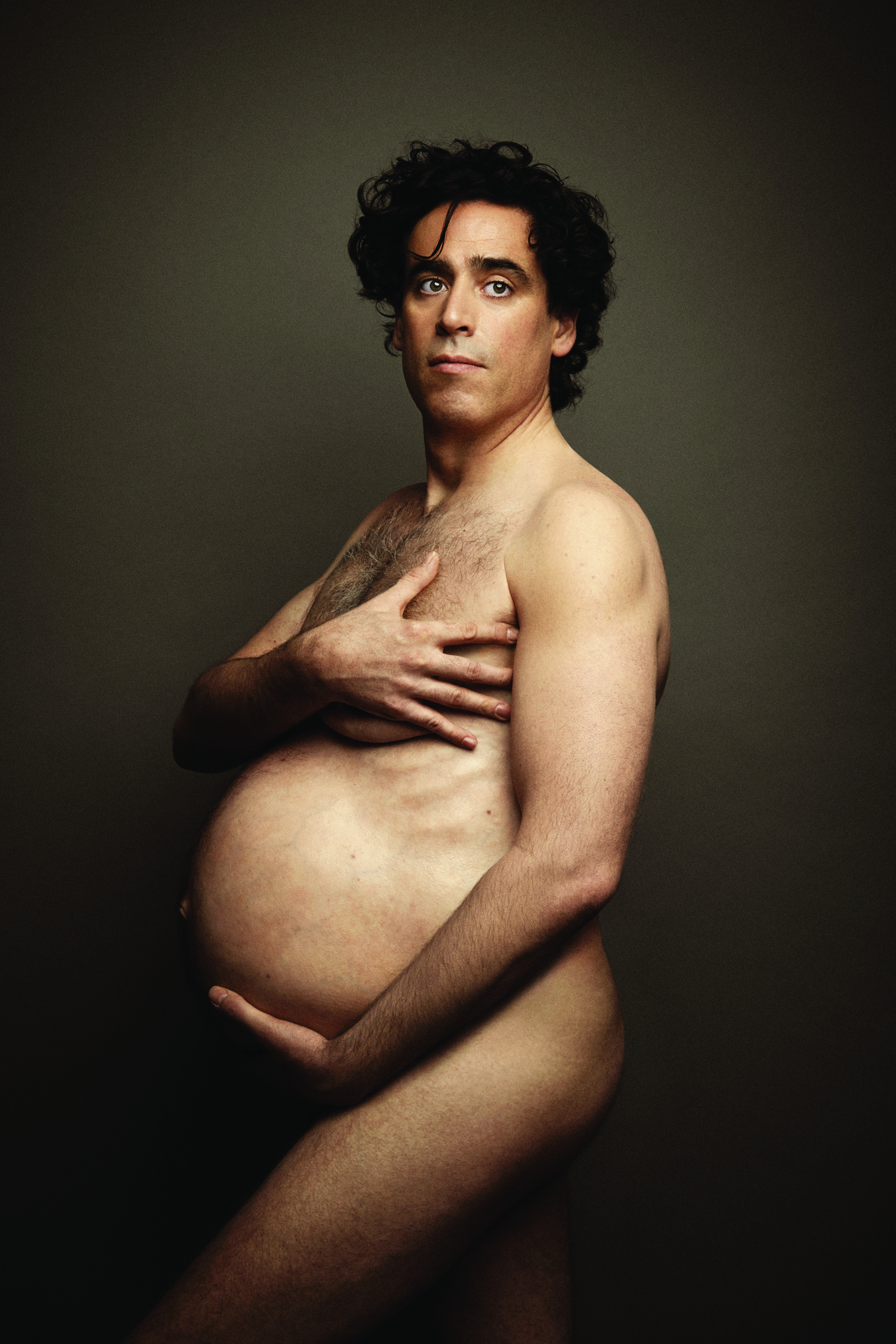

Men and women alike may have been buoyed by a recent landmark study showing an injectable and reversible male contraceptive was on par with female methods, but the reality is that we might be further away from a new male contraception than ever before.

“The joke is that we will have one in five to 10 years, but we’ve been saying that since 1985,” said study author Professor Robert McLachlan, Director of Andrology Australia. “I’m not saying that now.”

Trials into a male hormonal contraception began in the 1970s and have shown the mechanism to be feasible and efficacious.

The new study showed that intramuscular injections of a long-acting progestin and androgen every eight weeks led to almost total suppression of spermatogenesis, which was reversed when the injections were ceased.

Currently, the only contraceptive options available to men are condoms, vasectomy or the withdrawal method, and most men surveyed say they would use a new hormonal contraceptive.

Only a very small number of women say they wouldn’t trust their partner to use it, and two out of three felt that the responsibility of birth control disproportionately fell on women.

The withdrawal method is notoriously ineffective, and the condom has a real-world failure rate of 10-18%, meaning for every 100 women who use condoms, up to 18 may get pregnant each year.

A new reversible method would provide men and their partners with a greater ability to space their children and control over their reproductive destiny, said Professor McLachlan.

His ground-breaking new study showed that a combination of testosterone and norethisterone provided men with the same level of protection from pregnancy as women’s hormonal contraceptives.

Of the 320 men studied across Australia, Germany, Chile, UK, Italy, Indonesia and India, only 4% did not achieve adequate sperm concentration suppression from the injections.

In those that did, there was a failure rate of 1.57 per 100 couples over 56 weeks, and the formulation was as effective at preventing pregnancies in fertile, monogamous couples as female hormonal contraception.

So, the question remains, why have we been waiting so long for a reversible male contraceptive?

Despite the efficacy of the androgen/progestin combination, the study was stopped early due to side effects, such as acne, mood and libido changes, and pain at the injection site.

Some in the media interpreted this as showing an effective male reversible contraception had been found, but men just couldn’t handle the side effects that women have been dealing with for decades.

How it works

Essentially, the male hormonal injection is very similar to the female pill that was developed back in the 50s and 60s.

“You’re using physiological or slightly supraphysiological sex hormone administration to suppress the pituitary and therefore render the testes or the ovary temporarily redundant,” said Professor McLachlan.

Early studies used a high dose of testosterone, which reduced the sperm count in around 60% of the men to zero, and to a very low level in the remainder.

But the high level of testosterone used in these studies meant that many of the men experienced acne and muscle pain, both established side effects of testosterone.

Australia has had a major role in the early studies, with andrologist Professor David Handelsman, head of the ANZAC Research Institute, a driver of the first efficacy study of testosterone in the 1990s.

But an oral contraceptive is completely implausible in men, Professor Handelsman says.

There isn’t a single non-hormonal pill that has ever been developed for women, and if testosterone was given orally, it would either be inactivated by the liver or dangerous if it was chemically modified.

He and Professor McLachlan also helped push the development to the next phase, introducing a progestin into the formulation.

“It does the heavy lifting, suppressing sperm production virtually to zero,” Professor Handelsman said.

But it also suppresses the body’s natural testosterone, meaning that it must be replaced.

And unlike the case with the female pill, it takes around three months – sometimes up to six months – for the sperm machinery to grind down, said Professor McLachlan.

“So there’s quite a lot of lag phase between starting these progesterone and testosterone combinations and it being safe to use as any form of contraception,” he added. “That’s one of the issues.”

The other issue is that not everybody suppresses to a level of less than 1 million/mL, the level thought to provide the same level of contraceptive efficacy as women’s hormonal contraception.

Around 95% of men using the treatment will eventually get to a sperm density of zero or less than a million/mL within six months, so all men need to be checked to make sure they are not one of the 5% for whom it does not work.

And it’s not quite clear why these men don’t respond to the hormonal combination, Professor McLachlan said.

“Some guys are hard to knock down,” he noted.

So unlike women, who for the most part can be given an OCP script and be sure that it’s going to afford a high level of contraception, in men this is an extra hassle.

On a scoreboard in a pharmaceutical company’s HQ, it would be a minus point that 5% of men don’t get to zero, and it’s a minus point that you have to check people after they’ve started taking the drug, Professor McLachlan said.

“You can put up with a little extra hassle, but at the end of the day you’re going to have a whole list of little extras or hassles which cumulatively explains why industry are not interested at the moment,” he said.

Progressively the big companies in the area have all pulled out, with the last one standing, Bayer, removing its funding around the time the most recent study was ceased, Professor McLachlan said.

In short, there’s not of lot of optimism out there about seeing a male hormonal contraceptive on the shelf any time soon.

Side effects

One of the barriers to development is the high demand for safety in products for healthy people.

In Professor Handelsman and Professor McLachlan’s study, almost 1500 side effects were reported, and 61% deemed possibly related to the therapy.

Almost half of the men reported acne, more than one in three reported increased libido and one in six had muscle pain.

One man committed suicide, although it was classified as unrelated to the study.

The effect of the hormonal contraception on mood was also a concern, with 65 reports of emotional disorders in the men.

But because 62 of those 65 reports occurred in the Indonesian centre, all of which were classified as mild, it is possible that the effect was an anomaly.

Some of the confusion about the side effects of this method is due to the study having no control group to compare with.

“For real contraceptive studies you can’t have a placebo,” Professor Handelsman said. “It’s just completely unethical and unacceptable.”

If the mood disturbances were related to the drug combination, one explanation could be that the hormones were unbalanced.

“If the progestin is very effective at suppression, and the testosterone doesn’t last enough, there will be a period of time where they’re unbalanced,” he said, adding that it took decades to work out the optimal balance for the female oral contraceptive.

But in a surprise move, one of the two ethics committees overseeing the study deemed the risks outweighed the potential benefit, and called for a halt to the study.

“We know that many men want to be involved in shared decision making with their partner, and women want men to be involved, but unfortunately all we’ve got to offer at the moment is withdrawal, condoms or vasectomy and that’s it,” said Dr Deborah Bateson, Medical Director at Family Planning NSW. “But it is interesting just to question whether perhaps there are different levels of safety at which the cut-off occurs in for a study men versus a study of women,” she said.

“In 1961 those doses were incredibly high – I mean almost five times the equivalent of the lowest dose pills on the market now, and obviously, that came with much higher, sometimes fatal, risks.

“There was much higher risk of blood clots in those old pills. We’ve refined it enormously,” she said.

Even now, the impact of hormonal contraception on women’s mood has only just been shown convincingly in large randomised trial, finally validating women’s anecdotal experience over decades.

So the science behind a new male hormonal contraception is available, and the technology is now more advanced for men’s contraception than women’s was when it hit the market.

“But the barriers over the past 20 years have just been constraints which have really been social, as well as economic and commercial,” said Dr Bateson.

Because despite the side effects reported in the most recent study, 75% of men who took part in the trial said they’d be willing to use the method again. “I think that’s really significant, and perhaps the side effects were not that bad after all,” she said.

For better or worse, the risk benefit ratio is different now to when the pill was being developed. Now that women’s hormonal contraception is so well finessed, and is so very cheap, it makes the potential money appeal much lower, and the risks in comparison higher.

Why bother risking bringing a new drug to market that will need years to reach the same sophistication as women’s contraception, when there’s something that does the job well enough already?

For Professor McLachlan, the last “flickering ember” of hope for a new male hormonal contraception is a US study of a transdermal combination cream of progestin and testosterone.

“So you might hope that if it goes gang busters then you can do another proof of concept efficacy trial and then they might get a company involved,” he said. “But if you think it’s going to be available in the next five years, I’m telling you you’re dreaming.”

“All of the necessary feasibility, reversibility and acceptability information for male hormonal contraception is far in advance of what was available for hormonal contraceptives in women in the 60s in 70s, but there is no company willing to develop it,” Professor Handelsman said.

“The problem is that over time, not only was there limited pharmaceutical industry interest, but now there’s none.”

With estimates suggesting up to 51% of pregnancies may be unplanned in Australia, the potential market isn’t insignificant.

Estimates have put the global market of a new male contraceptive method at $40 to $200 billion dollars, assuming there are 50 million men interested in the product.

There is public and professional demand, but only industry is capable of developing the product – and no companies are willing to, Professor Handelsman said.

“It’s a classic market failure.”

References:

J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016; online

27 October

Contraception 2016; online 29 June

Hum Reprod 2000; 15(3): 637-645