The burden of mental health care is falling on female GPs, leaving them drained and out of pocket. Here’s how that can change.

There is an old English fable that describes a period of drought.

In the midst of famine, a mysterious lady arrives leading a giant cow. She instructs the villagers that the cow will fill any pail, no matter the size, with milk. Only one bucket per home can be filled each day and each bucket must then be carried away, unaided, by the person who had brought it up the hill.

The cow is able to provide a seemingly limitless supply of milk, one pail at a time, until one day when someone brings an unfillable bucket, full of holes and sits down to milk the cow. The milk gushed into the bucket but ran away through the holes. As the last milk is drained, the cow’s hide has become dull, clinging to the curves of her famished ribs. In great distress, the maddened cow runs far away, over the hills, and is never seen again.

Many of our patients find mental health care inaccessible and unaffordable. There is a deep and growing shortage of psychiatrists, and allied health cover is patchy.

Increasingly, the mental health burden of care is shifting on to general practice. Female GPs carry a disproportionate load of mental health care, and the rate of burnout and mental illness in this group is high. This goes twice over for rural areas.

The stories from female GPs commonly contain this sort of comment: “Patients will come to see me and say ‘I usually see Dr Michael/Dr Jarrod/Dr John, for simple things, but I don’t want to waste his time with my mental health, so I’ve come to you.’”

We can talk about individual boundaries, the ability to say no, the capacity to insist on a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work. We can also discuss why the stigma is so high with mental health that patients feel they need to apologise for “bothering” us with their concerns.

However, there are common, systemic issue that drive this behaviour and it is decimating the female GP workforce.

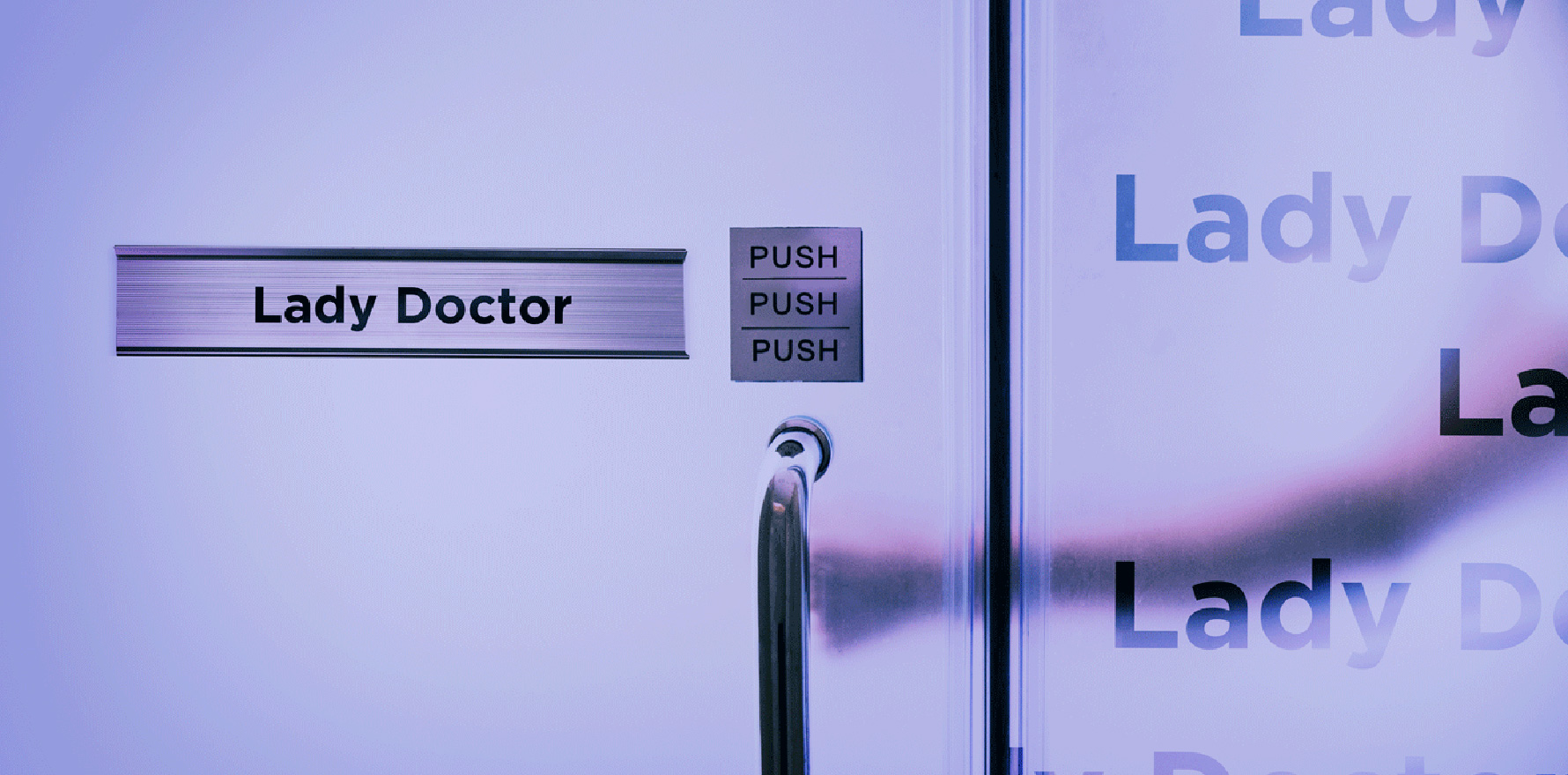

What is a ‘Lady Doctor’?

The term Lady Doctor is used to describe a bundle of stereotypes and assumptions about the nature of healthcare that genders our work. The Lady Doctor effect has been seen across time, disciplines and cultures. This part of our professional identity is usually not chosen, it tends to be imposed on us by the community, and by our medical colleagues.

As GPs, we are all expected to care for our patients, but the Lady Doctor is the one who is assumed to care as a vocation, a passion, something that she is both innately good at and finds intrinsically fulfilling. Gendered stereotypes of “feminine” and “masculine” skillsets feed the idea that women are the better choice if you need time and empathy because they enjoy that sort of thing. Lady Doctors also carry other gendered obligations in the community.

Lady Doctors are empathic, compassionate, understanding? and communicate well. They are also caring, generous and self-sacrificing. In general practice, this means they see more preventive care? and slow, complex, and emotionally intensive medicine. They also see less lucrative procedural medicine?, which explains the 30% pay gap. The devaluing of “women’s work” in general practice is reflected in the MBS, where patients are financially penalised for having complex problems.

Patients with mental health issues are more likely to be disadvantaged. There is also an expectation that this sort of caring work is “vocational” so patients and families feel an implicit permission to ask for more time, while lower fees, time pressure and patient self-selection excludes female GPs from doing more highly-reimbursed (“male GP”) work. This has a cumulative effect to devalue female GPs’ time and labour, and contributes to the disproportionate financial and emotional burden of Lady Doctor work.

Managing the Lady Doctor problem

- Individual responses

The wellness industry makes a fortune telling Lady Doctors they are the problem because they lack resilience. Everyone talks about resilience being about the ability to bounce back after adversity. However, the ability of a ball to bounce is a function of the ball and the surface on which it is required to bounce. Even a superball can’t bounce in a swamp.

It is critical that we understand where individual and systemic responsibilities lie so we stop blaming the individual for a systemic problem.

Lady Doctors often cope by creating portfolio careers, doing part time clinical work and part time education, policy or niche GP work, like breast health, lactation consultancy or dermatology. Anything with a salary offsets the financial cost of practice. This reduces access to mental health services for the community, but enables female GPs to survive.

- Education and training

The MBS defines the skills the federal government thinks are important for mental health care: depression, anxiety and eating disorder assessment and treatment with focused psychological strategies. This is an oversimplification of a GP’s job. The myth that we merely need to get better at diagnosing simple mental health issues and delivering evidence-based techniques is harmful, because these skills are insufficient to meet the needs of our increasingly complex patients. The GP curriculum is vast, and it’s inevitable that some areas of clinical practice will be covered in insufficient depth prior to fellowship.

Young Lady Doctors need to be supported with ongoing education, supervision and mentoring that is affordable and relevant if they are to continue to provide mental health services to their communities.

- Interventions at the practice level

Some practices have created innovative solutions to the problem of sustainability. They may share the clinical, emotional and financial load intentionally or outsource some of the Lady Doctor work to other health professionals. However, many practices are happy to direct the low paid complex work to the most junior members of the team because it is financially lucrative, and emotionally easier to do so.

Until the MBS and practice managers decide that one minute of complex mental health care is worth the same as one minute of work removing an ingrown toenail, Lady Doctors will continue to be penalised for accepting complex patients.

- Systemic change

There are broader systemic issues. We are holding more complexity in our communities, because our hospital systems are overloaded. We carry the emotional load of worrying about patients we know well, when we cannot get them the care they need. When I know one of my young, complex, homeless, traumatised patients may have temporal lobe epilepsy I should be able to access a psychiatrist without having to penetrate multiple layers of gatekeeping.

We also to need to get prevent the pinball experience. There is a lot of unpaid labour when our patients bounce around the system. Every triage without treatment is costly. To the patient, in time and trauma. And to us in unpaid care coordination work.

If we are to retain mental health capacity in our communities, we need to stop assuming we can milk the compassion of Lady Doctors through the holes in our policies. We need change on individual, practice and broader system levels, or the mental health capacity in our communities will continue to drain away.

Dr Louise Stone is a GP practising in Canberra and an Associate Professor at the Social Foundations of Medicine Unit at ANU Medical School; she tweets @GPswampwarrior. This piece is adapted from a presentation at the RANZCP 2022 Congress.

Jeremy Knibbs is on leave.