Current approaches to preventing illegal drug use clearly are not working. So why can’t we have a rational debate about law reform?

Sir Nicholas Clegg remembers something strange about his time in the UK government. From 2010, when he became deputy prime minister under David Cameron, Sir Nicholas began to speak with his fellow MPs about the country’s approach to illegal drugs and noticed an alarming disconnect between science and politics, evidence and emotion.

“When I spoke privately to my then-colleagues in the government that Cameron and I had formed, I couldn’t find a single minister that did not agree with me that what we were doing with drugs was deeply irrational,” he says.

That is, after decades of a “war on drugs”, those fighting against the drugs weren’t winning. There was accumulating evidence showing that trying to tackle a social, psychological and environmental problem primarily with a criminal justice approach was not getting anyone anywhere.

“But then they would go on to say: ‘We can’t possibly do anything about it’.”

The ministers would point to other more pressing problems, or accurately point out that the newspapers and public would be alarmed by the prospect of deviating from the current policy approach to illegal drugs and drug use.

It is impossible to exaggerate how fear, an almost atavistic, primal fear, will lead voters to support policies which the politicians that represent them know would not help those voters, and in many cases cause more harm, Sir Nicholas says.

Since then, the former Liberal Democrat leader has joined the likes of businessman Sir Richard Branson and former UN general secretary Kofi Annan in the Global Commission on Drug Policy, a group dedicated to making drug policies more evidence-based, and more health and human rights oriented.

The commission represents a view that is becoming increasingly mainstream: that the current hardline prohibition approach to drugs has sacrificed the wellbeing of individuals and communities for the sake of trying to create a drug-free world. Not only has it failed at that goal, but the aggressive crusade has left a trail of destruction in its wake, they argue.

It’s true that some countries and states are coming up with creative responses to drugs that no longer lean on law enforcement as the major tool.

The United States and Canada have been some of the most prominent in their about-face on decriminalising and legalising marijuana, but other countries, such as Portugal and the Czech Republic, have taken an even more bold step by decriminalising all drug use and personal possession, whether it was marijuana or cocaine and heroin.

And it seems to have paid off. Drug-induced deaths in those countries are among the lowest in any European country, and the fear of a flood of drug-tourists or eager locals using more drugs has not been realised.

In March next year, the UN member states will meet again to set out the global drug policy for the next decade.

Speaking at several sessions at the EuroScience Open Forum in Toulouse last month, a number of advocates on drug policy reform joined Sir Nicholas in calling for an end to the war on drugs and a more evidence-based approach to improving the lives of people affected by drugs.

A powerful sign of that would be for the UN to take into account all that has been learned over the last few decades about illegal drug use and the attempts to prevent that use, and more clearly prioritise the health and wellbeing of individuals.

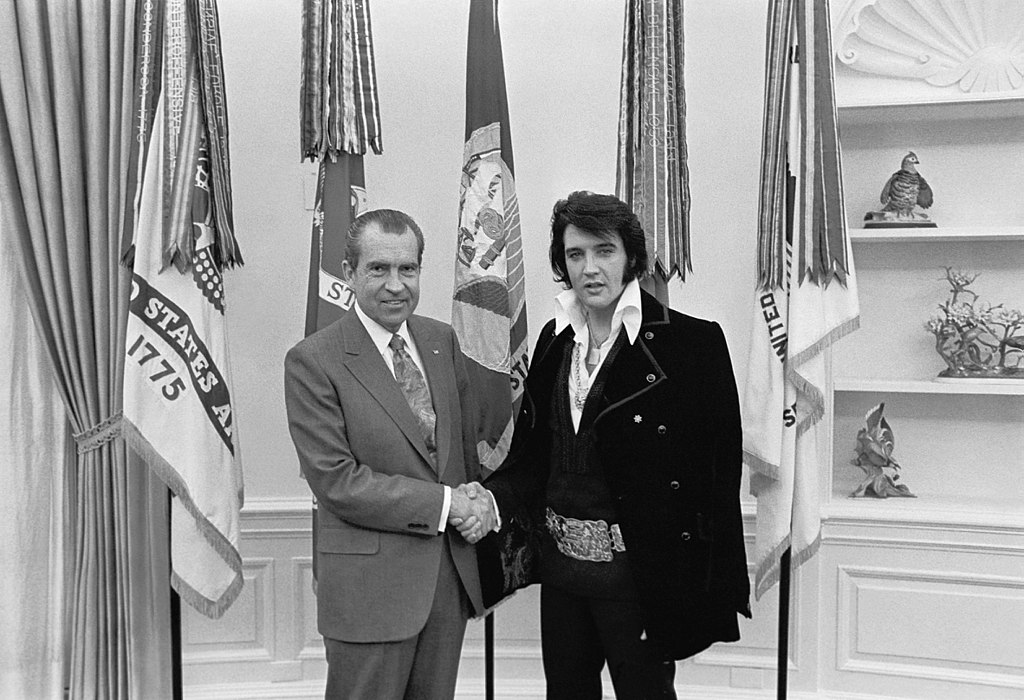

The war on drugs has been waging on for half a century, since former US president Richard Nixon declared drug abuse “public enemy number one”.

The “war” has resulted in mass incarceration of those involved in the use, manufacture and trade of drugs, the destabilisation and corruption of countries across the world and an intense demonisation of drug users.

But where you have one of the most aggressive countries, the United States, softening its stance and allowing states to legalise marijuana, more conservative countries are pushing the other way.

Right now, Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte is enthusiastically backing extrajudicial killings for drug addicts and dealers. China and Thailand both still apply the death penalty for drug-related offences. Russia has been particularly vocal about its adherence to a zero tolerance approach, echoing sentiments across Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

THE RUSSIAN STORY

Anya Sarang, president of the Andrey Rylkov Foundation for Health and Social Justice in Moscow, paints a bleak picture of the damage done in her country by such an extreme approach.

“We now experience a health crisis,” she says. Russia has the fastest growing HIV epidemic outside of sub-saharan Africa and Nigeria, and accounts for two in three cases of HIV in Europe.

Each hour that passes in Russia brings with it 10 new HIV cases, amounting to more than 100,000 registered cases each year. And in the midst of that, almost 32,000 die of AIDS, “in a year when HIV treatment should be available to everyone”.

The reasons for this health crisis are that most of the HIV infections are among people who inject drugs, primarily opioids. Meanwhile, the government refuses to support prevention programs and often withholds HIV treatment for people injecting drugs.

Opioid-substitution treatments are illegal in Russia, harm-reduction programs, such as needle syringe programs and informational campaigns, are opposed by the state and considered a threat to the national drug strategy, despite being strongly supported by research.

“So instead of health control, we have police terror,” Ms Sarang says.

She called police violence towards drug users “omnipresent, routine and normalised”. This includes arbitrary detention, physical violence, extortion of money, rape (particularly of sex workers), and torture to extort confessions.

Individuals have been denied methadone or other drug-dependence treatment, as well as HIV medications, while in police custody to force abstinence or obtain a confession.

In an approach that she says grows out of the “Soviet repressive psychiatry”, drug users are often seeking help from rehab centres in the private sphere, which offer outdated and ineffective treatments such as flogging, starvation, electroshock therapy and electrodes placed in the patients’ ears.

While these methods have no evidence to support them, strategies that have a strong evidence base are banned. For trying to promote harm-reduction measures and access to opioid substitution treatments such as methadone and buprenorphine, Ms Sarang’s NGO was branded as a foreign agent and accused of engaging in political activity.

“It is one extreme example of how the repressive approach to drug policy can harm millions of people living in the country and impede access to health and violate human rights,” Ms Sarang says.

“This position is based on outdated idealistic rhetoric of a drug-free world, to be achieved by zero tolerance to drug use.”

While it would seem increasingly hard to believe that a law-enforcement approach would achieve these goals, unfortunately the international treaties are still cited by Russia and other countries to justify their tactics.

On the other hand, sometimes a crisis is what’s needed to force politicians to look at the evidence.

America’s opioid epidemic finally did that in rural Indiana, where a HIV outbreak bloomed amid citizens who had become hooked on prescription opioids and then been forced into injecting to feed their addiction.

But then-governor Mike Pence (now vice president) initially opposed needle exchanges and supported the law against them as an anti-drug measure. But soon it became impossible to ignore that the hundreds of new cases of HIV were a result of needle sharing, and the governor allowed a temporary exemption to the law against needle sharing, then later removing it altogether.

Similarly, Canada, Sweden and Denmark have begun allowing drug-consumption rooms and take-home medicine programs. So maybe another crisis is going to be what we rely on to shift the discussion away from fear-based rhetoric to something that reflects what research shows will help.

Another member of the Global Commission on Drug Policy joining Sir Nicholas is Professor Michel Kazatchkine, a leading immunologist who has spent decades fighting HIV/AIDs, who now sees the current global approach to drug prohibition as a major driver of such problems.

CLOSING THE EVIDENCE GAP

The French physician and the former politician have both called on people from all facets of society to demand a closing of the gap between evidence and policy.

“As a physician and former scientist, I must say I cannot think of any other area of medicine or social sciences where the gap between what the evidence tells us we should do, and the policies, is so great,” Professor Kazatchkine says.

“That gap has killed millions of people and generated a huge amount of unnecessary and avoidable suffering for people and communities around the world.”

These policies are founded on the “misguided hope” that illicit markets will be extinguished using harsh tactics such as imprisonment and destroying crops to deter people from consuming and producing drugs, he says.

“But in fact what happens is more and more people consume drugs worldwide.”

Each year, hundreds of millions of people across the world use illicit substances, some for enjoyment, some to relieve pain and some for cultural reasons.

In fact, despite the aggressive pursuit of a drug-free world, our hunger for illicit drugs has only grown. The last 10 years has seen a 33% increase in the number of people aged 15 to 64 who have taken illegal drugs, now sitting at 247 million.

At the same time, more drugs are being produced every year. Last year, the opium cultivation in Afghanistan reached record highs, almost doubling from the year before. Colombia saw similar all-time highs in coca production last year, and new psychoactive substances are developed daily.

The war is not being won.

And the impacts of this are far and wide. From overcrowded prisons to ballooning death rates.

A prohibition approach has generated a huge black market, with some estimates saying it accounts for about one third of the entire $426 billion to $652 billion global black market.

Such vast sums of money go hand-in-hand with corruption, threatening democracies and leading to what are essentially narcostates in some countries, Professor Kazatchkine says.

In Mexico, more than 160,000 have died violently since the beginning of the war on drugs.

A 2013 report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime found that drug possession accounted for four in five instances of global drug-related offences. And when individuals are jailed for more serious crimes such as trafficking, it’s more often the low level traffickers rather than the kingpins.

As in the alcohol prohibition era in the United States, where the market shifted towards harder drinks with a higher percentage of alcohol, so too does the illegal market create pressure on manufacturers to create higher potency substances to reduce the volume, and hence risks, for traffickers.

The increasing potency of marijuana is one area in which this has become a concern, and carfentanyl could be seen as the inevitable endpoint. What could be more alluring than a substance which is 100 times more potent than fentanyl, which itself is 100 times stronger than morphine? It makes much more sense to opt for the smallest package possible when trafficking across state or country lines.

Unsurprisingly, the numbers of people dying from opioid-related overdoses is skyrocketing, particularly in North America.

Those in favour of regulation argue that the most stupid thing to do would be to leave the manufacture of such potentially dangerous substances in the hands of criminal gangs, arguing that the government has a much stronger place to work from in either manufacturing or regulating the manufacture of them,such as occurs with alcohol, tobacco and prescription medicines.

What is being done to prevent these deaths? Well society has a number of tools at its disposal. Safe-injecting rooms, needle-exchange programs, opioid-substitution therapies such as methadone and buprenorphine, wider availability of naloxone and good samaritan laws have all been shown to help reduce harms and save lives.

Some countries are introducing some of these and others are disregarding them altogether.

US President Donald Trump has approached the issue of opioid overdoses by suggesting tougher law enforcement, despite evidence repeatedly showing it is an ineffective route to take.

To explore this very topic, the UK government commissioned an evaluation of 11 different countries and found there was no “obvious relationship between the toughness of a country’s enforcement against drug possession, and levels of drug use in that country”.

One thing that criminalising drug use does especially well is creating an environment of fear of arrest and punishment that stigmatise users and make it harder for people to seek help.

Alongside destabilisation and corruption within countries themselves, the war on drugs has led to the an escalation in law enforcement and militarisation of law enforcement. A heavy-handed approach to drugs is also used as a tool of social control.

The hunger to arrest people disrupts individual lives and communities. Globally, one in five people in prison are incarcerated because of a drug office, but in Europe, four in five of these are arrests for possession and personal use.

That arrest isn’t just a matter of cost and time for the individual, criminal records go on to prevent people from getting jobs, take mothers away from their children and burden the criminal justice system that could better funnel that money into preventing violent crimes or tackling the drug dealers higher up the chain.

EXPERIMENTING WITH REGULATION

Laurene Collard, from the French health professional network Federation Addiction, argues it is vital to start discussing new drug regulation options as soon as possible.

While she supports decriminalisation of drug use, “We don’t expect every problem to disappear with decriminalisation”.

“Our main issue is that if you have a cure that doesn’t work, a policy that can’t even be applied correctly, shouldn’t we try to find a new one?”

The irony is our hypocrisy to the illicit drugs and the licit ones. Ms Collard recalls being asked to present on two different debates in a recent French national assembly. In the first, when they presented evidence in favour of drug-consumption rooms, they were accused by some MPs of spinning drug use in a positive light, and having abandoned the struggle against drugs.

“As it happens, on the next morning we had a hearing in front of the very same MPs regarding the regulation of tobacco and alcohol. There we promoted regulation practices and restrictions to access to these substances,” she says.

The very same MPs countered that such restrictions would contradict individual liberties and prohibit the profitability of the manufacturers.

Ms Collard points to the disconnect that in France drug-consumption rooms operate within rigid conditions and are up for evaluation after a six-year period. On the other hand, alcohol kills three million or more each year around the world, and yet billboards for the substance are commonly seen plastered around public areas.

Not all regulation is the same though. For example, with marijuana use, the US has opted for a more market-driven approach compared with a country such as Uruguay, which oversees the market by controlling the amount of marijuana citizens are allowed to buy each month, the potency and strains.

And the risks posed by the legalisation of currently illegal drugs cannot be lightly dismissed. As societies have seen with troubling examples in the tobacco and alcohol industry, not to mention prescription opioids, such moves wouldn’t come without harms.

The opioid epidemic in the US is a good example of regulation failing to protect people.

Pharmaceutical companies misled patients and doctors, providing free, heavy duty addictive substances to individuals without a legitimate indication, paying doctors to encourage greater prescribing.

As a result, more people in the United States die from opioid overdose deaths today than they do in car accidents, an estimated 42,000 death a year.

So working out the nuts and bolts of regulation is challenging.

Portugal led the way two decades ago when it decriminalised the consumption, purchase and possession of narcotic and psychotropic drugs for personal use. This left the trafficking of drugs still squarely in the realm of punishable.

And because the Portuguese didn’t go so far as to legalise drug use, users who are caught may still face a fine and have to present before a committee tasked with preventing addiction.The committee may recommend medical treatment if the user has a problem with addiction, but the individual is not compelled to act on their recommendations.

The approach has been heralded as a success. Since the new framework was introduced, drug use has dropped, HIV and AIDS rates in users have dropped, and the fears that the country would turn into a drug tourism hotspot did not eventuate.

However, drug users in Portugal still rely on illicit markets for their drugs, which comes with all the problems on purity and funnelling money to unsavory characters.

Other countries, such as Uruguay, Canada and some states in the US, have moved that next step to fully regulate markets such as marijuana to ensure they have control over the whole chain, from cultivation to consumption.

This was always an easier sell for a “soft” drug such as marijuana, but until recently would’ve seemed almost unimaginable for something such as heroin.

Perhaps the opioid epidemic has changed the playing field a little though.

It is no longer possible to ignore the fact that drugs have been with us since the dawn of time and the goal of a drug-free world is unrealistic.

After so many decades, it’s worth asking ourselves what we’re really striving for: a world without drugs?

Or a world with healthier people?