The cutout anatomic sheets Vesalius published as a teaching resource have been reproduced in full for the first time.

Andreas Vesalius had a lot of guts.

You’d have to, to teach human anatomy in 16th-century Europe using cadaver dissection when the Catholic Church frowned on the practice and when the establishment still relied on the antique and inaccurate teachings of Galen, who had only cut up monkeys.

Vesalius had a passion from a young age, cutting up small animals and, in his student days, raiding graveyards for fresh corpses. A bold and precocious student, he was given the chair of medicine at Padua the day he graduated, just in case any academic readers are feeling a bit under-achievy today.

As well as his very popular real-time dissection sessions for students, he made full use of printing technology to spread his findings (he complained about having his work stolen and distributed in inferior versions).

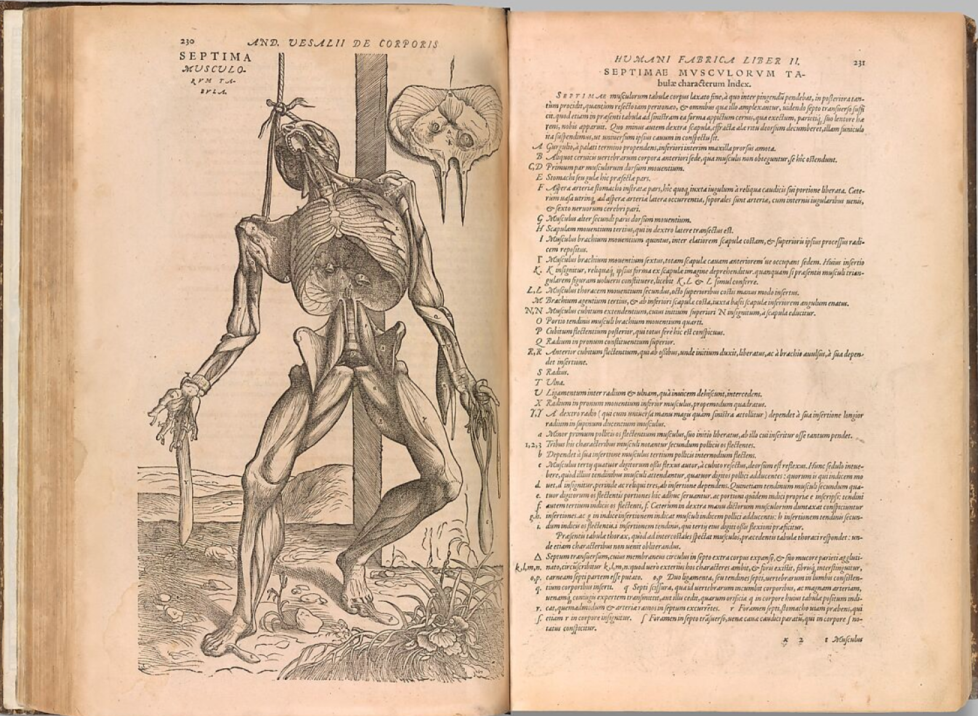

The woodcuts in his major 1543 work De humani corporis fabrica and the Epitome that followed, usually attributed to Jan Steven van Calcar, are dramatic and beautifully detailed:

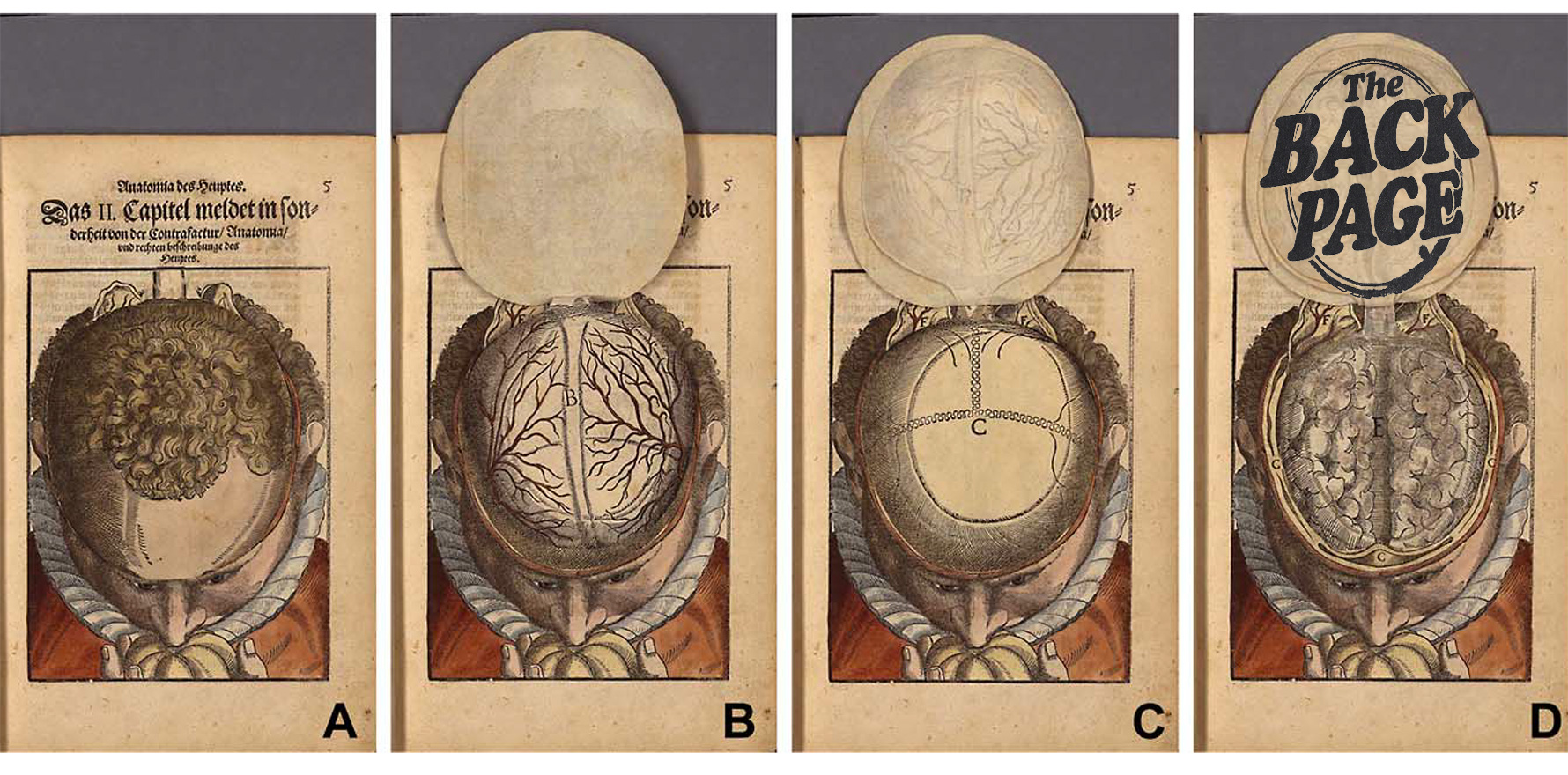

But he also used a new format developed only a few years before called fugitive anatomic sheets, in which layered flaps of paper allowed the student to see the human anatomy at various levels of organs. The owner of the book would first have to cut out the pieces and paste them together into manikins, which worked as a dissection guide or in place of dissection.

“Each layer image of the manikin could be removed or flipped up or down to reveal the underlying or overlying structures, mirroring the actual process of dissecting a human cadaver,” write the authors of a paper in Neurosurgery in which these rare manikins are reproduced for what is surprisingly the first time.

“By acquiring a copy of Epitome, students gained access to a resource that offered the most accurate representation of the human body for the period, enabling them to conduct dissections independently without requiring an instructor’s direct guidance.”

As for Vesalius, he probably should have stuck to teaching, in which he became something of a celebrity. Instead he accepted a job as court physician in the far more conservative Spain under Emperor Charles V and later his son Philip, where he appears to have been miserable – partly because he wasn’t allowed to dissect so much as a mouse.

When he finally escaped this tenure it was to undertake a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, after which he planned to return to the professorship at Padua where he had spent the best years of his career.

He was once thought to have undertaken this pilgrimage as the price of his life, having been condemned to death by the Inquisition for performing an autopsy on a Spanish noble whose heart was still beating … but that has been dismissed by modern biographers as slander. Pity – great story.

In either case he never made it back, dying suddenly on the island of Zakynthos, where his Venetian ship landed after weeks wandering in the Mediterranean, having been blown off course by bad weather.

He has been plausibly hypothesised to have died of scurvy, a disease thought to have killed two million sailors in two centuries of grand sea exploration. Galen knew what scurvy was but advised avoiding fruit – whoops – and it would be a long time before medical heads could get themselves around the concept of dietary deficiency, a discovery out of reach even for Vesalius.

Send cut-and-paste story tips to penny@medicalrepublic.com.au.