The story of the safe-sex-promoting Indigenous superhero is stranger than fiction, but is also a tale of how to do public health right.

To date, Australia’s Indigenous community has seen no covid-19 deaths, and a rate of infection approximately six times lower than non-Indigenous Australians.

Given historically poor health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islanders, there were initial fears that the community could be at increased risk of the disease.

This, however, is not the first time that Indigenous Australians have avoided the worst from a disease outbreak expected to disproportionately affect them.

The story of the first Indigenous superhero reads like the script of a blockbuster, and involves a small group of Indigenous healthcare workers, some light copyright infringement and the AIDS epidemic.

When Professor Gracelyn Smallwood first heard of HIV, she feared the worst for her community.

As a Biri woman growing up in Townsville, Queensland throughout the 1950s and 60s – a place where more than 90% of people voted no in the 1967 referendum – she knew systemic racism could run deep.

Working as a registered nurse and midwife in remote communities gave her extra insight into the particular vulnerabilities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in regard to health.

When Professor Smallwood was selected to be part of a national committee on HIV management in 1987, she immediately spotted a problem.

The committee, chaired by powerful media figure Ita Buttrose, had developed a public ad campaign featuring a Grim Reaper literally bowling down a group of middle-class Australians.

“I took one look at it and thought – Aboriginal people are not going to relate to this, because it’ll be seen as a bad spirit, and we’re very much spiritual people,” Professor Smallwood tells The Medical Republic.

“And the second thing was the bowling alley – there were no bowling allies in the communities, the missions where our people were sent.”

Having long been a human rights activist and self-described “controversial” figure, Professor Smallwood wasted no time in making her concerns clear.

“I did explain that to the chair lady and the wonderful people all on the committee, who all had different expertise – there were epidemiologists, gay community representatives, Christians – and so they actually listened,” she says.

“They listened, but they didn’t take too much notice.”

She didn’t walk away completely empty-handed, though: health minister Dr Neal Blewett gave her a grant to co-create a HIV/AIDS education program with other Indigenous healthcare workers from across Queensland.

The budget for this program development? A whole $5000.

Ultimately, after Professor Smallwood campaigned to various organisations and state departments for more funding, the federal government also sent four consultants to Townsville to help coordinate the program.

“What we did, because money was tight and I had quite a large home and a nice swimming pool at the time, most of the health workers actually stayed with me,” Professor Smallwood says.

“The older ones stayed on the bed, and the others camped in the loungeroom on the floor with a pillow.”

To help inform their final product, the group took a bottom-up approach and consulted with a laundry list of stakeholders: old people, young people, gay people, straight people, Christians, non-Christians, a Catholic priest, a Pentecostal pastor, and a football coach.

At the time, there was significant stigma around discussing sex, especially with Indigenous Elders.

Condoms, for instance, were more commonly known as “Frenchies” – leading to an awkward exchange with an older Palm Island woman who when she heard “condoms” had thought they were talking about quandongs, a native fruit.

“She said, at the end of the workshop, ‘well, I’ve got lots of quandong fruit trees over there, in my yard, and they’re grown on Palm Island, so I’ll bring over some boxes and you make sure you give them to all those footballers and all the little gay boys’,” Professor Smallwood told TMR.

“I had to change my plan of attack and strategy after that, given that the target audience was Aboriginal and Islander and there was that confusion about what condoms were.”

Talking to Indigenous Elders did, however, lead to a key revelation for the team.

“A lot of our people assembled outside the Commonwealth Bank, so we took the program to them,” Professor Smallwood says.

“We asked them what they thought, and a lot of the old people said that it’s really not for the audience of the Elders, but we support it.

“But get to those young ones – those teenagers who go to the All Blacks football carnivals, because after some alcohol everyone becomes Whitney Houston and Denzel Washington.”

This sparked the idea for a black role model to take centre-stage in a HIV prevention program – someone who could stand in hotels and drive-throughs promoting safe sex.

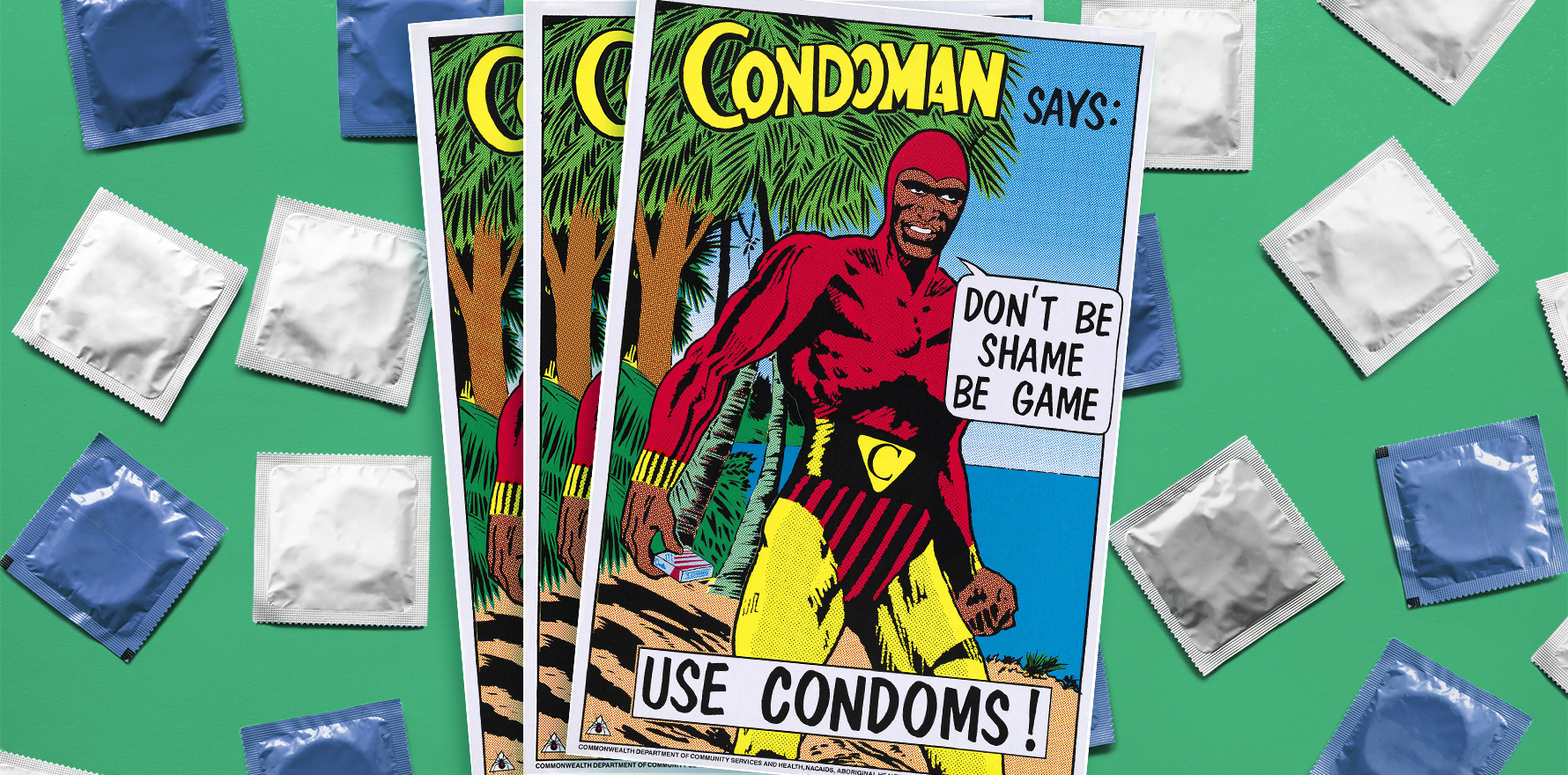

Enter Condoman.

Condoman came into the world when Ingrid Hoffmann, a graphic designer sent by the federal government, traced over an image in Lee Falk’s popular comic book The Phantom.

She gave him a different coloured outfit and black skin, but he was clearly recognisable as the popular superhero.

The idea was a hit.

Before long, Professor Smallwood’s mother had sewn a Condoman outfit. Now all they had to do was find someone to wear it.

“We had to pick a well-respected, beautiful, gorgeous black man who was very respectful to his partner, who didn’t have a reputation of hopping from bed to bed like a rabbit jumping from hole to hole,” she says.

“That was the most difficult thing, because it wasn’t easy for female partners to allow the male partner to dress up in leotards like the Phantom and call himself Condoman.”

She settled (with spousal approval) on Richard Blackman, a well-known schoolteacher and a football player on the James Cook University team.

With the help of Mr Blackman, Professor Smallwood and her team made an educational advert to introduce Condoman to the world.

“We filmed it at an All Blacks football Carnival, with a young black male and a young black woman [playing a couple] who were at the stage of experimenting with sex,” Professor Smallwood says.

“They went down to the bush area, and they were lying on a little mat under a lovely tree with the beach across the way, just about ready to make love and out of this tree jumped the Phantom man, but the black Phantom man, Richard Blackman – and he had a little box of condoms in his hand.

“He yelled out ‘don’t be shame, be game! Use Frenchies!’”

Unfortunately, in the process of jumping out of the tree Mr Blackman twisted his ankle and was unable to play for JCU in the semi-finals.

“People were not happy,” Professor Smallwood says.

“Can you imagine doing that today, playing for the Broncos or Cowboys?”

Professor Smallwood says her team were proud of the final package they put together, which was approved by Dr Blewitt and released just one month later.

They were heavily criticised by conservative politicians, Education Queensland and various church groups – “I copped a hell of a lot of flack” – but the Indigenous community embraced Condoman, thanks to her team approaching the issue from a grassroots level.

“A lot of non-Indigenous organisations were getting a lot of money for prevention, but we couldn’t see any value in their programs because they weren’t targeting their audience from a culturally appropriate perspective,” she says.

It was so successful, in fact, that Professor Smallwood was asked to present the project at a WHO event in London in January 1988.

“People were very interested, because I talked about poverty, and how if HIV got into these poor, poverty-stricken communities with poor social determinants of health, it will spread like wildfire, especially with high rates of other sexual transmitted diseases,” she says.

Just as Professor Smallwood’s Condoman initiative was starting to gain international success, with talk of it being adapted for use in some African countries, an unexpected obstacle was thrown her way.

“I presented on Condoman in America, and this lovely gentleman came up to me and said, ‘Where did you get the Condoman concept from, the design of the man?’” she says.

“Well, I said that because the Phantom was seen as a big hero and a nice, sexy white boy, we made our Condoman, and he’s a nice, sexy black boy, one of our big role models.

“And he said to me, ‘I’m one of the executives of Kings Comics’.

“And I said, ‘What’s Kings Comics?’”

Kings Comics owned the rights to the Phantom.

They were not pleased.

By a stroke of luck, all Condoman posters had recently been reprinted – where they once read “Product of Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers”, they now said “Product of the Commonwealth Department of Health”.

As a result, it was the government who had to field the incoming copyright infringement lawsuit from Kings Comics.

“I was told – and this is information that fell off the back of a bus – that the Attorney-General was given a letter from Kings Comics, and there was an out of court settlement for the copyright,” Professor Smallwood says.

In fact, the Kings Comics executive who first approached her had been so impressed that the company ultimately allowed them to keep Condoman so long as they tweaked the costume slightly.

Professor Smallwood’s advocacy work took her all over the world in later years, and she even presented on HIV in South Africa at the personal request of Nelson Mandela.

“He told me that in South Africa they’re having reconciliation with the truth, but in Australia we’re trying to reconcile without the truth, and it will never happen,” she says.

“But I’m optimistic that once truth telling is mandatory and justice is given – whether it be through health, corrections through deaths in custody or whatever – that justice will happen.

“Once that all comes together, and privileged white Australians understand that they’re up against 100,000 years of culture versus 230, with all that unresolved grief, loss and trauma, we’re on the road to reconciliation.”

Condoman remains an active figure in First Nations healthcare and was given a whole new look in 2009, along with a sidekick named Lubelicious.

By all accounts, it appears that Condoman worked; the rate of HIV infections in the Indigenous population remained similar to the non-Indigenous population right up until 2015.

Since 2015, the rate of new HIV infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has risen to approximately double the non-Indigenous rate, which has spurred the development of more culturally appropriate resources modelled on the Condoman success.

Dr Jason Agostino, a GP and medical advisor to the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, tells TMR that Condoman helped pave the way for successful covid-19 messaging.

“Humour runs through a lot of our communication messages – it was within Condoman, and for a lot of the covid-19 communication, it was about getting across important health messages with humour in them,” he says.

Crafting communications from a grassroots level, Dr Agostino says, helps create relevant information which increases engagement.

“We’re not very good at figuring out what it is that’s embedded within each community,” he says.

“But if that is your community where you live and work, you’re much better placed to think about what’s going to get through to the kids, what’s going to get through to the Elders and all the people in between.”

Although he isn’t Indigenous himself, Dr Agostino had a Condoman poster in his bedroom growing up.

“I got in trouble because I talked about it in class in grade four, and people thought that it was hypersexualised,” he says.

“Little did they know that I would turn into someone who works in public health.”

A Condoman poster now hangs in his workplace.