GPs are unconvinced a new online health resource will provide much real benefit

We all know patients turn to the internet first for information and advice when they are feeling unwell, and that often the quality of the search results can be dubious.

So an initiative by internet search giant Google to improve the standard of search results for people seeking health information should be good thing, surely?

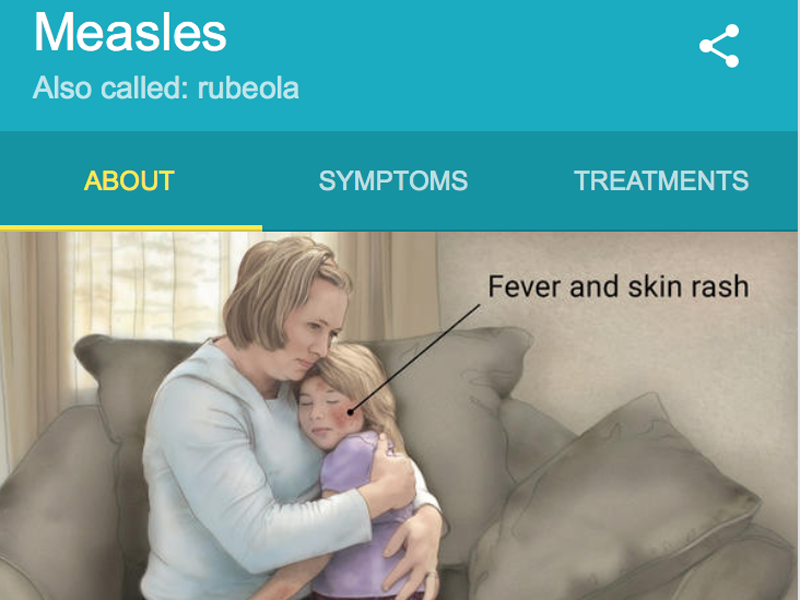

Called Google Health Cards, and launched in Australia this month, typing in a health condition into the search engine now produces a custom-made card with information on symptoms, treatments and prevalence.

But GPs are unconvinced the new system will provide much benefit to patients.

While more accurate information was welcome, there were risks associated with patients Googling their symptoms instead of consulting a GP, medical associations have warned.

Dr Nathan Pinskier, the chair eHealth & Practice Systems at RACGP, said there was limited academic evidence of how online tools could help patients.

“The College’s view is that, provided [online information] is integrated as part of the care pathway and people continue to see their regular health provider and GP, that’s good,” he said. “But if it creates risks that have yet to be identified, then we need to know about those.”

A quick Google search could help allay a patient’s fears, he said. But it could also have the opposite effect by increasing anxiety.

The Google Health Cards have a disclaimer at the bottom, which reads: “Consult a doctor for medical advice”. However, people often did not read cautions, said Dr Pinskier.

Dr Tony Bartone, the vice president of the Australian Medical Association, said Health Cards were a “long-overdue improvement” but cautioned against a “cookie cutter approach to self-diagnosis”.

“There’s nothing wrong with people wanting information, as long as … it’s not used to try and assist in a short cut,” he said.

Another criticism was that the cards were too simplistic to be particularly useful.

“The information is of general nature and fairly basic,” said Dr Lina Safro, a GP and medical education coordinator at Family Planning NSW. “It’s hard to imagine a GP printing the card and handing it to a patient as a Fact Sheet at the end of the consultation, which is one of the stated aims of Google cards.”

Dr Safro said there were other equally reliable, evidence-based online resources available through government websites.

Google has gone to some lengths to fact-check the Health Cards, but GPs remain sceptical about the company’s motivations.

The project team – led by cardiologist and Google employee Dr Kapil Parakh – were careful to pass every fact by a team of at least 10 medical doctors at Google and the Mayo Clinic for accuracy.

The team also stressed that the cards, which were initially launched in the US in 2015 and have been adapted for the Australian context, were not medical advice.

“All of the gathered facts represent real-life clinical knowledge,” Google project manager Dr Isobel Solaqua wrote in a blog post.

Pharmaceutical companies do not sponsor the Health Cards and the cards do not name any medicines. But GPs are taking Google’s claims of independence with a grain of salt.

“You always have to be quizzical,” said Dr Pinskier. “If it stays independent, that’s great. But at the end of the day [Google] is out there to make dollars, isn’t it?”

Dr Safro said she would like to know Google’s motivation for creating the cards. “Google is a business, therefore it’s reasonable to presume that the motivation for the project is commercial,” she said.

Google did not respond to questions from The Medical Republic.