This doctor will always love general practice, but right now she needs a saner working life.

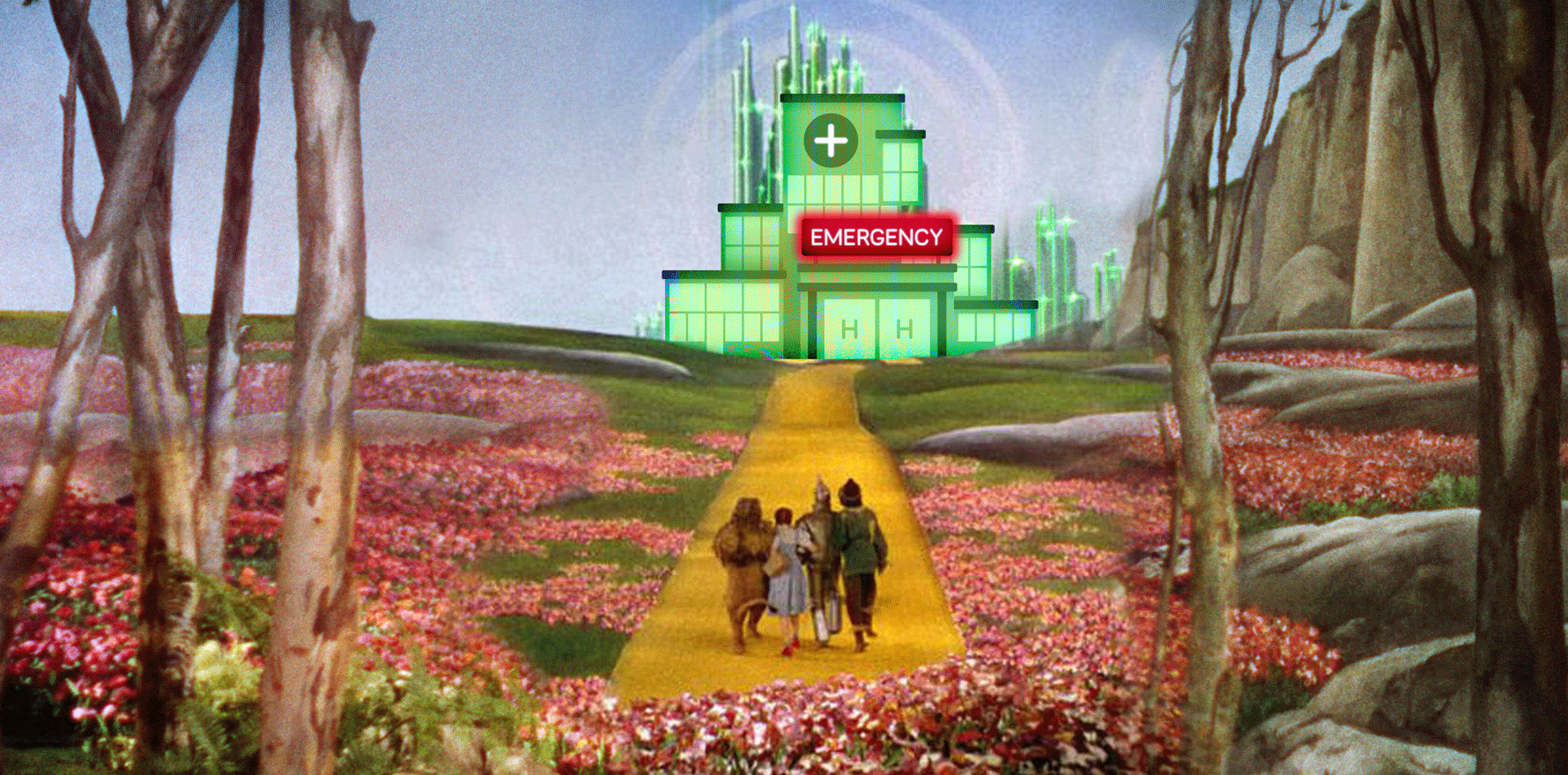

It is no secret that general practice is in crisis, imploding before our very eyes.

Many of my colleagues are speaking about closing their clinics and seeking greener pastures, whether that is retraining, finding stable jobs with hourly wages as employees or, of course, taking a break due to significant burnout.

I was told last week, twice, to consider stopping my passionate advocacy for general practice, and to take care of myself and do what I know works without worrying about anyone else. I admit, I am almost there, and it is not in my nature to quit.

I resigned recently from the private billing practice I began at only in August, for a multitude of reasons, among them, the fact that general practice IS imploding. I was waking up with a sense of dread before each shift and wondering what the day held. When I arrived, my day was mostly good, with grateful patients and staff, but every time a new-to-me patient entered my room I was anticipating the question of “Can you please bulk bill … ?”

Some months ago I put feelers out for locums in emergency to see what else is out there, and a few weeks ago, I did my first week.

I was flown out to a rural town in NSW for several days, having recently refreshed my emergency skills knowledge with an ALS2, with the only caveat that I didn’t want to be left on my own, nor be in a small enough hospital that I’d have to do airways or nights, initially at least.

I worked eight- and 10-hour shifts. They were busy with no formal unpaid breaks taken. I saw some presentations we’d not normally see in metropolitan general practice and a lot of things we would and do. I had many opportunities to brush up on my acute X-ray skills and my acute orthopaedic management for fractures and cannulate some kids that needed admission, which was initially nerve-racking.

The things that most struck me:

- I was paid an hourly wage irrespective of whether I saw one patient (if it was quiet) or 20 (if it was busy)

- Patients with lower acuity waited hours to be seen – some waited up to six hours for a Cat 4/5 presentation that could’ve easily been managed by a GP

- Despite this they were uncharacteristically grateful to be seen, even for literally five minutes, and sent home with reassurance; not ONE person got angry or upset with me

- Some presented with GP stuff, daily, including for followup, and when I asked if they had a GP, said “Oh we don’t need one”

- I sutured some single-layer lacerations and asked why they’d not gone to their GP: “I didn’t know my GP could do this”

What kept going through my mind, through my shifts, was the fact that for each of those presentations, taxpayers were paying $500 or more, including the ones returning daily for followup for minor presentations. The next thought that followed of course was “the government could double, or even triple every single person’s Medicare rebate and still save money on all Cat 4/5 presentations to ED, so why don’t they?”

Related to that, despite being busy every single shift, I never once felt frantic, or alone. I had people right there for second opinions, to look at X-rays with me, or agree with my management plans for areas I wanted reassurance on. Because I was not the only one rostered on to see all these people, I could work at my own pace, and see waiting patients as I was able. Not one person asked me to bulk bill them, nor did the discussion of money come up, because my wage was secure irrespective of their willingness and ability to pay.

In view of the significant burnout and disillusionment many of us currently face, I have decided I will be doing this work for the foreseeable future. It’s a no-brainer for the time being, if the alternative is to leave medicine. As a self-employed person, despite having been a doctor for 21 years, I do not have the luxury of paid long service leave or similar, so despite burnout similar to many other healthcare workers, bills need to be paid.

But as more locums are being lined up and I’m fielding weekly calls from agents keen to offer me to more hospitals for upcoming opportunities, I’m aware of a profound sadness. This ED work is important and it pays the bills, and it is giving back to the rural and regional communities who are struggling for doctors – but at the same time, the more of this kind of work I do, the more I realise how intrinsically built I am for the speciality that is general practice.

General practice is the speciality that is built on longterm therapeutic relationships. Where the therapeutic listening is just as important as prescribing a medication, or suturing a laceration. The speciality that enables us to see someone different with an undifferentiated problem every 15 minutes, and switch gears many many times in a given day.

It is the speciality that enables us to care for a woman in her pregnancy and then meet a new baby and help with her postnatal check and her baby’s newborn check. The speciality that enables us to screen for and treat postnatal depression, and discuss contraception, or sexual mismatch related to these things.

It is the speciality where, when a patient presents for “just a script, doctor, this is an easy one for you!”, we can opportunistically check when their last blood work was, or pap smear, or blood pressure check.

I could go on – but we all know who do this day to day, when we are thriving, how exhilarating it can be.

We are not just their specialist in life but if we are lucky, for life. Till we retire or they move on.

We are the speciality that signs on to witness all of it, the good, the bad and the ugly, to see someone for who they really are and to help them stay well, or to get better, or to hold space for them if there won’t be a better.

There is none of that in ED, nor indeed in almost any other speciality I can think of. There are stages of life where whole-person care is possible – e.g. paediatrics or geriatrics or obstetrics and gynaecology – but few do this for extended periods of time, nor do they handle everything that might come up.

My non-GP specialist colleagues, some of whom began in general practice and left, tell me they found it incredibly daunting not knowing what problem might walk through the door. It takes a generalist to deal with it and to triage for the non-generalist when we need to refer.

Almost three years since the practice I was at closed due to covid, I still get occasional DMs on my social media from patients who used to see me, asking if I’ll be back in the area, or telling me it was lovely to see me online – “you were my GP”. Some have found me and travelled to see me.

As GPs we effect changes in the lives of people that are intangible, invisible and priceless. That is why, while ED locums are fun for now, and I’m learning and giving back and mostly happy, it is not my medical home, nor is it my chosen speciality. It is not like general practice is when it is flourishing and thriving.

So my most ardent wish, as I reflect on this, is that the government finds a way to reform Medicare so that general practice as a speciality is not decimated, to be relegated to other HCWs working within limited scopes of practice. Because no matter how much training you offer, no one else can offer holistic, whole-person care the way the speciality of general practice – when done well – can.

Dr Imaan Joshi is – at heart – a Sydney GP; she tweets @imaanjoshi.