Parents trying to cope with problem crying in babies are faced with a barrage of conflicting and confusing advice, much of which lacks a sound evidence base

In this second article of our three-part series on crying babies, we explore the impact of interpretative biases on existing evidence concerning the gut and infant cry-fuss behaviours, and offer a neurobiological explanatory model. We also offer integrated, evidence-based management strategies for the baby who cries and fusses when feeding.

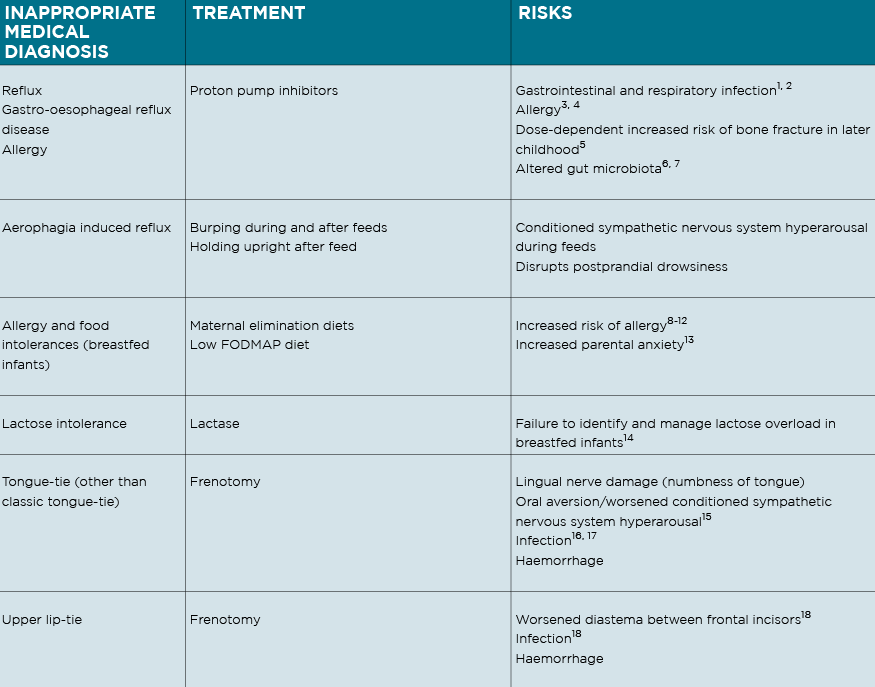

The following signs are commonly inappropriately medicalised in crying babies:

1. Difficulty coming on the breast, back-arching, pulling off, and fussing at the breast, caused by positional instability and breast tissue drag;

2. Excessive flatus, frequent explosive frothy stool, tympanic abdomen and frequent feeding in a breastfed baby, caused by functional lactose overload;

3. Crying and fussing before, during and after feeds either at the breast or bottle, caused by a conditioned sympathetic nervous system (SNS) hyperarousal.

Multiple confounders, in particular the effects of infant-care practices including feeding method on physiology and in particular, the gut, have been and continue to be overlooked in paediatric gastroenterological research.2,3

IS IT REFLUX?

Proton pump inhibitors are no better than placebo,4 and refluxate is close to pH neutral for two hours after a breast or bottle feed. That is, refluxate is not noxious and will not be causing an infant discomfort or pain.5 Frequent reflux events may be associated with cry-fuss problems, but are not causal.

I have argued for almost 20 years, having been immersed in the paediatric gastroenterology research literature, that “reflux” in the crying period was not a disease state that caused oesophagitis and pain, but a benign physiological phenomenon affected by dynamic factors such as high levels of SNS hyperarousal, abdominal pressure, formula feeding, feed spacing, and gastric volume. (Since this unfortunately conflicted with the advice of paediatric gastroenterologists, the Reflux Infants Support Association reported me to AHPRA, claiming I promoted false information which harmed babies!) 2

I also warned, from my knowledge of the research literature, of the increased risk of allergy if we inappropriately treat crying babies with anti-secretory medications or maternal elimination diets, knowledge which is increasingly becoming mainstream. (See table)

COULD IT BE COLIC?

Crying babies have elevated serum pro-inflammatory markers6 and elevated faecal calprotectin regardless of feeding method (though non-crying breastfed babies and younger babies have very high levels of faecal calprotectin, too, compared with formula fed or older babies).7

Gut microbiota changes have been confirmed, in particular increased counts of Escherichia Coli and lower counts of protective Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, in the context of highly variable gut microbiomes in healthy infants.8 A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials demonstrates that breastfed babies with a mean age between 4.4 to 7.1 weeks, who cry and fuss about 4.5 hours a day, will cry and fuss 46 minutes less when taking Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17398.9,10

But this important data is now being interpreted, yet again, through the medicalised lens of linear causality, to conclude that babies cry a lot from gut pain due to colonic inflammation and gas produced by dysbiosis (in the absence of colonic lesions or objective increase in gas).11

The hypothesis that altered pain thresholds due to nocioceptive sensitisation, previously used to justify the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease and treatment in the absence of oesophageal lesions, is now used to explain colonic inflammation and gas pain in the absence of lesions or quantifiably increased gas.

As Associate Professor Joachim Sturmberg, an Australian champion of complexity science in primary care, writes: “The human body does not behave in mechanistic, but rather complex adaptive ways.”12,13 Environmental factors (such as socio-culturally determined approaches to infant care and feeding, and other clinical problems) may result in chronic SNS hyperarousal, but this complexity continues to be ignored in crying baby research. 13

Chronic SNS hyperarousal, or stress, induces low-grade pro-inflammatory states systemically and in the gut of both children and adults, without specifically causing pain – even though the individual may be predisposed, in time, to chronic disease affecting the gut, metabolism, and immune systems.14,15

I am saddened to see the diagnosis of “infant colic” resurgent in the paediatric and paediatric gastroenterology research literature. Overdiagnosis and overtreatment is acknowledged as a rampant international phenomenon,6 and a 2014 analysis proposed that our unchecked compulsion for diagnosis harms infants.17 Medicalised labels for crying babies increase the use of inappropriate medical treatments, with associated risks, and disempower parents.8,19 (See table)

WHAT ABOUT LACTOSE OVERLOAD?

Internationally, crying baby research is characterised by a spectacular, historically constructed omitted variable bias, that of the failure to consider unidentified and unmanaged breastfeeding problems and their complex relationship with unsettled infant behaviour.

This is illustrated in a 2014 analysis of studies cited in two systematic reviews, one on interventions for cry-fuss problems and the other on the efficacy of behavioural approaches to infant sleep zero to six months.20,21

In the paper that reviewed cry-fuss problems, 68 out of 77 studies do not take into account clinical feeding difficulty. In the study concerning first-wave behavioural sleep interventions, none controlled for feeding difficulty, though 20 out of 32 gave recommendations that could make feeding problems worse.22 This omitted variable bias persists throughout crying baby research even though parents report that unsettled infant behaviour is one of the three main reasons they introduce formula (in addition to nipple pain and infant growth concerns).23

To give just one example, none of the studies demonstrating benefit from Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17398 in crying breastfed babies identify and control for lactose overload. Clinically, babies at the severe end of the spectrum of lactose overload cry a lot, and may show signs of excessive flatulence; explosive, frequent, frothy stool (though not always associated with perianal excoriation); tympanic abdomen; very frequent feeding; and rapid weight gain.

The mother may report a very generous milk supply.24,25 This omitted variable bias may explain why Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17398 appears ineffective in formula fed babies.9 Crying breastfed babies with lactose overload, misdiagnosed as allergy, promptly settle when changed to an extensively hydrolysed formula, resulting in confirmation bias.

It is important not to overtreat this spectrum condition, because inappropriate management results in undersupply or mastitis.

Careful education including about the risks, and calibrated return of the baby to one breast over a period of time, for a period of days, increases the proportion of fat ingested with breastfeeds, and slows down gut transit, settling the baby.24,25

Lactase has been demonstrated not to decrease infant crying and is never indicated.26,27 Lactose overload is not a lactose intolerance, and the latter diagnosis is not relevant to crying babies.

RULING OUT ALLERGY

Formula-fed babies may cry less with an extensively hydrolysed formula, although the evidence is weak.27,28 I change a formula-fed crying baby to an extensively hydrolysed formula if all other domains have been addressed without effect, which is rarely the case. In the crying period, the occasional true cow’s milk allergy typically presents as haematochezia, eczema, or urticaria, allergic rhinitis or reactive airways. There is no reliable evidence to suggest that allergy causes crying in breastfed infants.29

WHAT ABOUT FODMAP?

A double blind crossover Australian trial reported decreased crying-fussing durations in 13 breastfed infants on a 10-day maternal low FODMAP diet, but identified no change in faecal pH or calprotectin, no change in lactose or FODMAP composition in breastmilk, no explanatory mechanism, and demonstrated worsened maternal anxiety.30 Dietary elimination should not be recommended for breastfeeding women with crying babies, due to lack of supporting evidence, the risk of worsened anxiety, and increased risk of allergy down the track.27, 31-34 (See table)

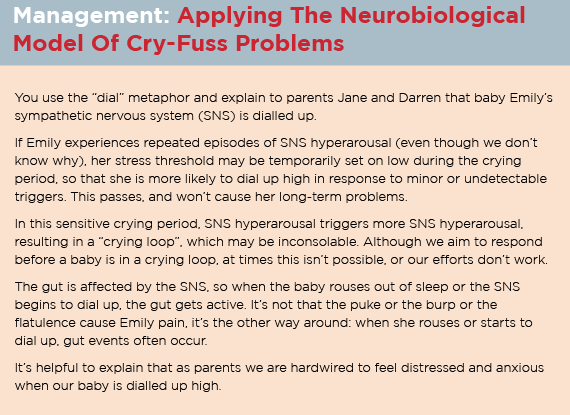

THE NEUROBIOLOGICAL MODEL

The neurobiological model of cry-fuss problems, published in 2013, proposes that infant crying is a complex problem, emerging out of multiple interacting factors –like so much of what we see in general practice – and that simplistic interventions risk unintended outcomes.13, 35

The Neuroprotective Developmental Care (NDC or Possums) five domain approach to crying and fussing is built on the foundations of the neurobiological model of cry-fuss problems.14, 20

An integrated, evidence-based management of the baby who cries and fusses – neuroprotective developmental care or the Possums programs

In the first 100 days, families commonly present with breastfeeding, bottle-feeding, and sleep problems unrelated to crying and fussing. However, the systematic neuroprotective developmental care (NDC) approach to the baby who cries and fusses optimises healthcare delivery by addressing the following five domains:

1. Baby’s health (excluding organic conditions and explaining to parents why popular diagnoses are not relevant);

2. Feeds (breastfeeding and bottle-feeding);

3. Sleep;

4. Baby’s sensory needs; and

5. Maternal mood.

The fussy baby offers, therefore, a window into evidence-based management of the common problems of early life. If you are interested in undertaking upskilling and joining our network, and accessing a range of clinical tools and parent handouts, please consider the NDC Accreditation Pathway.

Existing evaluations of NDC are positive, showing halved crying and fussing, substantially improved maternal mood, and improved sleep.36,37 However, these studies are subject to the same methodological weaknesses and interpretative biases that characterise so much of the research I critique.

There are two important caveats, however. Firstly, NDC is based on unusually rigorously developed, peer reviewed and published systematic reviews and theoretical frames, which analyse and synthesise the extensive and heterogenous research literatures across multiple disciplines. This contrasts with the unconsciously assumed or thinly explicated and discipline-specific theoretical frames that underlie other approaches to infant regulatory problems and clinical breastfeeding interventions. Robust theoretical framing is essential so that the health system invests precious research dollars into programs most likely to succeed.38,39 Secondly, NDC has been successfully delivered in various clinical contexts since 2011, most recently at The Possums Centre, Greenslopes, Brisbane, and is anecdotally highly valued by patients.

A UK study shows that two-thirds of the well-respected NICE guidelines for primary care problems, typically developed out of research by tertiary and university-based experts, lack evidence of efficacy in primary care.40

The principles of the evidence-based medicine movement emphasise that medical research must be developed out of, and relevant to, clinical experience, which, in the case of crying babies, is primary care clinical experience.41

Yet the NHMRC devotes less than 2% of research funding to primary care, and early life care comprises only a tiny part of the broad spread of primary care.

The Medical Research Future Fund lists primary care research among its priorities, but to date, operates predominantly within the “biomedical bubble”.42

Research funding for NDC is, in practice, impossible to attract, due to what could be called “the primary health care innovation trap”.43

FEEDS

Suboptimal fit and hold in breastfeeding

Health professionals have significant training gaps concerning breastfeeding support.44,45

NDC publications first proposed in 2010 that unidentified breastfeeding problems of positional instability and poor milk transfer contributed significantly to unsettled infant behaviour.14, 20, 26, 46 The link between unsettled infant behaviour and breastfeeding difficulty is now acknowledged in breastfeeding research, but erroneously attributed to oral connective tissue ties. 47,48 (See table)

As a result, Medicare-funded frenotomies have increased by 420% between 2006-2016 in Australia. Many, if not most, frenotomies are performed by dentists and not captured by Medicare, and the 3710% increase rate in the Australian Capital Territory, during a time when there were no dentists performing laser frenotomies, may better reflect the national average.49 This exponential increase corresponds to similar increases in North America, in a patterns typical of overtreatment.50,51 Yet frenotomies, in the absence of classic tongue-tie, do not improve breastfeeding outcomes or decrease crying and fussing.52-55 Unfortunately, existing approaches to fit and hold (“latch and positioning”) do not reliably improve breastfeeding outcomes, despite advances in the physiologic initiation of breastfeeding,56-58 and derive from outdated models of the biomechanics of infant suck and swallow.59

Fit and hold problems and positional instability during breastfeeding remain an omitted variable bias in both crying baby research and clinical breastfeeding research.

To give an example, breast massage during breastfeeding disrupts intra-oral breast tissue volumes and risks worsened outcomes, yet is widely advised.5

The NDC gestalt breastfeeding approach has a strong theoretical frame, derived from clinical experience over many years in various clinical contexts, from recent advances in clinical breastfeeding support research, and the latest ultrasound studies of breastfeeding pairs.59,60 It differs from other available approaches in significant ways.

Breastfeeding support practitioners who are upskilled in gestalt breastfeeding do not diagnose posterior tongue-tie or upper lip-tie, or recommend frenotomy for anything other than the rare classic tongue-tie.47, 52

Part three of this series will finalise integrated, evidence-based management of feeding and address management of the baby’s sleep and sensory needs, and maternal mental health.

Dr Pamela Douglas is Medical Director, The Possums Centre, Greenslopes, Brisbane; Associate Professor (Adjunct), Maternity Families and Newborn Centre, MHIQ Griffith University; Senior Lecturer, Discipline of General Practice, The University of Queensland; She is author of The discontented little baby book: all you need to know about feeds, sleep and crying

www.possumsonline.com;

www.pameladouglas.com.au

References:

1. Moore T, Arefadib N, Deery A, West S. The first thousand days: an evidence paper. Parkville, Victoria: Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, 2017.

2. Douglas PS. Excessive crying and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in infants: misalignment of biology and culture. Med Hypotheses. 2005;64:887-898.

3. Chen PL, Soto-Ramirez N, Zhang H, Karmaus W. Association between infant feeding modes and gastroesophageal reflux. Journal of Human Lactation. 2017;1:890334416664711

4. Gieruszczak-Bialek D, Konarska Z, Skorka A, Vandenplas Y, Szajewska H. No effect of proton pump inhibitors on crying and irritability in infants: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Pediatrics. 2015;166:767-770.

5. Orenstein S, Hassall E. Infants and proton pump inhibitors: tribulations, no trials. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45(395-398).

6. Partty A, Kalliomaki M, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Infantile colic is associated with low-grade systematic inflammation. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2017;64(5):691-695.

7. Rhoads JM, Collins J, Fatheree NY, Hashmi SS, Taylor CMea, Luo M, et al. Infant colic represents gut inflammation and dysbiosis. Journal of Pedatrics. 2018;203:55-61.

8. Dubois NE, Gregory KE. Characterizing the intestinal microbiome in infantile colic: findings based on an integrative review of the literature. Biological Research for Nursing. 2016;18:307-315.

9. Sung V, D’Amico F, Cabana MD, Chau K, Koren G, Savino F, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri to treat infant colic: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2017;141(1):e20171811.

10. Dryl R, Szajewska H. Probiotics for management of infantile colic: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Archives of Medical Science. 2018;14(5):1137-1143.

11. Zeevenhooven J, Browne PD, L/Hoir MP, De Weerth C, Benninga MA. Infant colic: mechanisms and management. Nature Reviews: Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2018;15:479-496.

12. Sturmberg J, Topolski S. For every complex problem, there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2014;6:1017-1025.

13. Douglas PS, Hill PS, Brodribb W. The unsettled baby: how complexity science helps. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:793-797.

14. Douglas PS, Hill PS. The crying baby: what approach? Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:523-529.

15. Rohleder N. Stimulation of systemic low-grade inflammation by psychosocial stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2014;76(3):181-189.

16. Brownlee S, Chalkidou K, Doust J, Elshaug AG, Glasziou P, Heath I, et al. Evidence for overuse of medical services around the world. The Lancet. 2017;Published online January 8 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32585-5.

17. Coon ER, Quinonez RA, Moyer VA, Schroeder AR. Overdiagnosis: how our compulsion for diagnosis may be harming children. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):1-11.

18. Scherer L, Zikmund-Fisher B, Fagerlin A, Tarini B. Influence of “GERD” label on parents’ decision to medicate infants with excessive crying and reflux. Pediatrics. 2013;131:1-7.

19. Barr RG. Changing our understanding of infant colic. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(12):1172-1174.

20. Douglas P, Hill P. Managing infants who cry excessively in the first few months of life. BMJ. 2011;343:d7772.

21. Douglas P, Hill PS. Behavioural sleep interventions in the first six months of life do not improve outcomes for mothers or infants: a systematic review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2013;34:497–507.

22. Douglas PS. Poster presentation: Blind spot? Unidentifed feeding problems in infant cry-fuss and sleep research. 12th International Cry-fuss Research Workshop; Warwick, UK, 2014.

23. Odom E, Scanlon K, Perrine C, Grummer-Strawn L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatics. 2013;131:e726-732.

24. Evans K, Evans R, Simmer K. Effect of the method of breastfeeding on breast engorgement, mastitis and infantile colic. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84(8):849-852.

25. Smillie CM, Campbell SH, Iwinski S. Hyperlactation: how ‘left brained’ rules for breastfeeding can wreak havoc with a natural process. Newborn and Infant Nursing Reviews. 2005;5:49-58.

26. Douglas P. Diagnosing gastro-oesophageal reflux disease or lactose intolerance in babies who cry alot in the first few months overlooks feeding problems. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49(4):e252-e256.

27. Gordon M, Biagioli E, Sorrenti M, Lingua C, Moja L, Banks SS, et al. Dietary modifications for infantile colic. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018:doi:10.1002/14651858.CD14601129.pub14651852.

28. Allen KJ, Davidson GP, Day AS, Hill DJ, Kemp As, Peake JE, et al. Management of cow’s milk protein allergy in infants and young children: an expert panel perspective. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45:481-486.

29. Bergmann MM, Caubet J-C, McLin V, Belli D, Schappi M, Eigenmann P. Common colic, gastroesophageal reflux and constipation in infants under 6 months do not necessitate an allergy work-up. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2014:doi: 10.1111/pai.12199.

30. Iacovou M, Craig SS, Yelland GW, Barrett JS, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Randomised clinical trial: reducing the intake of dietary FODMAPS of breastfeeding mothers is associated with a greater improvement of the symptoms of infantile colic than for a typical diet. Alimentary Pharmacological Therapies.48(10):doi:10.1111/apt.15007.

31. Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, Groome A. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease. JAMA. 2016;316:doi:10.1001/jaja.2016.12623.

32. Joneja JM. Infant food allergy: where are we now? Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2012;36:49S.

33. Longo G, Berti I, Burks AW, Krauss B, Barbi E. IgE-mediated food allergy in children. Lancet. 2013;382:1656-1664.

34. Muraro A, Halken S, Arshad SH, Beyer K, Dubois AEJ, Du Toit G, et al. EEACI Food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines. Primary prevention of food allergy. Allergy 2014;69:590-601.

35. Douglas PS, Hill PS. A neurobiological model for cry-fuss problems in the first three to four months of life. Med Hypotheses. 2013;81:816-822.

36. Ball H, Douglas PS, Whittingham K, Kulasinghe K, Hill PS. The Possums Infant Sleep Program: parents’ perspectives on a novel parent-infant sleep intervention in Australia. Sleep Health. 2018;4(6):519-526.

37. Douglas P, Miller Y, Bucetti A, Hill PS, Creedy D. Preliminary evaluation of a primary care intervention for cry-fuss behaviours in the first three to four months of life (“The Possums Approach”): effects on cry-fuss behaviours and maternal mood. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2013;21:38-45.

38. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Mitchie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:979-983.

39. Fox A, Gardner G, Osborne S. A theoretical framework to support research of health service innovation. Australian health review: a publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 2014:doi.org/10.1071/AH1403.

40. Steel N, Abdelhamid A, Stokes T. A review of clinical practice guidelines found that they were often based on evidence of uncertain relevance to primary care patients. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;67(11):1251-1257.

41. Greenhalgh T. Evidence-based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ. 2014;348.

42. Doggett J. The ‘Biomedical Bubble’ and the future of the Medical Research Future Fund. Croakey. 2018;11 August 2018:https://croakey.org/the-bio-medical-bubble-and-the-future-of-the-medical-research-future-fund/.

43. Winzenberg TM, Gill GF. Prioritising general practice research. Medical Journal of Australia. 2016;205:529.

44. Renfrew M, Pokhrel S, Quigley M, McCormick F, Fox-Rushby J, Dodds R, et al. Preventing disease and saving resources: the potential contribution of increasing breastfeeding rates in the UK. London: Unicef UK; 2012.

45. Gavine A, MacGillivray S, Renfew MJ, Siebelt L, Haggi H, McFadden A. Education and training of healthcare staff in the knowledge, attitudes and skills needed to work effectively with breastfeeding women: a systematic review. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2017;12(6):DOI 10.1186/s13006-13016-10097-13002.

46. Douglas P, Hiscock H. The unsettled baby: crying out for an integrated, multidisciplinary, primary care intervention. Med J Aust. 2010;193:533-536.

47. Douglas PS. Untangling the tongue-tie epidemic. Medical Republic. 2017;1 September:http://medicalrepublic.com.au/untangling-tongue-tie-epidemic/10813.

48. Ghaheri BA, Cole M, Fausel S, Chuop M, Mace JC. Breastfeeding improvement following tongue-tie and lip-tie release: a prospective cohort study. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:1217–1223.

49. Kapoor V, Douglas PS, Hill PS, Walsh L, Tennant M. Frenotomy for tongue-tie in Australian children (2006-2016): an increasing problem. MJA. 2018:88-89.

50. Walsh J, Links A, Boss E, Tunkel D. Ankyloglossia and lingual frenotomy: national trends in inpatient diagnosis and management in the United States, 1997-2012. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 2017;156(4):735-740.

51. Joseph KS, Kinniburg B, Metcalfe A, Raza N, Sabr Y, Lisonkova S. Temporal trends in ankyloglossia and frenotomy in British Columbia, Canada, 2004-2013: a population-based study. CMAJ Open. 2016;4:e33-e40.

52. Douglas PS, Cameron A, Cichero J, Geddes DT, Hill PS, Kapoor V, et al. Australian Collaboration for Infant Oral Research (ACIOR) Position Statement 1: Upper lip-tie, buccal ties, and the role of frenotomy in infants Australasian Dental Practice. 2018;Jan/Feb 144-146.

53. Douglas PS. Making sense of studies which claim benefits of frenotomy in the absence of classic tongue-tie Journal of Human Lactation. 2017;33(3):519–523.

54. Power R, Murphy J. Tongue-tie and frenotomy in infants with breastfeeding difficulties: achieving a balance. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2015;100:489-494.

55. O’Shea JE, Foster JP, O’Donnell CPF, Breathnach D, Jacobs SE, Todd DA, et al. Frenotomy for tongue-tie in newborn infants (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(3):Art. No.:CD011065.

56. Schafer R, Watson Genna C. Physiologic breastfeeding: a contemporary approach to breastfeeding initiation. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2015;60:546-553.

57. Woods N, K, Woods NF, Blackburn ST, Sanders EA. Interventions that enhance breastfeeding initiation, duration and exclusivity: a systematic review. MCN. 2016;41(5):299-307.

58. Svensson KE, Velandia M, Matthiesen A-ST, Welles-Nystrom BL, Widstrom A-ME. Effects of mother-infant skin-to-skin contact on severe latch-on problems in older infants: a randomized trial. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2013;8:1.

59. Douglas PS, Geddes DB. Practice-based interpretation of ultrasound studies leads the way to less pharmaceutical and surgical intervention for breastfeeding babies and more effective clinical support. Midwifery. 2018;58:145–155.

60. Douglas PS, Keogh R. Gestalt breastfeeding: helping mothers and infants optimise positional stability and intra-oral breast tissue volume for effective, pain-free milk transfer. Journal of Human Lactation. 2017;33(3):509–518.

Table references

1. Freedberg DE, Lamouse-Smith ES, Lightdale JR, Jin Z, X YY, Abrams JA. Use of acid suppression medication is associated with risk for C. difficile infection in infants and children: a population-based study. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;61:912-917.

2. Orenstein S, Hassall E, Furmaga-Jablonksa W, Atkinson S, Raanan M. Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole in infants with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Journal of Pedatrics. 2009;154:514-520.

3. Mitre E, Susi A, Kropp LE, Schwartz DJ, Gorman GH, Nylund CM. Association between use of acid-suppressive medications and antibiotics during infancy and allergic diseases in early childhood. JAMA Pediatrics. 2018:doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0315.

4. Trikha A, Baillargeon J, Kuo Y, Tan A, Pierson K, Sharma G, et al. Development of food allergies in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease treated with gastric acid suppressive medications. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2013;24:582-588.

5. Malchodi L, Wagner K, Susi A, Gorman GH, Hisle-Gorman E. Early antacid exposure increases frature risk in young children. Pediatics. 2018;142(1).

6. Jackson MA, Goodrich JK, Maxan M-E, Freedberg DE, Abams JA, Poole AC, et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. BMJ. 2016;65:749-756.

7. Clooney AG, Bernstein CN, Leslie WD, Vagianos K, Sargent M, Laserna-Mendieta EJ, et al. A comparison of the gut microbiome between long-term users and non-users of proton pump inhibitors. Alimentary Pharmacological Therapies. 2016;43:doi:10.1111/apt.13568.

8. Ierodiakonou D, Garcia-Larsen V, Logan A, Groome A. Timing of allergenic food introduction to the infant diet and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease. JAMA. 2016;316:doi:10.1001/jaja.2016.12623.

9. Muraro A, Halken S, Arshad SH, Beyer K, Dubois AEJ, Du Toit G, et al. EEACI Food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines. Primary prevention of food allergy. Allergy 2014;69:590-601.

10. Gordon M, Biagioli E, Sorrenti M, Lingua C, Moja L, Banks SS, et al. Dietary modifications for infantile colic. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018:doi:10.1002/14651858.CD14601129.pub14651852.

11. Joneja JM. Infant food allergy: where are we now? Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2012;36:49S.

12. Longo G, Berti I, Burks AW, Krauss B, Barbi E. IgE-mediated food allergy in children. Lancet. 2013;382:1656-1664.

13. Iacovou M, Craig SS, Yelland GW, Barrett JS, Gibson PR, Muir JG. Randomised clinical trial: reducing the intake of dietary FODMAPS of breastfeeding mothers is associated with a greater improvement of the symptoms of infantile colic than for a typical diet. Alimentary Pharmacological Therapies.48(10):doi:10.1111/apt.15007.

14. Douglas P. Diagnosing gastro-oesophageal reflux disease or lactose intolerance in babies who cry alot in the first few months overlooks feeding problems. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49(4):e252-e256.

15. Wattis L, Kam R, Douglas PS. Three experienced lactation consultants reflect on the oral ties phenomenon. Breastfeeding Review 2017;25(1):9-15.

16. Reid N, Rajput N. Acute feed refusal followed by Staphylococcus aureus wound infection after tongue-tie release. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2014;50:1030-1031.

17. Maciag M, Sediva I, Alexander-Scott N. Submandibular swelling and fever following fenulectomy in a 13-day-old infant. Clinical Pediatrics (Phil). 2016;55(10):990-992.

18. Douglas PS, Cameron A, Cichero J, Geddes DT, Hill PS, Kapoor V, et al. Australian Collaboration for Infant Oral Research (ACIOR) Position Statement 1: Upper lip-tie, buccal ties, and the role of frenotomy in infants Australasian Dental Practice. 2018;Jan/Feb 144-146.